Homeschooling while homeless during coronavirus: 'Too many distractions going on'

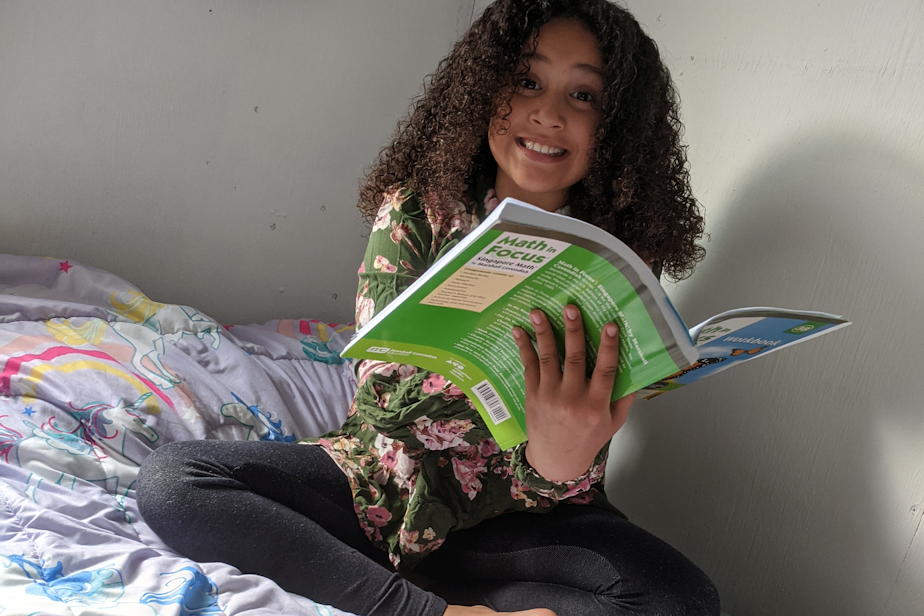

Eight-year-old Mariana Aceves does all her homework on her bed these days — because there’s nowhere else to be. The bed fills the entire tiny home she shares with her mom, Lorena.

The tiny home is the transitional housing the city of Seattle offered them until they get back on their feet.

“It’s enough room for a king-sized bed and a little tiny plastic dresser,” Lorena Aceves said. "And then we have another plastic shelving unit that we have our TV on top of, and then all of our clothing and our food goes underneath our bed.”

Kids all over Washington state are trying to get an education from home these days. For the about 40,000 of them who aren’t living in a permanent home, that’s even harder. Advocates worry these months about how remote learning could make it even more difficult for kids experiencing homelessness to keep up with their peers academically.

Aceves said she didn’t know her daughter’s school was closing till the night before it happened.

“Honestly, it was a complete panic attack for me,” she said.

Sponsored

Aceves had to quit her new job, because, with the school closed, she didn’t have access to child care during her work hours.

Now, she and her daughter are holed up in their tiny room.

“It’s the boredom,” Aceves said. “Her being in such high demand as far as attention and redirection and structure — it can be really difficult and frustrating.”

People who run shelters are mindful of the same issue.

Sponsored

“Families that we’re serving are experiencing trauma — housing crisis — and so the idea of also having to become teachers or support for teachers while dealing with that is a challenge,” said James Flynn, who works at Mary’s Place.

Mary’s Place has several family shelters in the Seattle area, with about 300 kids at the moment.

In some Mary’s Place shelters, each family has their own room, but in others, they’re just divided by curtains.

“I mean, the space alone is not set up for learning,” Flynn said. “The distractions of being in shelter around all kinds of other families and kids of many ages present a lot of challenges.”

Equipment is another challenge.

Sponsored

Some school districts, and some schools, provided tablets and mobile hotspots to all their kids who needed them. But many families experiencing homelessness still don’t have tablets or laptops — and, if they do, they may not have an internet connection.

“I can't really find a specific space where it’s like quiet and calm and I actually have wifi,” said 17-year-old Michelle Aguilar, a producer with KUOW’s RadioActive youth program.

Aguilar’s family is currently living doubled-up with another family.

That’s the most common form of homelessness: about three quarters of school-aged kids experiencing homelessness are sharing a house with another family.

Aguilar shares a room with her aunt behind the house. That room doesn’t have wifi, so she’s worried about being able to participate in her community college classes via video conference.

Sponsored

“If I were to do it in the living room or in the kitchen, everyone wouldn’t really care that I’m doing it — that I’m video-chatting with my professor or with my classmates,” she explained.

“They’d probably just continue their chaotic life of yelling and screaming and like playing music and listening to the TV and cooking,” she added.

All these obstacles add to the problems that children experiencing homelessness are already facing.

But Lorena Aceves is working hard to make sure her daughter’s education stays on track. She’s put together a strict schedule, with math, reading, typing, and built-in breaks every day — and she’s trying to find the silver lining.

“Even though this is frustrating, we are having this time together,” Aceves said. “And that’s something typically that we don’t have — because she goes to school in the morning and then she goes straight from there, straight to after-school care.”

Sponsored

Parents like Aceves may be getting some help soon.

The state has told schools to develop special plans to help students experiencing homelessness as long as the coronavirus outbreak keeps schools closed.