Diary of a maybe-coronavirus patient in Seattle who tried to get tested

Katherine is a 29-year-old Seattleite who is healthy but who picks up bugs easily. And now she wonders whether she has coronavirus, which is spreading in the region.

What follows is a timeline of events, from the moment Katherine may have been exposed to the virus, to finally getting tested – in the name of responsibility, more than wanting to know for herself.

We are not using Katherine’s last name because she does not want stigma attached to the small clinic where she works.

Wednesday, February 19

Katherine hangs out with a friend whose grandmother lives at Life Care Center in Kirkland. The nursing home will later be identified as the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak in the U.S.

At this point, as far as anyone knows, there has been just one person in the Seattle area with coronavirus – a man in his 30s who traveled to Wuhan, China, and who was isolated at a hospital in Everett while he recovered.

Sponsored

Unbeknownst to Katherine, someone from the nursing home is transferred out of the building on this day. That person would later test positive for COVID-19.

Also, Kirkland firefighters are starting to notice an unusual number of calls coming in from the Kirkland nursing home for respiratory distress and fever, both symptoms of coronavirus.

Saturday, February 22

Katherine feels sick. Still, she boards a plane at Sea-Tac Airport and flies to Sun Valley, Idaho, for a family ski trip.

“It was just a bad sore throat at first,” she says. “I thought maybe I had strep. I looked in my throat, but there were no white patches.”

Sponsored

She starts to cough. She is sweaty. The sore throat goes away, and she loses her voice almost entirely. Taking in a full breath is difficult.

“It’s not like I was deathly ill,” she says. “I went skiing. I felt like shit, and I was breathing way harder than I should be, and my family was laughing at me – you are too sick to be skiing. But I really wanted to be here.”

It’s flu season and Katherine, prone to getting sick, thinks, here we go again. The coronavirus doesn’t cross her mind.

Wednesday, February 26

Katherine flies home to SeaTac Airport.

Thursday, February 27

Katherine returns to work.

Friday, February 29

Katherine has friends over for a sleepover.

Monday, March 2

Katherine learns over the weekend that her friend’s grandmother is at the nursing home where there has been a coronavirus outbreak. Her friend’s grandma is sick, but not sick enough to warrant testing, per the CDC guidelines of that moment.

It isn’t until this Monday morning, back at work, still coughing hard, that Katherine gets a sinking feeling.

She calls her boss and says she will leave the building.

She goes to the department of health website, which tells her to call a COVID-19 hotline. She calls the hotline, and an automated recording tells her to check the website, and then hangs up on her.

Hoping for relief from her cough, Katherine downloads an app from University of Washington Medicine that will allow her a virtual doctor’s visit. She is prescribed a cough suppressant and an inhaler.

Sponsored

Katherine sees that the UW has instructions to call a community care nurse line, and she calls that number. Katherine feels she has a duty to report if she has coronavirus – although she has quarantined herself, she believes public health would want to know if she is infected. She has been so many places, after all, traveled to Idaho, spent time with her parents, who are in their 60s. Public health would want to track the virus, she reasons.

4:24 p.m.

A nurse named Pam calls to say the testing guidelines changed two hours earlier, and that Katherine can get tested – but needs a prescription from her doctor.

Katherine is baffled. Contacting her doctor means leaving a message in a web portal or with a call center. It’s not as simple as just making a call. She leaves a message through the UW web portal and gets two phone calls from people at UW, asking more questions about her exposure and symptoms.

Tuesday, March 3

Katherine wakes at 4 a.m., then 5 a.m., from coughing so hard. Her back and stomach are sore.

A nurse named Angela calls her from UW. She says the guidelines have changed again and that someone from Harborview Medical Center would text Katherine questions, and then decide, based on her answers, whether to go to her house to test her.

Harborview does not text.

4:40 p.m.

A nurse named Kara calls Katherine, asking if Harborview has been in touch.

“We want you to get tested,” Kara says, according to Katherine, who has started taking detailed notes of each interaction she has with a medical provider. “You can go to the medical center or Harborview ER.”

Katherine says she is closer to the University of Washington.

“I’m going to call in the test right now, and you’re going to go in right now and you’re going to get tested,” Kara says. Before they hang up, Kara says, “Tell them that Susan Kline wants this.”

Susan Kline is the director of nursing care and coordination for UW Medicine – Neighborhood Clinics.

5:40 p.m.

Katherine arrives at the University of Washington emergency room. People in the waiting room: “A lady with a terrible migraine, a guy with an injured leg, a guy with neck pain, three or four other people with masks and with coughs.”

She is checked in, given a bracelet, and swabbed. Someone puts a mask on her and returns her to the waiting room.

5:52 p.m.

Ping. An email lands in Katherine’s phone, telling her that she owes $206 for this emergency room visit, after insurance. The before-insurance cost is $1,643.

8:02 p.m.

The results are in. She is negative for the flu, A and B, and RSV. No mention of coronavirus.

9:15 p.m.

A nurse practitioner asks Katherine if her friend’s grandmother has tested positive. No, she hasn’t, Katherine says, because the grandma has not been hospitalized, and only those residents sent to EvergreenHealth community hospital in Kirkland are getting tested.

The nurse practitioner says that Katherine will not be tested, and that Katherine should not have come in.

Katherine reminds her that she was told to come in, and that someone named Susan Kline specifically wanted her to come in. The nurse practitioner replies, “We’ll have to work on that.”

“That’s when I was like, ‘They must have really limited test kits. Or they’re taking a different approach to this.’”

Katherine makes a mental note to call the billing department. “I can’t afford a $200 bill for four hours in the emergency room for a flu swab. They said, ‘We want you to get tested.’ I was instructed by UW employees to get tested. I did my due diligence.”

9:30 p.m.

Katherine receives her discharge papers from the emergency room and is told to leave.

Katherine texts her mom, who is 65, to check if she has symptoms. Her mother is fine. Katherine informs the people who slept over on Friday that she is sick, and that they can download an app to see a doctor via virtual visit.

“I’m Typhoid Mary,” Katherine said. “If I do have it, I spread it to Idaho. I was on a plane with multiple people, and god knows where they went. I was in two airports.”

Thursday, March 5

Katherine reports herself to the employee COVID-19 testing, fills out a survey. She receives a call within hours and is assigned an appointment to get tested at a drive-through site the next day.

Friday, March 6

1:30 p.m.

Katherine drives to an underground garage at Northwest Hospital in north Seattle. There are three white tents set up, with lab techs in head-to-toe protective gear.

“It’s very smooth, and they are clearly running a tight ship,” Katherine texts after her appointment in the parking garage.

They tell her results should be in 24 to 36 hours. She asks what test kits they are using because some of the kits have been shown to not work.

"COVID is 24 to 36 hours, I'm told," a lab worker named Jeff tells Katherine. Katherine has taken audio of the moment to make sure she gets the quotes right. "This is the first day we're doing it, so we'll see if that's true."

“They took different kinds of swabs than the ER,” Katherine says by text. “The ER took a nasal swab (inside my nostrils) and these swabs were nasopharyngeal, which (to my knowledge) is considered a superior specimen.”

She asks about the test, and Jeff replies that he is not a lab person, so he doesn't know exactly what test it is. "I just know that it's brand new," he says.

Jeff gives her a blue sheet of paper to show at the gate when she leaves.

“When you go to leave, don't roll down your window," Jeff says. "Just slap it up to the window and they'll let you out."

Katherine wonders if a test would be able to detect coronavirus given that 11 days have passed since the onset of her symptoms.

She knows the flu test works best when taken within three to four days of when symptoms begin. Same goes for the SARS, a coronavirus from 2003, for which positive tests showed up when samples were collected when there was viral genetic material in the specimen.

Katherine says this of the process so far:

“I definitely see an overall picture of how my communication has gone through four or five different channels, none of whom are communicating or able to communicate behind the scenes,” she writes by text.

“I can see that being a major challenge – how to collect and process what must be huge quantities of information both accurately and efficiently.”

Her insurance plan is entirely University of Washington based – an option for UW employees – which means that her doctor, emergency room, public health and employer are part of the same system. It would be even harder, she believes, for people whose care is spread across various medical systems.

“I imagine an organized efficient and accurate response is even more difficult as information and protocols continue to change,” she says.

Saturday, March 7

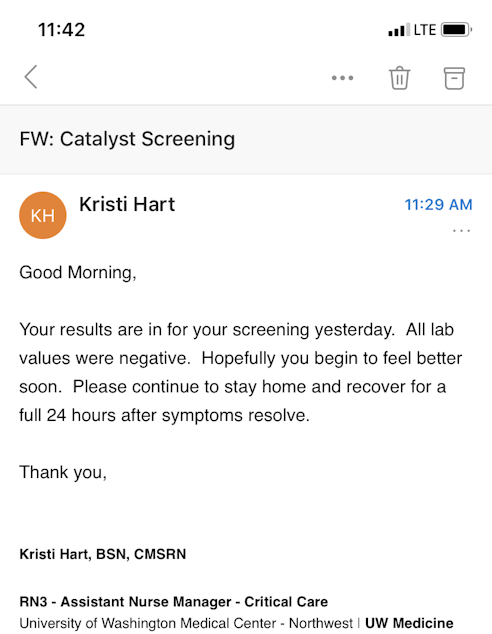

The results are in. Katherine tests negative for coronavirus.

"It's a big relief for me," Katherine says by text. "Not because I'm worried about myself -- I know I'm young and relatively healthy. But both my parents are over the age of 60 -- they're in the at-risk category. I have friends with chronic illnesses that make them at risk, and friends who are immuno-compromised. It's important to me that I am a responsible community member and neighbor and friend."

I muse that she could have also been disappointed -- because it is exciting to be part of a big story.

"We're all part of the big story," Katherine replies, "because we're all part of the human story, the global community."

Isolde Raftery is KUOW's online managing editor and can be reached at iraftery@kuow.org or via direct message on twitter @isolderaftery.