Dan Evans, three-term Washington governor, dies at age 98

Daniel J. Evans, former governor of Washington and U.S. Senator, died Friday at the age of 98.

In a statement given to The Seattle Times, sons Dan Jr., Mark and Bruce Evans wrote that their father lived an exceptionally full life. “Whether serving in public office, working to improve higher education, mentoring aspiring public servants … he just kept signing up for stuff right until the end. He touched a lot of lives. And he did this without sacrificing family”, the newspaper reported.

Before he got into politics, the Republican, three-term Washington governor and one-term U.S. Senator studied engineering at the University of Washington. And he cut his teeth helping design the old Alaskan Way Viaduct along the Seattle waterfront in the early 1950s.

Longtime Washington journalist and public TV host Enrique Cerna got to know former Washington governor Daniel J. Evans pretty well over the decades. He remembers him as a consummate politician. But with a practical twist.

“I think it was his engineering background that allowed him to accomplish all those things, but also to do so many things for the state of Washington,” Cerna said.

Evans was descended from a pioneer family. He became an Eagle Scout, and served in the Navy in World War II and Korea. But he never planned to be a politician. That all changed when he attended a precinct caucus, and got hooked. He ran for the state house in 1956 and won.

Sponsored

He was a Republican in a pretty Democratic state. But many old-timers, and not just politicos, remember Evans as an old school “State of Washington” Republican—meaning he was socially and fiscally moderate, but he also cared about the environment as a lifelong outdoorsman. As governor, Evans created the first statewide Department of Ecology in the United States.

Evans was also an executive also relished working with the legislative branch.

“I not only enjoyed being governor, but I enjoyed when the legislature was in session,” Evans told Seattle public TV station KCTS in 2014 “Most governors like to see them go away. But that’s what I loved. That was the time when you could get things done.”

Dan Evans was first elected governor in 1964. Soon after, he caught the eye of the national Republican Party. In 1968, the year that Richard Nixon was first elected president, Evans gave the keynote address at the Republican National Convention in Miami and made the cover of Time magazine. Later, in 1976, Evans was on the short list to become President Gerald Ford’s vice-presidential running mate.

Evans said he didn’t actively seek the VP job, but he clearly considered the “what if” of the experience.

Sponsored

“I think frankly that I could’ve been helpful in the election that occurred,” Evans said. “[Ford] finally selected Bob Dole as his running mate, and Dole turned into a very harsh and nasty debater in the election campaign and I’m not sure that that helped the president.”

When Dan Evans was governor, it was during an era of protests about civil rights and labor rights and against the Vietnam War. One particularly memorable visit to Pullman – for what was supposed to be a small gathering of campus Republicans at WSU – became something entirely different when 2,000 students showed up.

In 2022, Evans described to KIRO Newsradio how he scrapped the speech he had planned to give, and instead made the visit about asking questions of the thousands of students packed into a basketball arena, and then listening to their answers.

“’I don't want to tell you what we're doing, I want to hear from you what we should be doing,’” Evans said he told the students.

“And that started it off. And I was there for two hours, answering questions and getting really involved,” he continued. “It was one of the finest gatherings of any kind that I think happened while I was governor because they were intense, they were dismayed about what was happening in Vietnam.”

Sponsored

“They weren't particularly antagonistic toward me, but they just wanted me to tell them what I thought we should be doing, and then they had some ideas of their own,” Evans said. “So it was a great gathering.”

Some of the issues raised by the Vietnam War stayed with Evans for years. In the mid 1970s, when the United States was pulling out of Vietnam, Evans was a staunch supporter of refugees from that conflict. When then California Governor Jerry Brown spoke out against allowing refugees to settle in that state, Evans ordered then Secretary of State Ralph Munro to meet with military commanders to figure out how to move refugees out of Camp Pendleton in San Diego to Washington. Washington state ultimately welcomed in 500 Vietnamese people, then 2,000 more, and then 1,500 more.

In August 1967, Evans visited the Central Area, which was then Seattle’s predominantly Black neighborhood, for a public meeting and listening session for residents to speak directly to the governor. A few hours in, what had been a fairly humdrum event suddenly took a turn.

“One of the young guys sitting at the other end the table just put up his arm and pointed his forefinger at me with the thumb up and said, ‘Governor, if I had a gun right now, I'd shoot you,’” Evans told KIRO Newsradio in 2020. “And he pushed his thumb down as if the gun was going off.”

“I was silent for a few moments, and finally I said, ‘Well, what good would that do?’ [And] he said, ‘Well, [there’d be] one less honky to deal with.’” Evans continued. “And with that, the rest of them figured that they had overstayed their welcome.”

Sponsored

“’So I'll tell you what we'll do,’” Evans continued, coming up with a practical solution on the spot. “’We'll set up an office in the Central Area within 30 days, and we'll combine our forces so that it would be a one-stop place, I swear. You can come in and all of the services that are appropriate for the community will be in one place.’”

“And 30 days later, we opened,” Evans said.

That ability to adapt to a changing situation and make the most of it takes political instincts and skill, and Dan Evans told KIRO Newsradio he credits getting into politics as a 21-year-old college student fresh from military service – and the influence of, and example set by, his parents. His mom was gregarious and from a family with a long history in politics in Washington, while his dad was more low-key and quiet, and worked for decades as a civil engineer.

“I learned a lot from my father, who was an engineer and [who] ultimately ended up as King County Engineer,” Evans told the radio station. As King County Engineer, Dan Evans’ father Les Evans ran the road and other infrastructure-building part of King County government for 13 years.

“After I got back from service in World War II, I was finishing off the last two years of college at the University of Washington,” Evans continued. “I was in civil engineering, and I went with my father on occasion out to jobs that he was handling.”

Sponsored

Evans told KIRO Newsradio he observed his father patiently listening to ornery County Commissioners – when King County was run by a three-member board of commissioners – to hear about their desires to pave as many miles of roads as cheaply as possible. Their goal was to serve as many of their constituents as quickly as possible, and thereby increase each commissioner’s chances of re-election.

But Les Evans, his son Dan says, was successful in persuading the commissioners that building fewer miles of the right kinds of roads – more expensive, but longer lasting and made from concrete – was the right thing to do, if not the most politically expedient.

“I think I may have learned as much from him as I did from professors at the university,” Dan Evans said.

In his three terms as governor, one of Dan Evans’ biggest political regrets was not passing tax reform – which would have included a state income tax, but also reducing the sales tax and eliminating the B&O tax.

In 1983, Evans was appointed to fill the Senate seat vacated when Henry M. “Scoop” Jackson died. Evans beat Mike Lowry in a special election that fall to serve the remainder of Jackson’s term. But he didn’t enjoy his experience in the other Washington, and chose not to run for re-election.

“Many people have asked me, ‘Which did you prefer being more—governor or senator?,’” Evans once said. “No question. Being governor.

And part of being governor meant presiding over the festivities when the Eastern Washington city of Spokane hosted the 1974 World’s Fair. President Nixon was in the midst of the Watergate scandal and just months away from resigning, but he came to Spokane that spring for EXPO ‘74’s opening ceremonies.

Governor Evans and wife Nancy were there to welcome the beleaguered Commander-in-Chief at Fairchild Air Force Base. But Nixon must have had legal issues on his mind when he misspoke the name of the Chief Executive of the Evergreen State.

“President Nixon got up on the podium and I introduced him with, you know, the simple statement, ‘The President of the United States,’” Evans said. “And he turned to me in a very clear voice and said, ‘Thank you, Governor Evidence.’ Then he said, ‘I mean “Evans.”’ And of course, the press corps nationally who were there could hardly contain themselves.”

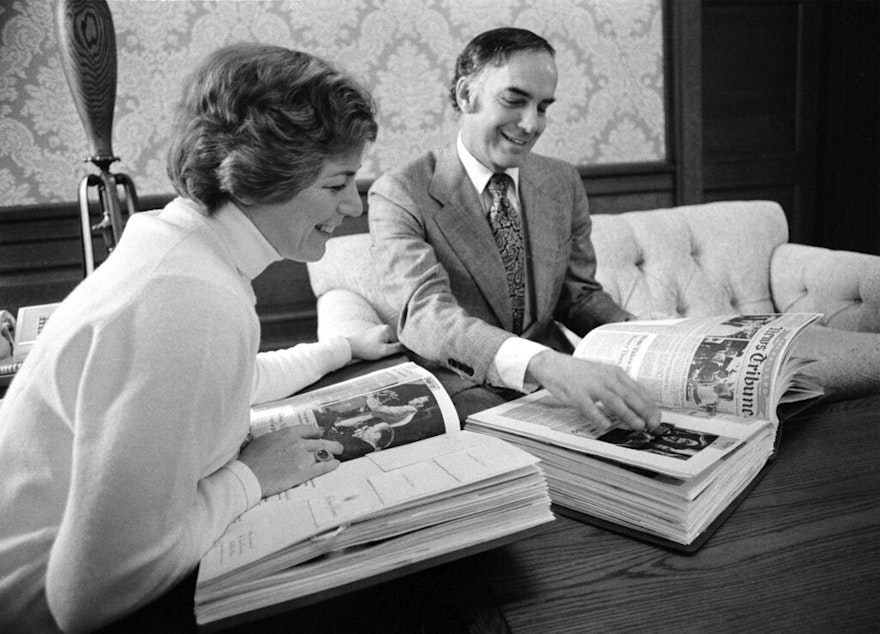

Evans spent many years working on his autobiography. “Daniel J. Evans: An Autobiography” was published in early 2022 by Legacy Washington, the history arm of the Washington Secretary of State’s office.

“I would have like to picked a sexier name than that,” Evans told KIRO Newsradio when the book was released. “I think I could have chosen one, but it's not the title that makes any difference, it's what's in it.”

Daniel J. Evans grew up in Seattle’s Laurelhurst neighborhood and lived there for much of the past several decades. The Public Affairs School at the University of Washington is named in his honor, as is the Daniel J. Evans Wilderness within Olympic National Park.

Not long after a ceremony at Hurricane Ridge for the official dedication of the wilderness area, Evans was out for a hike.

“I went around the corner on the trail and here's a big sign up there, saying ‘Entering the Daniel J. Evans Wilderness,’” Evans told KIRO Newsradio. “When you see your name on something while you're still alive — instead of a tombstone – that was pretty rewarding.”

Journalist Enrique Cerna says that along with places like the public affairs school and the wilderness area, it’s clear how Daniel J. Evans will be remembered in the Evergreen State.

“He was just one of those people that, because of his style of leadership, that it was easy to support him because he wanted to get things done,” Cerna said. “And that was really his legacy.”