Covid-19 immunity permits for Washingtonians? 'We're not quite there'

As the Covid-19 death toll rises, scientists are racing to understand the human body's response to the disease.

While some coronavirus antibody tests have been approved for use in the U.S., several key questions remain: What happens to the immune system after a person recovers from the virus? Could they be reinfected, and are they still a risk to others?

The Trump administration and some European countries have proposed allowing nonessential employees to return to work if they can prove they're no longer capable of spreading the virus.

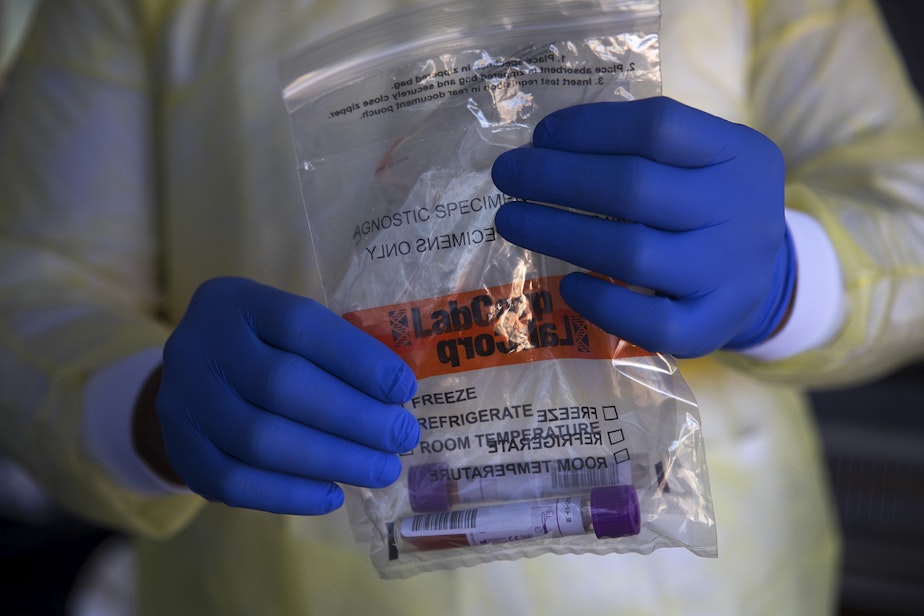

This would be done by testing for coronavirus antibodies, the proteins created by the immune system in response to the presence of a virus. U.S. officials said last week that coronavirus antibody tests would soon hit the national market.

As of April 15, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has authorized three coronavirus antibody tests. But some scientists argue that not enough is presently known about how novel coronavirus antibodies work, in order to correctly determine whether someone is immune.

"It's very likely that there are a large number of people out there that have been infected have been asymptomatic and did not know they were infected," said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases during an April 10 appearance on CNN's New Day. Fauci is also a member of the federal coronavirus task force.

"If their antibody test is positive, one can formulate kind of strategies about whether or not they would be at risk or vulnerable to getting reinfected, this will be important for healthcare workers for first line fighters — those kinds of people," he said. But those tests need to be validated, he added.

Fauci also stated that the prospect of people receiving immunity permits "is something that's being discussed" and that such a policy "might actually have some merit under certain circumstances."

Sponsored

But before the feasibility of such a policy can be weighed, the research must first catch up, said Dr. Helen Chu with the University of Washington's epidemiology department.

"We do think that having immunity to the virus may be protective," Chu told KUOW's The Record. "We don't know what an antibody test, at this point, means though. People who are currently infected and then recover from the virus — we don't actually know what the immune signature of recovery is."

Chu said it's not clear which particular antibodies could protect a person against Covid-19.

Researchers also have yet to discover how high those antibody levels would need to be to provide immunity, or how long they would last, she said. Moreover, having antibodies for the novel coronavirus wouldn't necessarily mean a person isn't still infectious to others.

Sponsored

"The idea of being able to have a test to say that you're protected and you can go back and work — we're not quite there yet," she said.

While there's still a great deal of uncertainty surrounding the immune system's response to Covid-19, Chu said seasonal flu epidemics could offer a window of insight.

"Once you get infected [with influenza] and you develop a protective response, that doesn't last for very long," she said. "And by the next year, you're going to be reinfected again or you're going to get another vaccine and that'll protect you for a certain amount of time but then you become susceptible again. And we don't know how coronavirus behaves."

The University of Washington's Clinical Immunology Laboratory has set out to help answer some of the looming questions about coronavirus antibodies.

"Basically, we're looking for antibodies that bind to the coronavirus proteins," said Dr. Susan Fink, assistant director of the University of Washington's Clinical Immunology Laboratory.

Sponsored

Thus far, the tests conducted by Fink's team have yielded varying outcomes.

"We've looked at a number of different assays, basically to look for performance characteristics — are they sensitive, are they specific? And one of the things that we found is that [with] the different sort of ways that you can measure antibodies, we get very different results," she said.

Samples collected prior to the pandemic have provided some insight, albeit inconclusive, Fink said. Her team is still trying to figure out the best method for measuring coronavirus antibodies.

"We see reactivity and the way we're interpreting that is we think that those are probably false positives," Fink said, adding that her team attributes this to the presence of antibodies for other coronavirus strains — not the one at the center of our current pandemic.

The Clinical Immunology Laboratory is also probing the potential for herd immunity against Covid-19: The concept of vaccinating a high percentage of people in a community to prevent them from contracting or transmitting an infectious disease, thus suppressing it.

"If we can develop an assay that we know is pretty specific for the novel coronavirus, as opposed to other coronaviruses that people have been infected with, then we can start to ask the questions about, 'Well how many people have actually developed these antibodies?'"

Sponsored

However, Fink said a lot more research is needed before drawing any conclusions about who might be immune to the virus.

The University of Washington's Virology Lab on Friday announced that it will begin performing widespread antibody tests starting early next week. The tests are manufactured by the Illinois-based health care company Abbott Laboratories, Inc. and people will be able to get them through their health care provider.

Read more about the new antibody tests here.

Bill Radke contributed to this report. Additionally, this report was updated on Friday, April 17 to include new information about antibody tests that will be available to Washingtonians in the coming week.