Too white? A criticism of Seattle Public Schools gifted programs for decades

The disproportionate percentage of white students in gifted programs has become a hot topic in Seattle in recent years.

But historical documents in the school district archives show that this debate goes back generations in Seattle.

Seattle Public Schools is currently grappling with how best to diversify its gifted program.

Children in the Highly Capable Cohort learn mostly, or entirely, in separate classes — and often in separate schools — from their general education peers.

The program was originally meant to serve elementary and middle school students in the top 1 percent by ability districtwide. Today, HCC serves 9 percent of white students and 7 percent of Asian students in grades 1-8.

Just 1 percent of black students and 3 percent of Latino students in elementary and middle school are in the program.

Superintendent Denise Juneau now proposes dismantling the HCC program and serving most students who would currently qualify for it in their neighborhood schools, instead, in general education classrooms.

“It is very [racially] disproportionate,” Juneau said in a recent KUOW interview.

“It is almost a segregated system,” she said, adding that it’s time to make it more equitable so more students of color can access these programs.

We pored over memos, charts and reports from past decades to see how these past strategies might help inform the district’s next one. Here’s what we learned.

Sponsored

1950s: The Space Race spurs the first gifted programs

There was a time when students who performed ahead of grade level often skipped one or more grades.

But by the 1950s, a growing body of research promoted a different model: keeping advanced learners with students their same age, and tailoring the curriculum to meet their needs.

Psychologists and education researchers found that approach often provided a more developmentally-appropriate environment than placing students with older children.

In the late 1950s came another big driver for gifted education in the United States: the launch of Sputnik sparked concerns that Soviet technology was outpacing that of the United States.

Sponsored

The resulting National Defense Education Act of 1958 provided funding to identify gifted students, among other efforts to boost the next generation’s math, science and foreign language skills.

1960s: Seattle introduces gifted education

Three years later, the Seattle School Board adopted a “Policy for the Education of Able Learners” which said the district has the responsibility to provide educational opportunities for every child that “will challenge his maximum ability” and “meet his individual needs.”

In 1963, the state legislature provided funding for gifted services. Seattle Public Schools used the money to introduce a new program, Accelerated Primary, “with the intent of providing for the individual needs of approximately 2.7% of the city’s able learners.”

Students selected for the program in first through third grade attended special classes at seven schools,then returned to their neighborhood schools in fourth grade.

Sponsored

Accelerated Primary was popular from day one, according to district records. “Parent interest was high and parents were most cooperative,” reads a report.

1970s: Race a factor in admissions

In 1975, the district set out to reinvent its initial gifted programs.

At the time, the district was several years into its first desegregation efforts: a small-scale busing program for middle school students.

A parent committee that was tasked with researching best practices in gifted education and issuing recommendations to the district insisted that desegregation could, and should, apply to gifted programs, too.

“When there is successful identification of all gifted children, grouping of gifted and talented students does not result in racially segregated classrooms,” the committee wrote in its 1975 report.

Critics of Seattle Public Schools’ current gifted services argue that basing qualification for HCC primarily on standardized test scores (qualifying students now typically score in the 95th percentile on district reading and math tests, and in the 98th percentile in two or more domains of an IQ test) discriminates against children of color and students still learning English.

They say standardized tests — often accused of being culturally biased toward white students — are an insufficient measure of children’s intellectual potential.

Nearly half a century ago, too, parents called on the district to use holistic measures of students’ abilities to create diverse and equitable gifted programs.

“The Parents’ Committee is concerned about over-dependence upon number scores” on standardized tests, parents wrote, citing research that showed limitations to “the appropriateness of the [IQ] test to the child’s language, socio-economic situation, and cultural background.”

“The District must begin an aggressive search for creative development of alternative testing instruments and identification methods for use with pupils of language and cultural minorities,” the committee wrote, pointing to the work of Ora Franklin, a black principal at Leschi Elementary School, who had successfully identified many children of color for that school’s gifted program.

If the district as a whole ever adopted alternative testing instruments or identification methods in order to achieve diversity in its gifted classes, we were unable to locate those records.

In 1978, the district’s busing program went full-scale. Students at all grade levels were bused across town, between the north and the south ends, to desegregate schools.

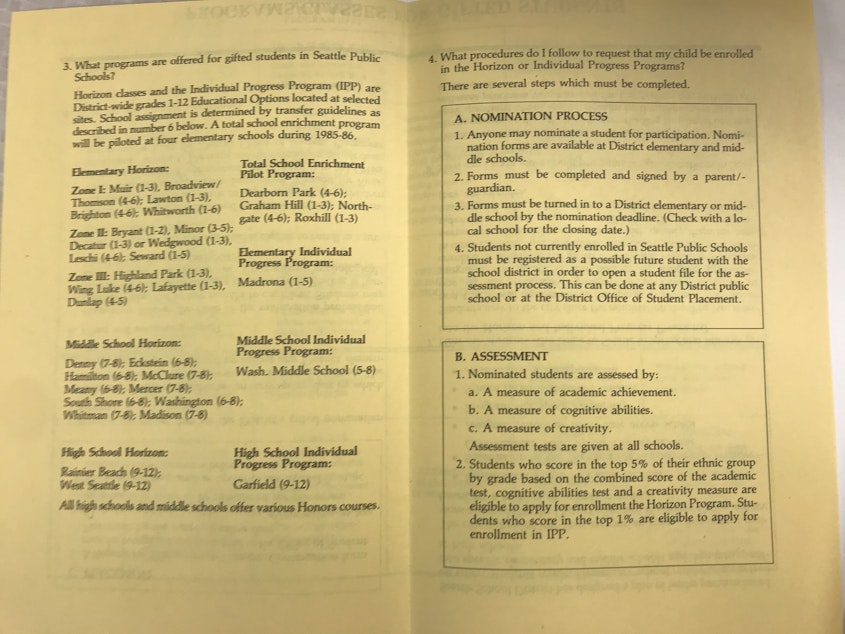

To make busing more appealing to white families, the district placed magnet programs — known as "option programs" — at schools that historically served predominantly students of color. One of those options was a new gifted program: Horizon. And for the first time, the district used race as a factor in admissions.

The program aimed to serve students in the top 5 percent of each racial group, as determined by IQ and achievement tests.

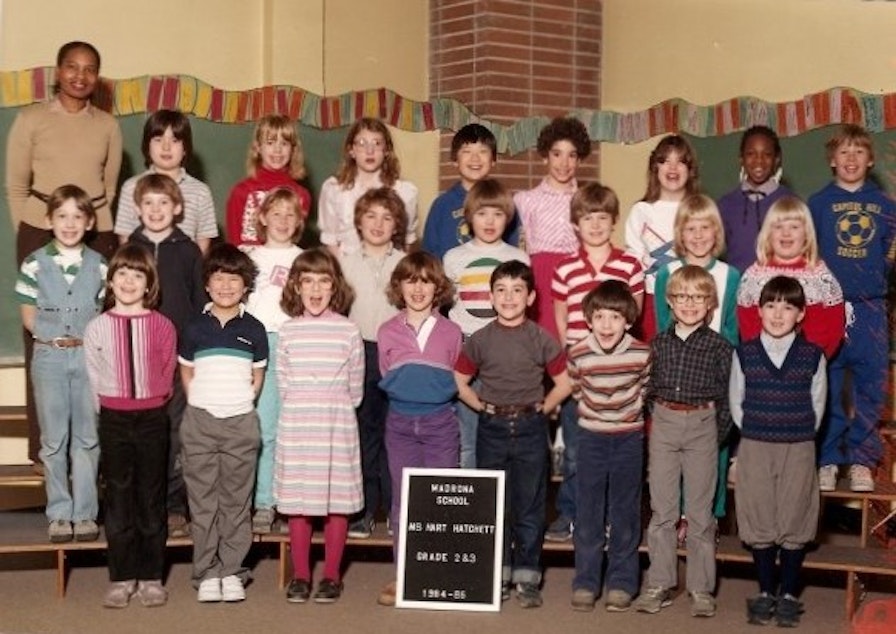

One year later, the district introduced the Individual Progress Program, or IPP, for students in the top 1 percent by racial or ethnic group on the same tests. (Full disclosure: I was in IPP in the 1980s and '90s.)

1980s: Racial imbalance draws criticism

The district said this affirmative action approach was important to adjust for test biases that would otherwise prevent highly-capable children of color from qualifying at a rate that legitimately reflected their abilities.

It was also a strategy meant to keep the new gifted programs in compliance with the school board’s mandate that option programs not stray too far from what was then termed the “majority/minority” balance in the school district.

By 1984, however, despite its stated strategy for desegregation, Horizon served primarily white children: the program had only 32 percent students of color, even though they made up 50 percent of the district.

A school district attorney at the time wrote that the system “favored parental persistence and time availability, permitted multiple retests,” and the results of student interviews, and that some schools were even admitting students to Horizon classes without the required screening. The attorney wrote that these practices “allowed the gifted programs to grow by reputation as ‘white programs.’”

Others in the district cited as factors the small percentage of teachers of color in Horizon classrooms, and called for better hiring and retention of staff of color — including school office personnel, who often provide the face for the school in working with parents.

To increase the percentage of students of color in Horizon, as well as in IPP, in 1984 the district strengthened testing protocols, started screening all students for possible gifted qualifications, and began doing gifted testing at school during the school day.

Within the first year of the change, the number of children of color enrolled in the district’s gifted programs jumped by 6 percentage points. But some white parents protested the changes, claiming they made it unfairly difficult for white students to qualify, and risked “dumbing down” the curriculum in order to accommodate less-qualified students of other races.

Shortly after the district rolled out its affirmative action model for the gifted programs, a white parent filed a complaint with the state, and a federal civil rights complaint, which launched an investigation by the U.S. Department of Education. The parent, a lawyer, then sued the district, charging unconstitutional discrimination.

The case was thrown out, and was in the appeals process when the state threatened to pull grant money for gifted services if Seattle continued its current model of taking only students’ test scores and race into account in determining gifted qualification. The state ordered the district to also factor in each student’s socioeconomic status, cultural background, and other environmental factors – not just race - if it wanted to continue to receive grants for gifted ed.

The district relented, and in 1987 once again reworked its system to identify advanced learners from diverse backgrounds. Not long afterward, the district phased out the Horizon program, eventually leaving IPP – later renamed the Accelerated Progress Program, and now called the Highly Capable Cohort – as the district’s sole gifted program in which children learn in separate classrooms.

2010s: Familiar problems - and familiar conflict

Today, HCC – a program created to serve a tiny subset of advanced learners, just 1 percent districtwide — has ballooned to include 7 percent of all students in grades 1-8. What has not changed in four decades: criticism that the district is over-identifying white students and under-identifying students of color, especially black children, for the gifted program.

What also has not changed is the search for a solution.

Superintendent Denise Juneau is now calling for the dismantling of the current system, arguing that most advanced students should be able to learn alongside their general education peers in their neighborhood schools. She has suggested that a small percentage of students working far ahead of their peers may still benefit from separate classes.

Many HCC supporters — most of them parents in the program — disagree. Some say the program would be much more diverse already if the district had followed through on many recommendations over the years to improve identification of highly capable students of color, such as by universal testing during the school day.

They question whether most teachers have the training and resources to teach students at vastly different ability levels. Many say their previous experience in neighborhood schools has shown them otherwise.

The current school board is divided on the issue, and has said the board will wait for the recommendations of a district task force, expected to come in the next few months, before making a decision.