Cheap At-Home Tests Could End The COVID-19 Pandemic By Christmas, One Researcher Says

The demand for testing is coinciding with coronavirus surges across the U.S, but the country isn’t keeping up. In many parts of the U.S., lines are long and test results can take days or weeks to come back.

The American Clinical Laboratory Association says it’s facing shortages of critical supplies. But what if there was an inexpensive, rapid test you could take at home a few times a week?

Well, epidemiologist Michael Mina says that's possible, and deploying the money and infrastructure for such a test could stop the pandemic by Christmas.

For at-home rapid antigen tests, a person would swab the front of their nose, Mina says. This is unlike the PCR test that uses a long swab called a nasopharyngeal to get deep in the nostril.

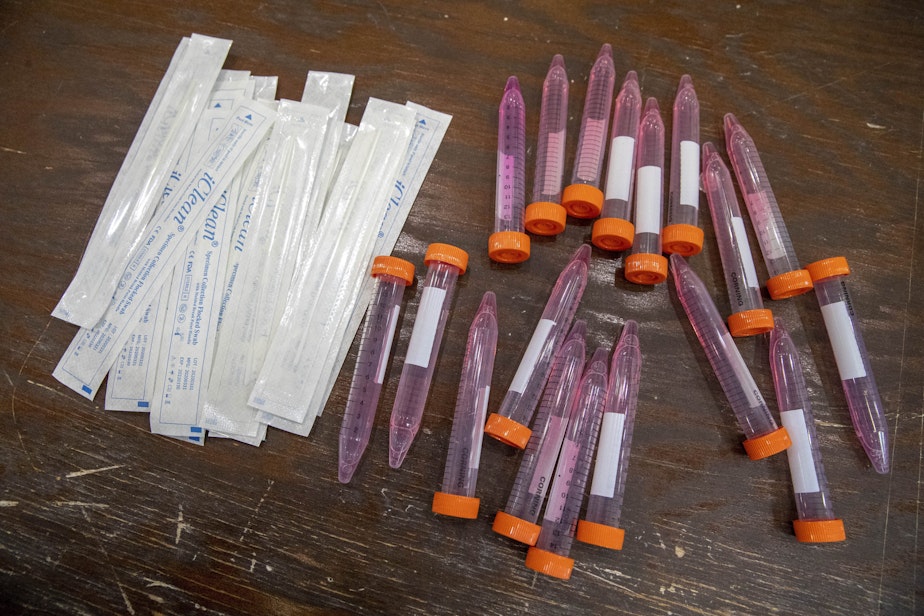

The test itself looks similar to a pregnancy test, he says. The nasal swab is placed in a small tube of liquid, he says, then a couple drops from the swab are put onto an encased piece of paper.

If a line on the paper strip appears, the test is positive. If no line shows up, the test is negative, he says.

Yielding a negative rapid test doesn't mean you don't have any trace of the coronavirus in your system, he says. What this test generally means is you're unlikely to be infectious at that point in time.

PCR tests are still considered the gold standard because they are "exquisitely sensitive to pick up the genetic material from this virus," potentially even weeks after a person has been infected, he says.

But PCR tests need to be sent away, meaning you could be infected as you await the results. Rapid antigen tests, he says, detect contagion right away, giving you real-time information on whether the coronavirus is live in your body.

"The antigen test, these simple paper strip tests, pick up the actual proteins of the virus and those parts will only be there when the person has live, likely contagious virus," he explains.

That way, Mina says you can know within minutes whether to quarantine immediately.

For the at-home tests, extra strips can be added as a backup against false positives. And if you're asymptomatic, the test can still detect if you have enough virus to likely transmit it to others, he says.

Mina argues that rapid antigen tests need to be considered as public health tools instead of medical devices, the category PCR tests are placed in.

Since rapid antigen tests are seen as clinical diagnostic tests by the Food and Drug Administration, at-home rapid testing has been difficult to roll out. Mina says he does want rapid testing to be regulated, but for each coronavirus test to be evaluated for a specific purpose.

"What I would like the FDA to do is to create a new pathway to regulate tools like these rapid antigen tests for the use that they should be intended for, [which] in this case is for public health mitigation strategies," he says.

Mina and other Harvard economists calculated the cost of starting a massive country-wide home testing program and determined it would have cost billions. However, they make the case that it would have saved a lot of money because it could have avoided lockdowns and saved lives.

"The U.S. government can produce and pay for a full nationwide rapid antigen testing program at a minute fraction (0.05% – 0.2%) of the cost that this virus is wreaking on our economy," Mina wrote in TIME.

The at-home system also relies on people to test themselves multiple times a week along with adhering to health safety measures such as mask-wearing and social distancing. Mina believes people would react well to an individualistic approach that "meets people where they're at" — such as letting folks test themselves in the comfort of their own home — compared to the current "top-down, more paternalistic approach" of COVID-19 testing.

"Unlike a mask which has become politicized in many ways, these tests take less than one minute to perform and you do that twice a week," he says. "And I believe very deeply that people, even the most ardent non-mask wearers, still recognize that this is a real virus and they don’t want to mistakenly give their 80-year-old parent coronavirus."

There has been some concern that folks would let their guard down if they used at-home testing on a regular basis and received consistent negative results. Mina says the same argument — that a safety measure would backfire — was used when seat belts and pregnancy tests were invented.

Mina perceives the pandemic as a "war" where businesses need to come together to make at-home testing possible. While it may be expensive, "$5 billion is not expensive for a war that’s literally cost us trillions," he says.

The tools and innovation to get rapid antigen testing into the homes of millions of Americans exist in the U.S., he says. He advises getting the country's technology companies on board and using the Defence Production Act to increase the speed of manufacturing tests.

"These should not even be questions if we actually consider how many Americans have died and what the economic and social toll has been on all of us," he says.

Karyn Miller-Medzon produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Chris Bentley. Serena McMahon adapted it for the web.

This article was originally published on WBUR.org. [Copyright 2020 NPR]