Family of Auburn man killed by police sues city, officer who shot him

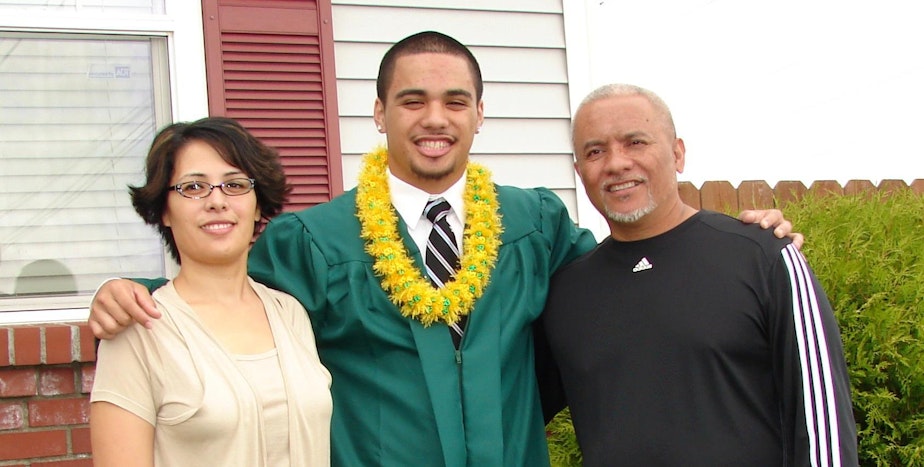

The parents of Enosa "EJ" Strickland Jr. filed a federal lawsuit Thursday against Auburn Police Officer Kenneth Lyman and the city of Auburn, Washington. They allege that Lyman’s negligence and unconstitutional excessive force resulted in their son’s death on May 20, 2019.

The lawsuit states that since joining the Auburn Police Department in 2016, Lyman has been the subject of at least a dozen use-of-force reviews.

“I’ve never seen anyone rack up this number of use-of-force investigations in such a short period of time,” said Ed Moore, the attorney for Strickland's parents, Enosa Strickland Sr. and Kathleen Keliikoa-Strickland.

Lyman was also disciplined for committing a hit-and-run with the department's SWAT van in 2020, according to an internal investigation and findings released by the police department. The victim of the collision has filed a lawsuit and obtained internal records that detail Lyman's disciplinary history.

The lawsuit and scrutiny of Lyman's record comes as the state's Criminal Justice Training Commission, the agency that oversees and certifies police officers in Washington, implements new rules to investigate citizen complaints and potentially revoke officers' certification, under legislation passed in 2021.

"A few weeks ago the CJTC adopted a policy that past misconduct and the patterns of an officer over time are all appropriate for an investigation by the CJTC, which would embrace this officer's history, including the death of Enosa Strickland," said Leslie Cushman with the Washington Coalition for Police Accountability, a reform advocacy group.

According to the complaint, Lyman and another officer were initially summoned to a domestic disturbance and found Strickland, 26, outside his ex-girlfriend’s home. Strickland had already called his parents, who were coming to get him. The officers were waiting with Strickland, who appeared intoxicated, when they said Strickland’s demeanor changed from friendly to physically aggressive, and Lyman tackled him to the ground, court documents say.

Sponsored

According to the lawsuit, which seeks unspecified damages, Lyman was carrying an unauthorized dagger, which became his justification for shooting Strickland. Lyman and the other responding officer, Derek Morse, told investigators they feared Strickland would gain control of the knife when it fell from Lyman's pocket during the struggle.

Strickland's ex-girlfriend said in an interview that she heard Lyman telling Strickland to "drop the knife," and Strickland respond, "What knife are you talking about?" Then she heard Lyman's gunshot.

Moore, the family's attorney, said Lyman’s knife is a major focus of their lawsuit.

Moore said Lyman's possession of the concealed dagger violated state law. He added, “It’s a knife that’s in violation of Auburn policy. It is the only justifying factor for E.J.’s death. And had it not been negligently brought to work that day by Officer Lyman, you would hope that EJ would still be alive today.”

The lawsuit claims that Lyman’s use of deadly force was grossly disproportionate and inspired by “malice or excess of zeal.” It said Strickland, who was unarmed, “posed no risk of serious harm or death to anyone.”

However, an outside review by Snohomish County Prosecutor Adam Cornell said that Lyman “had a good faith basis for using deadly force” against Strickland. Cornell said there were not grounds to prosecute the officer.

The family's lawsuit also alleges that the city of Auburn failed to adequately train, supervise and discipline its officers. A spokesperson for the city of Auburn said they are not commenting on the lawsuit at this time. As of Thursday, Moore said Lyman had not yet been served with the complaint, and the court file did not list an attorney for him. Attempts to contact him were unsuccessful.

The Auburn PD has not yet responded to a request for comment on this story, including whether Lyman has continued working or has been placed on administrative leave.

(Lyman's deadly encounter with Strickland came just eleven days before another Auburn police officer, Jeffrey Nelson, shot and killed Jesse Sarey. Nelson has been charged with second-degree murder in Sarey's death and his trial is expected to be the first test of the state's new wrongful death standard for police officers.)

Sponsored

LYMAN COMMITTED HIT AND RUN WITH SWAT VEHICLE IN 2020

Peter Manning was finishing up a day of hauling dirt in a borrowed box truck on May 15, 2020, when he heard lights and sirens and saw police vehicles coming up behind him through heavy traffic in Federal Way, Washington. Manning told KUOW there wasn’t room to pull over completely, and the next thing he knew, a van -- which was later found to be a SWAT vehicle from Auburn driven by Officer Lyman -- struck his truck and knocked its back mirror off.

Manning said the police van hit his bumper, flinging him and his nephew forward, and side-swiped his truck again before continuing on its way. Manning retrieved the broken mirror from the street and followed the police van, thinking it must have pulled over further ahead.

“We drove around the corner and they weren’t there,” Manning recalled. “I said, ‘They hit us pretty hard! They don’t stop?’”

Manning’s troubles didn’t end there. He called 911, but he said the dispatcher hung up, assuming his claim was a prank. He filed a police report in Federal Way, but he said police there declined to submit it. A spokesperson for Federal Way police said in an email, "The driver of the involved vehicle was referred to the Auburn Police Department."

Manning said the collision left him with a lasting shoulder injury that has harmed his ability to work, since he can no longer hang sheetrock. He said he has accrued tens of thousands of dollars in medical bills.

Sponsored

Manning next received a letter from a claims adjuster with the Washington Cities Insurance Authority that offered him $1,000 and said that if Manning pressed further, information about his sex life would become public as part of his medical records. Manning said the city has refused to recognize the ways he was harmed by the incident.

“I get the feeling that I’m the criminal. I’ve done something wrong. And it’s crazy!” he said.

Manning sued the police department in January 2022.

Meanwhile the city of Auburn paid the truck’s owner $1,100 to replace the mirror and straighten the truck’s rear bumper and bottom rail.

Lyman reported the collision later the same day, and documents from Auburn PD chronicle the resulting internal investigation. In an interview with Lyman, investigators asked him if he said anything to his colleague after striking Manning’s truck. According to the transcript obtained by Manning's attorneys, Lyman responded, “It was probably something like, ‘shit, I just hit that guy.’ I, I don’t remember specifically but that sounds like something I would say.”

Sponsored

Lyman told investigators he was certain he hadn't injured anyone. "And I made the decision to keep going, knowing I was going to self-report as soon as feasible.” Lyman said the driver “knows we’re the police, so he knows where to find us.”

Auburn Commander Sam Betz issued a written reprimand to Lyman in June, 2020, in which he wrote:

“It was shown that you made a poor decision when you recognized that the SWAT van had collided with the rear mirror of the box truck. You continued to drive to the SWAT incident without stopping, even for a moment, to provide any type of identifying information to the driver of the box truck. The SWAT van does not have any identifying marks on it that would enable a civilian to identify which police department to contact.”

The investigation findings say Lyman engaged in “actual misconduct,” including “violating any misdemeanor or felony statute,” as well as conduct unbecoming of a police officer and failure to operate a vehicle safely. Under Washington State law, a hit-and-run is grounds for a misdemeanor if the driver does not stop to provide their name, address, driver’s license number and insurance information. A hit-and-run resulting in injury is grounds for a class C felony.

The city of Auburn’s communications manager, Tiffany Lieu, responded to a question on behalf of the city attorney. Lieu said, “We are aware of the misdemeanor charge regarding the hit-and-run incident but have not received the referral” from the police department.

Cushman, of the Washington Coalition for Police Accountability group, said in a statement that Manning's "situation is not an anomaly and we believe that across the state there are other instances of criminal behavior swept under the rug."

She said her group is seeking rules that require the Criminal Justice Training Commission to refer any criminal investigation of an officer to a law enforcement agency other than the employing agency, and for mandatory reporting of criminal misconduct to prosecutors.

LYMAN WAS COUNSELED FOR THREE SEPARATE USE-OF-FORCE INCIDENTS IN 2018 MEETING

A summary from Auburn Police Sergeant James Nordenger, which was obtained by Peter Manning as part of his lawsuit, describes a counseling session with Lyman in April 2018 that referenced a variety of use-of-force incidents. The sergeant advised Lyman that he was going “hands-on” too quickly, using significant force like neck restraints without justification, and had repeatedly failed to warn people that they are under arrest or that he was about to use force against them. (The state legislature enacted a ban on neck restraints in 2021.)

Nordenger discussed a traffic stop on Feb. 20, 2018, in which officers presumed the driver was impaired. Nordenger said the man was “more likely than not going through a psychotic episode, and the force used by Lyman was outside of training.” Lyman punched and kneed the man to subdue him, according to internal documents. Nordenger told Lyman he went hands-on too quickly, and should instead have used his crisis intervention training, which emphasizes taking cover, slowing down and speaking clearly and calmly.

Next, the counseling session discussed Lyman’s use of a neck restraint to render an unruly, intoxicated man unconscious to prevent him from re-entering the Muckleshoot Casino in Auburn. Nordenger said Lyman failed to inform the man that he was under arrest or to warn him before using force. He noted that Lyman already had a “coaching tip” in his file about the need to tell suspects they are under arrest prior to using force.

Lastly, Nordenger discussed Lyman’s arrest of a man at the local library who was the subject of a felony warrant. Lyman said the man has a history of being uncooperative and defiant toward law enforcement. Nordenger noted that the man resisted arrest by pretending to be asleep. Lyman used a neck restraint to put the subject on the ground and render him unconscious. Nordenger said Lyman should have tried a lower level of force or “even better, waited for another officer to arrive to assist him.”