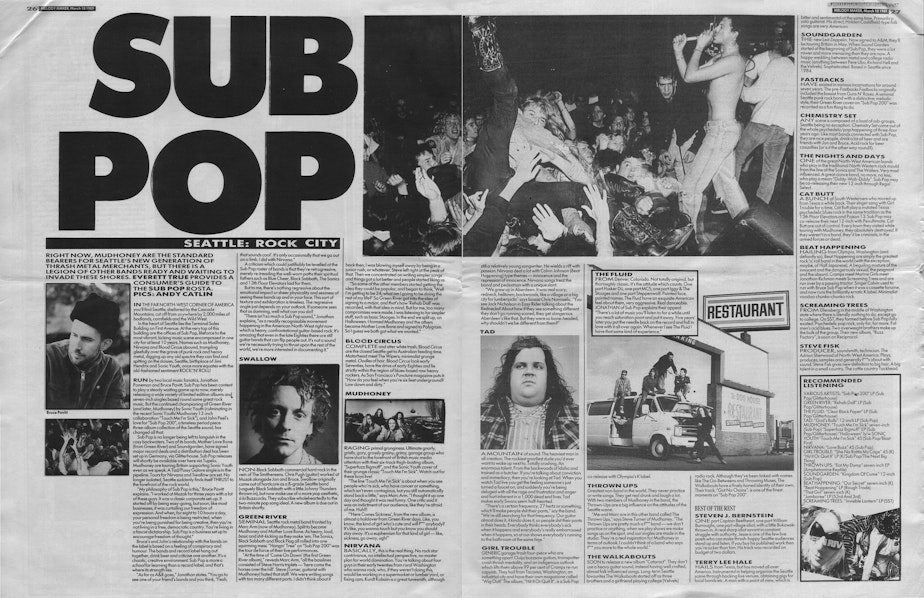

A tale of Sub Pop, the record label that put Seattle on the map

The sound of Seattle was shaped in part by a record label founded in 1988 called Sub Pop. Thirty years ago, that label was just a fanzine in Olympia called Subterranean Pop.

The founder, Bruce Pavitt, would review obscure independent rock recordings at Evergreen State College before he partnered with Jonathan Poneman as a DJ at the University of Washington's radio station, known then as KCMU (now called KEXP).

Seattle music writer Gillian Gaar was writing and reporting on Sub Pop and the Seattle music scene from the beginning. She talked with KUOW's Arts & Culture reporter Marcie Sillman about how the record label got on the map.

Marcie Sillman interviews Gillian Gaar about the history of Sub Pop on 'The Record.'

Interview highlights have been lightly edited for clarity

Gaar: The reason most people know Sub Pop now is because they signed Nirvana. They signed Soundgarden. They signed Green River, who split up and became Mudhoney, whom Sub Pop also signed.

Sponsored

So that gave them their first flush of fame.

Sillman: This is a company with the tongue in cheek motto: "Going Out Of Business Since 1988." There was a lot of truth to going out of business. It was a company that was born out of passion for music but also a lot of bravado.

Gaar: That was very much a part of their early days and actually even now. The thing about going out of business is that it's sort of the way the record industry works. You put a record out, distributors get it in the shops, and then people buy it.

The money eventually makes its way back to the distributor; the distributor has to pay the record company, and that could take a lot of time.

Sponsored

It's similar to being a freelancer — people aren't always as quick about giving the money back to you.

Sillman: So how did the Sub Pop founders manufacture hype and interest in Seattle?

Gaar: In some ways, that's a $64,000 question, because if you could give a definitive answer for that then every record company in the world would do the same thing. But it was a bit of happenstance and luck.

Sillman: You mentioned Nirvana and Mudhoney. Those are huge bands. But at the time that they were signed to Sub Pop, they were no-names, right?

Sponsored

Gaar: Yeah. They managed to get some coverage in the British press in 1989. They flew over journalist Everett True to cover what was going on in Seattle. He talked it up. At that point, most of those bands that he wrote about had barely even toured outside of Seattle, let alone outside of the state.

Sillman: A lot of these musicians were also working in the Sub Pop offices — the so-called "world headquarters."

Gaar: They weren't making a living from their music, so they definitely needed jobs. I guess the funny thing is that you could be working at Sub Pop, but that didn't mean your check wasn't going to bounce.

Sillman: Was there a point when Sub Pop really did teeter on that brink of non-existence?

Sponsored

Gaar: Well the first time was in in 1991, right before everything broke. It wasn't just the usual thing of bouncing some checks — they were bouncing about all their checks. They had no money left.

One of their distributors had declared bankruptcy, so they didn't get money there; they owed money to everybody, but they hardly had any at all. They laid off most of their staff and they printed up jokey T-shirts that read "What part of WE HAVE NO MONEY don't you understand?"

Sillman: What saved them?

Sponsored

Gaar: A couple of things. I think that hiring Rich Jensen to look over their accounts helped them. He didn't know anything about accounting. When he was offered the job, he said he went to the library and got a book and boned up on it. Jensen organized everything and set up payment plans so that they wouldn't be shut down.

Then they got two bonuses. Mudhoney had one more record to release before moving on to a major label, and they were considering not releasing it on Sub Pop because Sub Pop owed them money. But eventually Mudhoney agreed they would release it on Sub Pop, and that album, Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge, sold something like 20,000-30,000 copies — which was a good amount at the time for an indie record. That gave Sub Pop their first influx.

The second thing was Nirvana's Nevermind album; a percentage of the sales from that helped them, too.

Sillman: Sub Pop. Grunge. Seattle. They were synonymous, but Sub Pop Records was not a grunge label, and in fact, the company has released a wide span of genres. Was Sub Pop indelibly tied to a particular style, and if so, how did it transcend that identification?

Gaar: Pavitt and Poneman liked the bands first and foremost. The genre label came later. They had The Walkabouts on the label and he described them as "hippies with big amps."

They had Terry Lee Hale, a singer-songwriter type.

They released an early recording by Jesse Bernstein, the spoken word poet. It wasn't just grunge.

However, I always thought that "grunge" was a useful term because there was no clear way to describe this music, it was just a good catch phrase.

It bothered some people but it never bothered me, because before I used to call it "the music that could only be described with hyphens" because people would say "art-rock-noise-metal-punk" with a hyphen in between because it was this mishmash.

When you listen to Nirvana's Bleach, it isn't quite metal, but you can hear some metal in there, and it isn't really pop, but you can hear pop in there, and you can hear punk. So, what is this?

Sillman: How important is a record label at all, and Sub Pop specifically, today?

Gaar: Well there are all kinds of things that you can use a record label for. Because they're Sub Pop, and they have that name brand and people are going to be wondering what they're releasing, I think that gives them some influence.

They also handle all the business stuff. One way artists are making money on their music is by getting it into ads, movies, or things like that. You need someone to seek those out and know how to negotiate. A lot of musicians aren't going to be up for that, so that's where a label comes in.

Sillman: Who is on Sub Pop today that you're excited about?

Gaar: I'm glad Sleater-Kinney revived. They put out two albums since they came back — No Cities To Love and then the live album.

Sillman: For a person who's just moved here to work at a corporate behemoth in downtown Seattle, what's the most important thing for them to know about Sub Pop?

Gaar: Pavitt often stressed the importance of regionalism, so maybe that's what's most important. Pavitt found bands in the area, kept pushing them, and they all hung on against overwhelming odds. You can do it from where you are. You can make it yourself here. You don't have to go elsewhere.

Produced for the web by Brie Ripley.