Follow this Seattle scientist as he's injected for coronavirus vaccine project

Ian Haydon of Seattle is part of a project to develop an experimental coronavirus vaccine. He got his first injection on Wednesday morning.

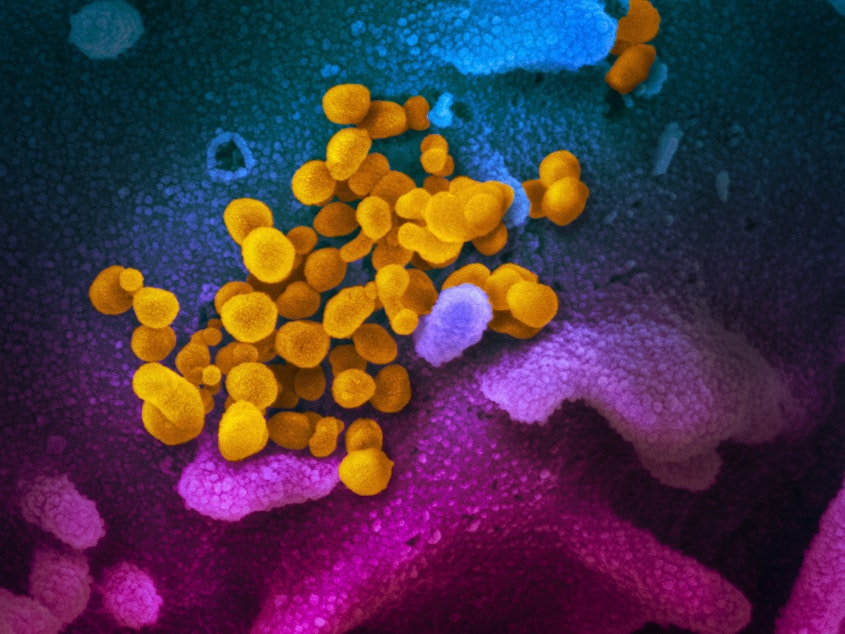

The vaccine is being developed by a Boston-based company called Moderna. It involves the use of a molecule called messenger RNA to try to prompt the body's immune system to fight the virus.

Haydon himself is a trained scientist and science writer. He works as a communication manager at the Institute for Protein Design at the University of Washington, which itself also develops vaccines.

“It's a little bit like getting ready to go on a big trip where, you know, you've been thinking about this thing and counting down the days and then all the sudden it's upon you,” Haydon said.

Typically, a vaccine works by injecting either an entire virus that’s been killed or a piece of a virus into a healthy person. The idea is for the immune system to recognize and respond to the disease by creating antibodies, proteins found in the blood that help fight bacteria, viruses, and other antigens.

But Moderna’s Covid-19 vaccine is much different.

“What I'll actually be receiving is a little snippet of the virus's genetic code,” Haydon said. “In this case, a single MRNA, molecule messenger RNA, and that genetic code is going to hopefully enter my cells and temporarily instruct them to make one of the proteins from the virus.”

The intention, he added, is for this immune system to react to the proteins by making antibodies that would be protective against the real virus.

The same MRNA technology is being used in clinical testing for other diseases, though the platform hasn’t yielded any licensed vaccines.

Haydon said the side effects currently associated with being injected with the experimental vaccine aren’t serious in the long run, but some have reported pain or redness at the injection site, and headaches. But, “those effects, which usually last just about a day, can be severe,” he added.

Additionally, it’s not exactly clear yet what impact the coronavirus — and therefore, the vaccine — have on the immune system.

“So in very rare cases, an experimental vaccine can actually make infection worse where your body does produce antibodies, but those make it easier for the virus to infect you rather than blocking infection,” Haydon said.

“So that's one of the things that clinical trials for any coronavirus vaccine are going to have to evaluate. And it's one of the reasons why you can't just rush a promising vaccine out of the laboratory and start giving it to a lot of people.”

Haydon is currently participating in the first phase of the study, which he said is merely the first step in a long process. It’s the later phases of the clinical trial that will yield more clear answers about the vaccine.

“It's not just safety that's being evaluated, but it's efficacy of the vaccine as well.”