A homeless man steals clothes from a Seattle Goodwill, goes to jail. His story isn’t unusual

Seattle charges people for stealing from Goodwill more than any other retailer. Almost one in three are homeless.

On a warm April day in 2017, a 47-year-old man walked into the University District Goodwill store and tried to walk out with a black sweatshirt, a gray shirt and a pair of sweatpants, totaling $29.97.

When the Goodwill loss prevention officer caught him and asked why he took the clothes, the man said he was homeless – he needed them. The clothes were returned to the store’s stock, but two months later, Seattle city prosecutors charged him with theft. There is a warrant out for his arrest.

Later that year, in November, another Goodwill loss prevention officer stopped a 23-year-old homeless mother with her young son outside Goodwill’s Central District store. The officer had watched her on the closed-circuit TV hiding items from the kids’ section in her purse – $62.

The officer filed a report with the Seattle police, and the Seattle City Attorney’s Office followed up with a theft charge. To dismiss it, she agreed to 20 hours of community service, to notify the court of any changes of address and to stay away from Goodwill.

A third homeless person, a 29-year-old man, was charged with theft for stealing $36.66 in merchandise from Goodwill — t-shirts, socks and headphones. He spent 19 days in jail.

Sponsored

These are three of the 318 people charged by Seattle prosecutors for stealing from Goodwill — one for as little as $13 worth of merchandise — in a single year. In that time, between November 14, 2017, and November 14, 2018, the City of Seattle prosecuted more people for stealing from Goodwill than any other retailer.

Counter to Goodwill’s mission to help low-income people find opportunity, an analysis of Seattle theft data also shows that Goodwill’s choice to pursue charges against people shoplifting for survival cycles many homeless people back into the criminal justice system: More than 29 percent of the people charged for stealing from Goodwill told security guards they were homeless or had a shelter listed as an address. More than half spent time in jail as a result.

There's also a racially disproportionate result: Almost 22 percent of Goodwill defendants are black, even though black Seattleites make up less than 7 percent of the city population.

In nearly every case, the items were returned to the store after the suspect was caught.

“Taxpayers basically subsidize Goodwill’s recovery of a $7 pair of socks that they already got back to the tune of several thousand dollars-worth of money spent on prosecutors and courts and jail,” said James Carr, a public defender in King County. “It's just absurd.”

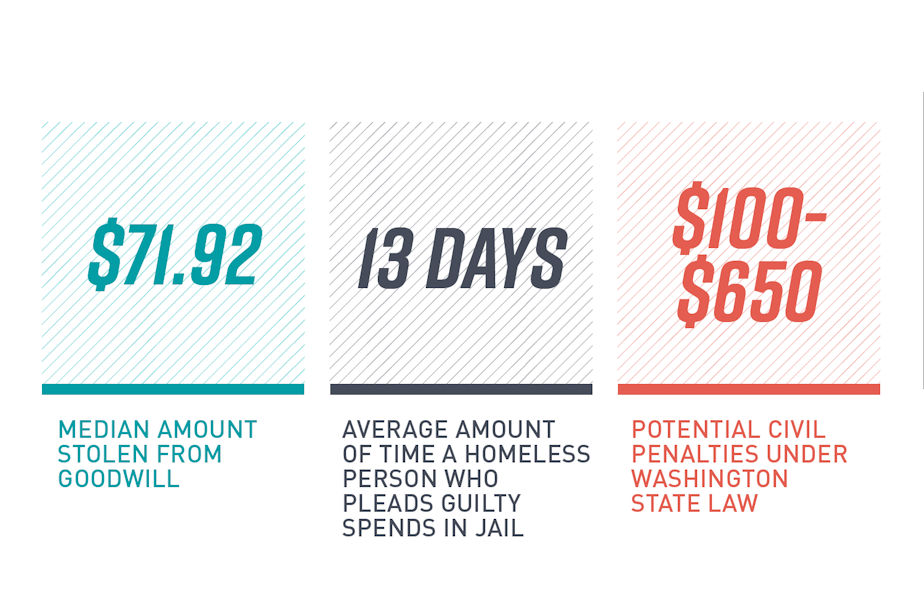

The lowest amount someone was prosecuted for in the data reviewed by KUOW was $13. However, while it's almost impossible to calculate how much the City of Seattle spends on these cases, Carr's estimate could be close: For homeless defendants who pleaded guilty to a Goodwill theft charge, the average time spent in jail was 13 days, costing the city roughly $2,585.62 on jail booking and daily maintenance alone.

A

ccording to Seattle Goodwill’s annual report, the nonprofit made more than $9.2 million in net proceeds from its thrift stores, and another $6.7 million from donors, grants and investments between 2017 and 2018. The organization spent more than $11.2 million on job training, basic education classes and services, and helped 1,720 people find jobs.

The report highlighted the success stories of several people who found employment through Goodwill. One of those stories described the struggles of a man named Lazon, who had a misdemeanor record that prevented him from finding work, became homeless and resorted to stealing to survive. After graduating from one of Goodwill’s free job training and education programs, he was hired at the Goodwill store in Redmond, Washington.

If Lazon had stolen from Goodwill, however, he would likely have ended up with a bench warrant. KUOW’s analysis of theft data shows that Goodwill theft charges net the highest number of homeless defendants than any other retailer in the city.

The Seattle City Attorney’s Office told KUOW it believes those numbers are an undercount. They don’t include homeless people who give old addresses, for example, meaning there may be even more people prosecuted for stealing donated goods.

Goodwill says its mission is to help people in need – and stealing from Goodwill means stealing from the job training programs that help other low-income people.

Sponsored

Seattle Goodwill spokesperson Katherine Boury told KUOW that 13 percent of its job training students struggle with homelessness. The organization spent $86,415 on housing for its students last year and an additional $76,794 on clothing.

As for pursuing criminal charges for low-level thefts, “The best practices in the retail industry indicate that complacency in dealing with shoplifters sends the wrong message to the community—that stealing is okay,” Boury said. “It also tells the community that we don’t value their donations or our regular customers.”

But Goodwill doesn’t stop at criminal prosecutions. The organization also retains a Florida law firm to send letters demanding money, often hundreds of dollars, from people accused of shoplifting. Amounts can range from $100 to $650 under Washington state’s anti-shoplifting law.

This tactic – legal in Washington state – can confuse some defendants in theft prosecution cases, public defender Marci Comeau said.

“They were given the impression that by paying the penalty they had resolved the case, kind of like if you pay a ticket you resolve your ticket or your infraction,” Comeau said. “It was kind of a double whammy.”

For people who can afford to pay off Goodwill, there is a way to drop charges: a “compromise of misdemeanor” motion from a defense lawyer. These motions allow a defendant to negotiate directly with Goodwill to drop charges, usually if that person paid or negotiated the civil penalty.

Seattle Goodwill told KUOW that it accepts these compromises once a week on average and “individually evaluate all requests for compromise.”

“Now obviously for people who can't pay that, that translates into them having a theft case,” public defender Elaine Saly said. “It just turns out to be discrimination based on ability to pay.”

City Attorney Pete Holmes said it would be worth asking why retailers pursue civil penalties on top of criminal charges. “It’s not necessary,” he said.

When asked this question, Seattle Goodwill’s Boury told KUOW by email that such civil recovery options are authorized under Washington state law. “All funds that we collect go to funding Goodwill’s job training and education programs,” she said.

Despite the option for compromise, jail is the most frequent outcome for homeless people after being prosecuted for theft from Goodwill. KUOW’s analysis showed that 58 percent of homeless people prosecuted for stealing from Goodwill ended up in jail, often before a trial or judgment.

“Generally speaking, people who [steal from] Goodwill probably don’t have the most stable living situation,” said Carr, the public defender.

For those people, the process then goes something like this: After a Goodwill loss prevention officer catches someone stealing, that officer files a report with Seattle police through the police department’s retail theft program. The City Attorney’s Office reviews the police report and decides whether to file a theft charge.

A court summons is then sent to the address that person provided. If the person doesn’t come to court, a warrant is issued for their arrest.

Pete Kurtz-Glovas, program manager for the Compass Housing Alliance, said his organization handles mail for more than 3,000 people.

“We try to work with clients around things like this, but we're pretty hamstrung by the amount of mail we receive,” Kurtz-Glovas said.

Compass holds onto mail from the Department of Social and Health Services for four weeks, and everything else for two weeks – with exceptions for photo IDs and paychecks. The organization receives a lot of court summons, Kurtz-Glovas said.

“If we get a standard envelope that says ‘King County Courthouse,’ we don’t screen it,” Kurtz-Glovas said. “There’s not enough space to hold onto it for too long. We’re interested in finding new ways we can help folks out.”

Carr, the public defender, said that some judges set high bail amounts for people who don’t respond to these summons or show up to court. When they’re arrested, they often don’t have the means to bail themselves out.

According to KUOW’s analysis of city theft cases, nearly 32 percent of people prosecuted by the city for stealing from Goodwill since November of 2017 have active warrants out for their arrest. Another 24 percent have pleaded guilty to the charges – sometimes, public defenders say, just to get out of jail.

Then, they’re left with another mark on their records that can further prevent them from finding employment and housing, perpetuating the cycle of homelessness.

“Part of the purpose of Goodwill is for job training,” public defender Chris Jackson told KUOW. “And yet when our clients end up with theft convictions, they’re the kind of people who can't get jobs.”

C

ity Attorney Pete Holmes said his office has an obligation to treat major retailers selling donated goods the same way prosecutors would treat mom-and-pop shops harmed by shoplifters: “We have victims, we have people who have been harmed, and they're entitled to our assistance,” Holmes said.

But Holmes recognizes that many of the Goodwill defendants are stealing for survival.

“What you see here is some behavior that is just begging for some kind of intervention, and in social services more likely than not,” he said.

“We don't have a policy that if you're homeless, you escape, you will not be held accountable,” Holmes continued. “I wish I could house them instead. But, legends to the contrary, we don't have a standing get-out-of-jail-free card for someone who's homeless and we couldn't.”

Holmes told KUOW that in order to address the root causes of shoplifting, you’d need social services, housing, treatment for chemical dependency – not the criminal justice system. He pointed to his office’s diversion program for 18- to 24-year-olds as one way his office is trying to achieve different outcomes: by diverting those cases before they're filed in court. No such program exists for older adults.

Holmes also said that his office has engaged with Goodwill over the issue of theft cases and homeless defendants in the past – he said he was reassured to find out that loss prevention officers can use their discretion over whether to pursue charges and sometimes give away items to those in need.

In the Goodwill cases that KUOW reviewed, one loss prevention officer did note that he gave dry socks from a salvage bin to a man who came in with wet shoes and attempted to leave with dry ones. He was nevertheless charged for theft, pleaded guilty and sentenced to 20 days in jail.

Correction, 4/18/2019: The original version of this story misstated the amount of money Seattle Goodwill receives from philanthropy and investments.