A heroin needle broke off in her neck. It ended up saving her life.

A story about the connection between one patient and her doctor —and how more hospital emergency rooms are becoming entryways to drug treatment.

Justina Bauthues tried to get help dozens of times during the eight years she spent addicted to heroin. But the right kind of help was always out of reach.

“I used up all nine of my lives for sure,” Bauthues said.

A few years ago, Bauthues was living in her car near the US-Canada border. She stole food to eat and items to sell for drugs.

“I was in trouble with the law. As low as you could possibly get,” she said.

Injecting heroin left a mark: scars along her arms, legs and one on her neck. It’s pretty subtle, half way up on the right side, nestled in a crease.

Sponsored

“I was using in my jugular because I didn't have any other veins left,” Bauthues said.

When the tip of a needle broke off in her neck, it missed her jugular and became lodged in the surrounding tissue. It actually didn’t hurt, she said — it didn’t feel like anything.

Afraid of the nurses’ judgment, Bauthues didn’t go to nearest hospital in Bellingham.

“I didn't want to be shamed and because it was a shameful thing.”

Instead she tried to take it out on her own with tweezers.

Sponsored

“Which obviously didn't work and just made it angry and infected,” Bauthues said.

Finally, her boyfriend said enough is enough and he drove her an hour away to the ER at Skagit Valley Hospital where Dr. Shawna Laursen was on duty.

“I remember the triage nurse coming back and rolling her eyes like, ‘Oh my god. This woman's got a needle in her neck,’” Laursen said.

Laursen understands that reaction.

“You see addiction all the time and you see people with addiction at their very worst. Again and again and again,” Laursen said. “It's hard to not get a bit jaded.”

Sponsored

Long before Bauthues showed up in that ER, however, Dr. Laursen developed a mission to treat patients differently.

“I consciously sat down and I'm like, ‘I give you’ — speaking to myself — ‘permission to spend all the time you need with at least one patient a day. To be completely compassionate and actually connect with them at a personal level because it's what I need as a physician,’” Laursen remembers telling herself.

That's what Dr. Laursen did the day Bauthues came into the ER. The way Laursen spoke to her sparked a change.

“She was encouraging and she told me I'm too beautiful to die this way,” Bauthues remembered.

Laursen also gave Bauthues an option of what painkiller she wanted for after surgery, and she set up an aftercare appointment.

Sponsored

“I had never experienced that before in any other hospital.”

The doctor also prescribed Bauthues the medication Suboxone, which is used for pain and also as an addiction treatment medication to get off heroin.

Usually, patients don’t get help treating opioid addiction in the emergency room. That’s just not how most ERs are set up. But that is changing around the Pacific Northwest. From Spokane to Seattle to Portland, more and more emergency departments are becoming gateways to the medication and services that people with opioid use disorder need to reclaim their lives.

To see an example, last year I went to Swedish Hospital in Edmonds, where the beeps and pings of medical machines filled the air.

“The sounds that you hear right now, those are very comforting sounds to me,” emergency medicine physician Dr. Gregg Miller said as he gave me a tour. “That kind of repetitive ‘bing bing’ is like the little Buddhist bell ringing like, ‘I'm still alive! My heart's still beating!”

Sponsored

Something you need to know about the ER: it’s not like what you see on TV. Instead, it’s the last safety net for the sickest, most marginalized people. Your elderly neighbor who lives alone, Miller said, homeless people without shelter.

And drugs and alcohol lead to a lot of visits. That’s one reason why doctors like Miller think getting emergency departments involved with addiction treatment is promising.

But the hospitals need more than doctors to make it work.

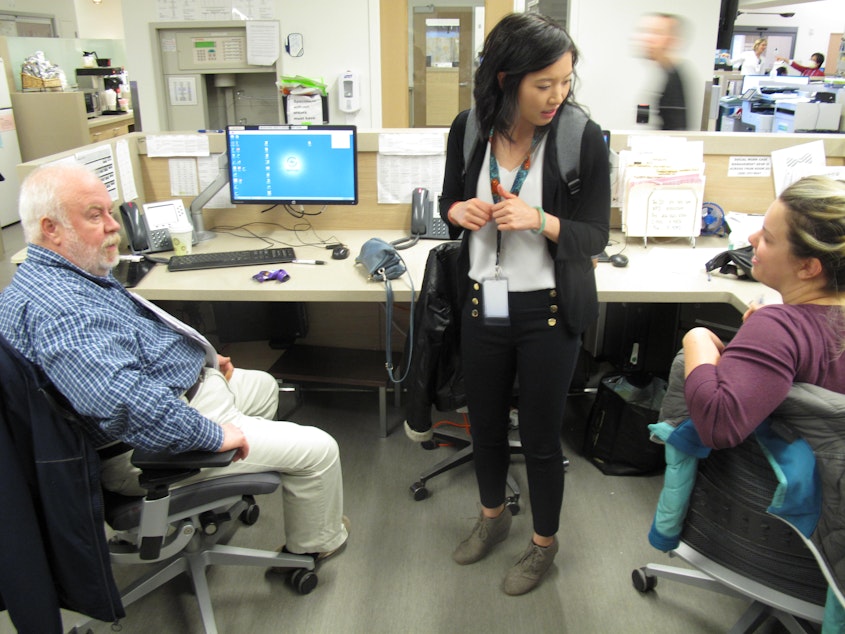

Huynh Chhor leads the counseling and social work team that sits in the middle of the Swedish Edmonds emergency department. Under the old system, social workers would print out a list of addresses and phone numbers for detox, drug treatment, or homeless shelters. Then they would encourage patients to call on their own.

“I think we saw very quickly that it was ineffective,” Chhor said. “People kept coming back in the same situation, presenting the same way.”

Now, Chorr and her staff are the ones making phone calls and introductions. They reach out to other people and organizations who can help patients get a bed at a drug treatment program, a ride, food, and even a place to stay.

If a patient wants it, doctors will prescribe opioid treatment medication in the ER, and then the social workers will make follow-up medical appointments, even the same day, at an addiction clinic.

All the patients get a phone call.

“Even patients who are unwilling to accept additional resources will tell us, 'I'm really grateful that you called.' They'll tell us that it means a lot to know that there are people thinking about them,” she said.

If the patient ever changes their mind and wants help, they can come back.

For Justina Bauthues -- who came into an ER with a needle in her neck -- she’s far beyond heroin now. She's been off drugs for more than a year and a half and getting her life back on track.

For her, it wasn’t a matter of hitting bottom. It wasn’t that a needle got stuck in her neck. It’s who she met: a doctor with a personal mission not to get jaded.

“She showed me compassion and love. She's the one that pushed me towards getting help for myself for sure,” Bauthues said.

Receiving that compassion taught her a lesson.

“That I am worth living.”

This story was originally reported by Finding Fixes, a podcast about solutions to the opioid epidemic, which is a project of InvestigateWest.