A 4-day school week? These Pacific Northwest districts are trying it out

O

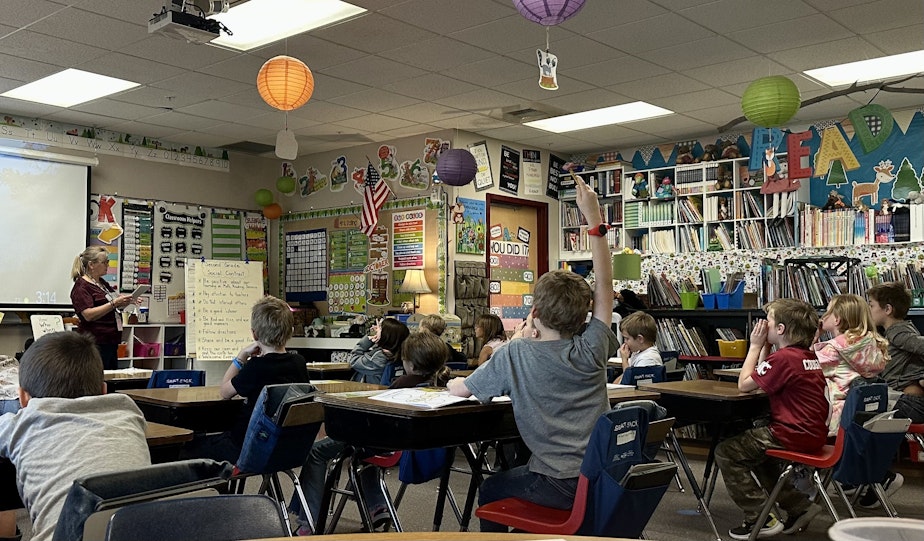

n a sunny October afternoon, Lailee Daling's second graders loaded up their backpacks and lined up at the classroom door.

The students energetically — and loudly — chattered amongst themselves as they put their coats on. Daling wished them a great weekend.

The excitement was palpable, and it felt like the typical scene of a Friday afternoon at school.

But it was actually only Thursday.

In the tiny town of Waterville, Thursdays have become the new Fridays for nearly 300 students.

The rural district in Eastern Washington is one of 10 districts in Washington state that now operate on a four-day school schedule.

Across the nation, the trend toward four-day school weeks is picking up speed. More than 1,600 schools across 24 states now have four-day weeks. In Oregon, almost a third of districts have adopted the model.

Historically, schools have predominantly shifted to a four-day week in hopes it would save money. There are some savings from this new schedule in Waterville, but that wasn’t the main reason the district made the shift in 2018.

Instead, it was to help attract and maintain good teachers.

While Waterville does its best to pay teachers competitive wages, Superintendent Penny Brown says the district — like many others in small towns and rural areas — has extremely limited finances.

If they can’t pay teachers more, Waterville leaders asked themselves: What else can we do to attract educators and keep them here?

“We’ve attracted a few that have said, ‘Yeah, I would opt to work four days,’” Brown said. “Maybe I don’t make as much as I would in a bigger district, but the camaraderie and the relationships with kids, and then this icing on the cake with a four-day week? This is where I want to be.”

And it’s worked. Waterville teachers say the shortened work week has made a big impact.

“Personally, for me, it’s huge,” said Justin Grillo, a fourth grade teacher at Waterville, “because I have a lot of other stuff that I do besides teach, and that three-day weekend allows me to have the space to do that.”

Teachers have most Fridays off, and once a month, come in for professional development.

Grillo thinks the change has made him and his colleagues better educators — and the benefits really stood out during the pandemic.

Grillo remembered the district first shut down because of Covid on a Thursday. Teachers used Friday to prepare, and they were able to jump into online learning by Monday.

“We were able to function through it way better because we had the space of Friday to help us try to rejuvenate or rethink how we were doing things every single week,” Grillo said. “That’s one of the things that I think we can be pretty proud of here at Waterville.”

Research on four-day weeks is limited and mixed

Paul Thompson, a professor at Oregon State University who studies four-day school, says Covid may be partially responsible for the growing number of schools across the U.S. shifting to the shortened week.

Thompson said the trend first started in the 1980s in western states with a large number of rural schools, such as Oregon.

The Great Recession of the 2000s prompted another wave, Thompson said, and this one may be a signal of how the pandemic changed the ways people and employers think about work.

“Now we’re starting to see even a greater wave here post-pandemic, as schools kind of wrestle with how to deal with teacher shortages, staff burnout, these types of questions, which are very difficult when you can’t necessarily pay teachers more,” Thompson said.

But there’s limited research on whether the shorter week is good for students.

Thompson has heard anecdotal stories that districts have saved big on bussing and staffing in some places, but a national study he did found the shortened week typically amounts to minimal savings of 2% or less.

His studies have also found academic achievement can suffer if a four-day week means significantly less instruction time — especially for younger students. The model works better, Thompson said, if the school day is extended or the “day off” is used for enrichment activities.

But Thompson also stressed that little is known about the effects of the schedule, and the model looks drastically different in different districts and states.

“I think we’re starting to better understand it, but give us another five to 10 years and we might know a bit more to definitively say how this will go,” Thompson said.

In Washington, state law requires the same amount of instruction times, even when a school drops down to four days.

So in Waterville, school days are now 45 minutes longer and students get a shorter lunch break to make up for the lost time on Fridays.

And as for academic achievement, Waterville students made some gains before the pandemic caused widespread learning loss across the country.

During the first couple years of the change, Waterville’s state test scores in math and English-language arts improved, as did attendance rates.

After switching to a four-day week, ‘you can’t really go back’

On the playground after school, it seems like Waterville families are now in the swing of the new normal.

Parents say the transition was tough. Child care can be tricky — especially since the town’s one day care provider recently shut down — and students lost out on free meals typically provided by the school on Fridays.

Still, parents, students, and teachers all seem to agree the new schedule works well for them.

Marshall Mires was in seventh grade when Waterville transitioned to four-day weeks. At first, Mires recalled some of his classmates dreaded the longer school day. But Mires said their attitudes changed quickly once they stopped having to wake up bright and early for school Friday mornings.

Now, Mires is a Waterville High School senior who plays football, basketball, and baseball. Mires typically has practice and games on Friday afternoons. But he said having most of the day off allows him to work a few extra hours at the town store and catch up on homework and much-needed sleep — especially if he had a late game the night before.

“It’s great,” Mires said. “After not having to go to school on Fridays, you can’t really go back to it I don’t think.”

Bryanna Sielsby, the mom of a kindergartner, says, overall, the schedule seems to be a win for families.

“I feel like they really get that mental break, and then Monday they’re rested up and ready again,” Sielsby said, as she watched her two kids run around the playground. “Weekends can feel busy. Saturday, you have sports, and Sunday, you have church and you’re grocery shopping and (the schedule) gives that extra time.”

Sielsby is a stay-at-home mom and doesn’t struggle to find child care, but she knows other families do. That’s why she takes care of one of her daughter’s classmates every Friday.

And it turns out, a piece of the town’s child care solution was hiding in plain sight.

With no school on Fridays, a growing number of high school students are using the day to work — including as the town’s newest babysitters.