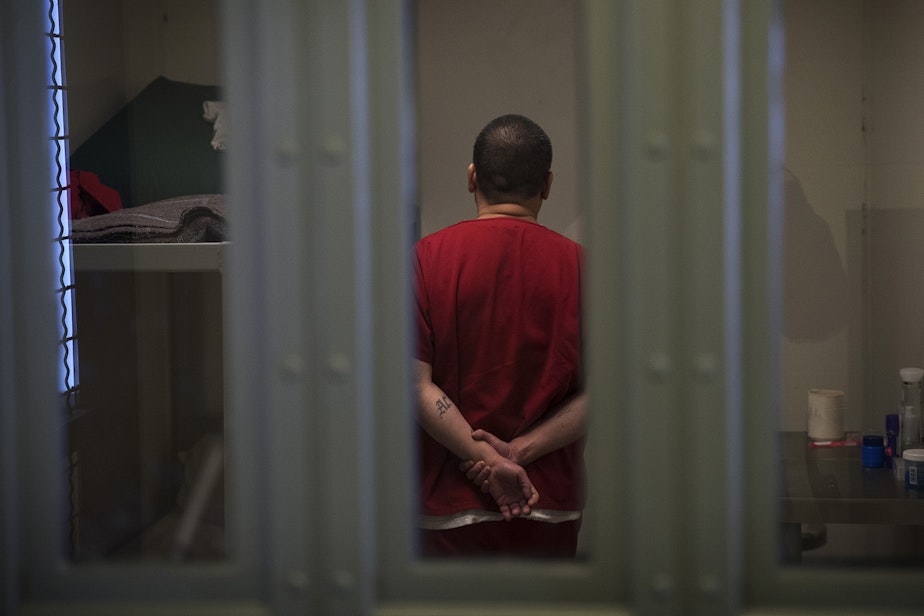

He spent 20 days in solitary in Tacoma's immigrant jail. Others spend far longer

Immigrants who land at Tacoma's detention center spend two months in isolation, on average.

The impacts can last far longer.

Raul wears a baseball hat, turned backward. Behind his ear, a number 2 pencil. He works construction, building cabinets so it’s always handy.

Raul, which isn't his real name, entered the U.S. illegally from Mexico with his wife and two kids.

He wound up in detention at the Northwest ICE Processing Center (previously known as the Northwest Detention Center) in 2013, after being stopped by police for driving under the influence.

Raul went on a hunger strike to protest jail conditions ... and then landed in solitary. It’s routine for ICE to put detainees in solitary to monitor their health but it's unclear if officials placed him there for that reason, or as a disciplinary action.

Speaking in Spanish, Raul said he has suffered psychologically since being in solitary.

Sponsored

“Not eating doesn't affect me as much as being alone," he said. "Anyone can stop eating one, two days. But not everyone can withstand being locked up alone."

Raul described the room as brick walls painted white, with no windows — the size of a parking space. An ICE manual indicates segregation rooms are 60 square feet.

He said he was there 20 to 30 days, but he's not sure. He lost track of time.

He said the hallway lights were always on ... and he could hear people talking to themselves or yelling.

Sponsored

To pass the time, he read the one thing available to him — a Bible.

When I ask if his time in detention changed him, he shrugs it off. I ask instead, what do his friends say?

His friends say he’s quieter now, he said, more reserved. And he doesn’t go out; instead he stays in his room.

R

aul is one of 272 cases of people who were in solitary confinement at Northwest ICE Processing Center between 2013 to 2017. That’s according to public data obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Sponsored

(Some of those cases may be detainees who had repeat instances in solitary confinement. The data available has removed the names of detainees so it’s not possible to verify.)

On average, segregation at the Tacoma detention center lasted 51 days.

The longest case of solitary was 781 days — more than two years.

Sponsored

Nathalie Asher, the field office director for Immigration and Customs Enforcement in the Northwest pushed back on those numbers: “We use segregation as a last resort.”

She noted that a fraction of detainees end up in solitary. And not all detainees are there for disciplinary reasons. Some are there for their own protection if they don't feel safe in a group setting.

For example, rival gang members are kept in separate quarters. Sometimes it’s for medical reasons, like if someone is quarantined for the flu or on a hunger strike.

In the rare instance there is no room in the medical unit, detainees with mental health problems may also end up in solitary.

Sponsored

“They're being very, very closely monitored by our mental health staff,” Asher said. “It may be best for the safety and, frankly, the monitoring and care of the detainees to be in administrative segregation.”

A third of the cases between 2013 to 2017 had mental health flags on their profiles.

That means that at some point either before, during, or after their stay in solitary, detainees showed symptoms of mental illness.

B

eth Farmer is a licensed clinical social worker with the International Rescue Committee, a non-profit that works with immigrants and refugees.

Part of Farmer’s work is conducting mental health evaluations for people’s immigration cases. She’s evaluated dozens of people since 2012. Some were asylum seekers detained in Tacoma.

“It's accepted that solitary confinement does make people's mental health symptoms much, much worse,” Farmer said.

According to a United Nations report, solitary should be used in rare cases. And not at all for youth and individuals with mental illness.

Farmer said even with healthy individuals, solitary can have an adverse impact.

“Isolation makes depression much worse," she said. "That sense of hopelessness, helplessness, not being able to have social interactions."

B

ack at Raul’s apartment, the room is sparse. A couch but no pictures on the white walls, no decorations.

His bedroom is a bed, with baseball hats lining a shelf.

Raul spent two and a half years fighting his deportation from inside the detention center.

He was eventually deported back to Mexico in 2016. “After everything, I got separated from my family,” he said.

He said it was hard to stay connected to his wife and children. Money was tight, and he missed birthdays and holidays. He and his wife separated.

“When you lose everything," he said, "you lose fear too."

Within months of being deported, Raul returned to the U.S., risking detention yet again.

"At least this time, I'm ready," he said. "I would know what would happen.”