Why Police Lineups Often Fail

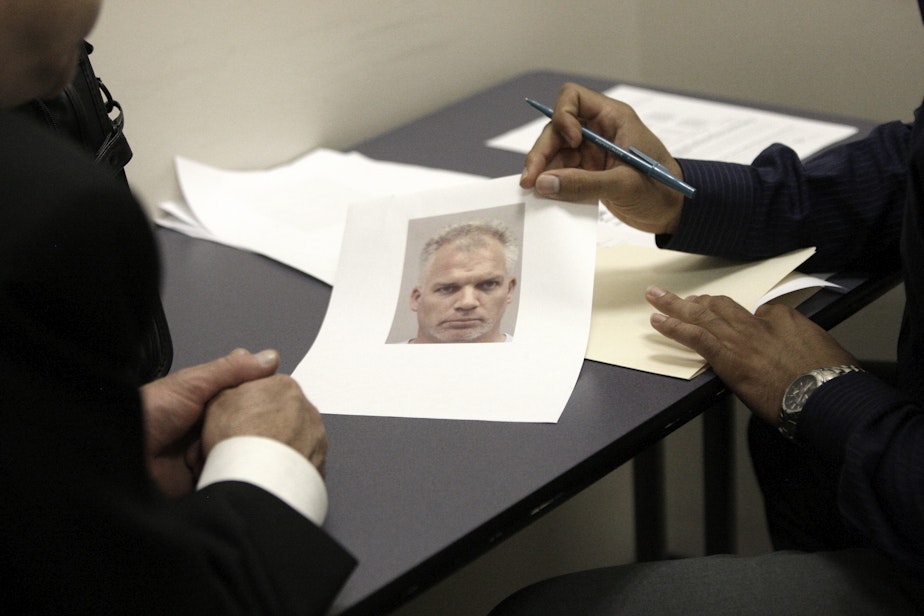

You see someone get assaulted. The cops ask you come down to the police station to check out a photo lineup.

You pick the wrong person. It wasn’t malicious on your part – it was normal. Witnesses often identify the wrong suspect, according to Lara Zarowsky, policy director for The Innocence Project Northwest.

She says mistaken eyewitness identification is the leading cause of wrongful conviction – a contributing factor in 74 percent of cases in which the accused were later found innocent.

“At the most basic level there's nothing wrong with doing a lineup,” Zarowsky says. The problem, she says, lies in how they’re conducted.

She says the person administering the lineup or handling the witness should not know who the suspect is – that could sway the witness.

Sponsored

And the lineup should be made up of people who resemble the description given by the witness – rather than a row of people who look like the person the police suspect.

Witnesses also should be told that their person may not be in the lineup, she says. Many feel the need to identify someone, fearing the investigation would end if they don’t.

Zarowsky said the lineup can also clear an innocent person, which she says is just as important as finding the actual perpetrator.

Finally, police should ask the witness to complete a confidence statement.

“There's a phenomenon particularly in terms of weak memory IDs, where a person will become more and more confident,” she says. “By the time the trial comes around, what may have been a sort of weak identification, they've now become 150 percent sure that this was the person who did it.”

Sponsored

In Washington state, co-defendants Larry Davis and Alan Northrop were wrongfully convicted of rape in La Center, Washington, in 1993. A house cleaner said that two men, one with dark hair and one with blond hair, had attacked her. Police put a description out to the public, and someone noted that Davis and Northrop were friends in the area who fit that description.

“Both served 17 1/2 years in prison before they were exonerated by DNA,” Zarowsky says. “Their case was practically a textbook example of what not to do when doing identification procedures.”

So why bother with eye witness identification at all?

“It's a difficult issue any time a tradition that has been so widely used for so long is challenged,” Zarowsky says. “I do firmly believe however that this is just a matter of getting the right information to law enforcement.”