When it comes to race and idealism 'good intentions are not enough'

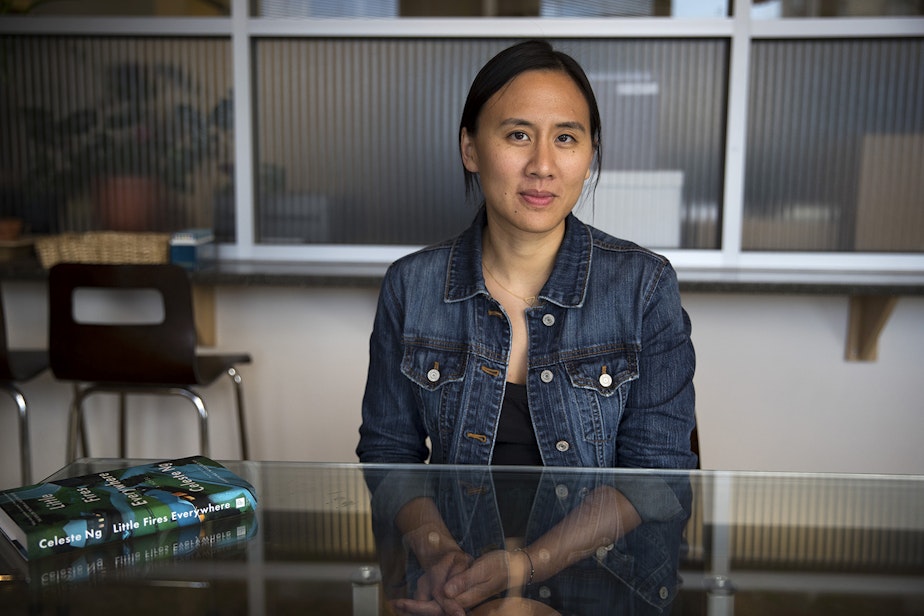

Celeste Ng’s sophomore novel, "Little Fires Everywhere," is set in her hometown of Shaker Heights, Ohio. But she sees more than a few commonalities between her town and ours.

“Seattle, like Shaker Heights, tries to live with its eyes on the world,” Ng said, speaking with Bill Radke on KUOW's The Record.

Shaker Heights is an idealistic town, whose vision extends all the way down to garbage collection. To keep the streets from looking cluttered, trash and recycling bins in Shaker Heights are placed at the back of people’s homes.

But that level of perfectionism often breaks down in the face of thorny social issues. “The problem is that ideals are very neat,” Ng said. “Real life, and humans, are very messy. And I think that’s where you run into trouble.”

Particularly for residents of progressive cities, that rubber is currently meeting the road. Ng began her book in 2009 and finished it in 2015.

Sponsored

Following the election, she said, “the words on the page are the same, but we read them in a really different light now. There’s a conflict between idealism and action; we hold tight to our principles, until they run into our discomfort.”

A recent Ijeoma Oluo piece spells out the ways in which those comfort levels are dictated by our racial identities. Ng, whose husband is Caucasian, agrees.

“Only white people get to not see race. If you talk to someone black, or Latino, or Asian, they probably see race. There’s no option for them not to," she said.

"To say to a person of color, or member of any marginalized group, ‘I don’t see the thing that makes you different,’ is to ignore something that has probably shaped their entire reality. And it’s going to be hard to reach a real understanding if you leave out that huge part of their lives.”

When white people are called out on those blind spots, often the discomfort is too much for them to bear. It get turned outward, Ng argues, toward the group or person who seems to be the cause of their unease.

Sponsored

In the case of the recent NFL protests, for example, she said the reaction has been to turn on the players as agitators who are making their mostly white fans uncomfortable. “I don’t have an issue with what you’re saying,” Ng said the argument goes, “but the way you’re protesting is wrong.”

“I have a friend who always says, ‘I can tell when I’m going to learn something because I become very uncomfortable.’” Ng argues that that discomfort is necessary to move our national conversation forward.

“I think white privilege is a little bit like if you inherit money from your parents and then you find out that that money came from a crime. It’s a little bit of that feeling: 'Well, I didn’t commit this crime. Why should I have to give up the money?”

These and other questions, she said, have always been there. But as long as she has a platform, Ng is committed to the use of fiction to bring them into the light.