Washington state and tribal sovereignty: What a recent SCOTUS ruling could mean for Indigenous peoples in the PNW

Many facets of tribal sovereignty in our country are now in limbo after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled states have the power to intervene in criminal cases involving non-Native people in Indian Country.

That means state law enforcement agencies can prosecute crimes that have historically been handled by the tribes, which experts say will further complicate an already complex area of criminal law.

But the implications go far beyond criminal justice on Native lands.

"It could interfere with in matters that are purely internal to the tribes," says Eric Eberhard, a former deputy attorney general for the Navajo Nation and an affiliate assistant professor at the University of Washington School of Law. "It could interfere in other areas of federal law where Congress has authorized the tribes to exercise civil regulatory authority over non-Native people."

That may include environmental regulations or even cases involving the Indian Child Welfare Act.

In short, Eberhard says, the ruling introduces "a level of new and unwelcome uncertainty" to how tribal laws intersects — or don't — with state and federal law.

"First and foremost, it's a profound lack of respect," he says. "And it signals that the court doesn't feel that it's bound by the most basic constitutional restraints when it comes to addressing the sovereignty of the tribes."

Eberhard spoke with KUOW's Angela King to explain what the court's ruling means and how results may vary from Washington state to Oklahoma, where the Supreme Court case originated.

Sponsored

This interview with Eric Eberhard has been edited for clarity.

Angela King: So, basically, it sounds like the issue of tribal sovereignty has been hacked here by this ruling.

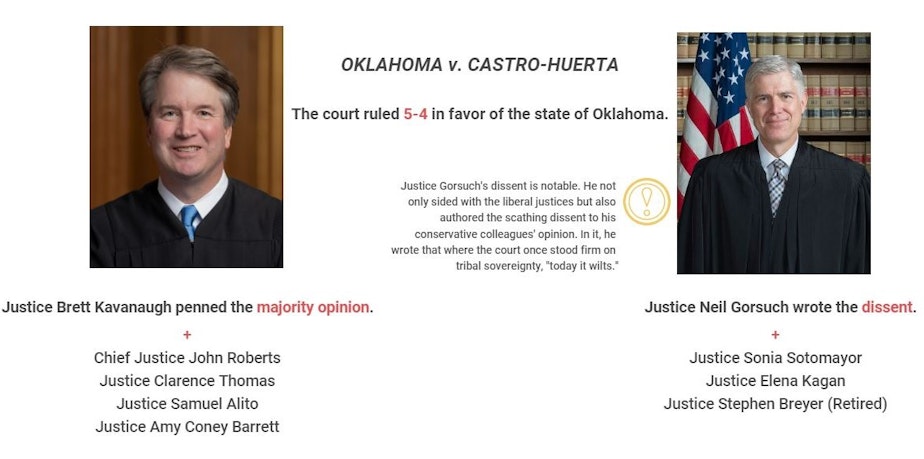

Eric Eberhard: The ruling in Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta creates new law. It effectively says that, in Indian country, states have jurisdiction to enforce state criminal law in crimes involving a non-Native defendant and a Native victim (crimes targeting Indigenous people). Historically, the states never had that jurisdiction (unless they were given permission by an act of Congress). And the Supreme Court now says they do.

It's a bit like what we're experiencing now in the court's decision to overturn Roe v. Wade. I don't mean any offense by this: When the Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization decision came down, one of my reactions was, "Well, America, welcome to Indian country. This is what the court does."

Sponsored

There is a mountain of work ahead, I guess I would say, as a result of this case. That's one way to put it. They took a very complicated situation and managed to make it much much worse.

The precedent actually goes back to the colonial era. It really was characterized by what's known as the Royal Proclamation of 1763 that was issued by King George III of England. It defined the relationship between the king as sovereign and the tribes as sovereigns, and the relationship of the colonies to the the tribes in the view of the king. That relationship really formed the basis for what was carried into Article I of the United States Constitution, which addresses the powers of the Congress. It invested in the Congress exclusive authority with respect to the tribes, with a few exceptions in the president's treaty-making power. Those are the basic touchstones that have been carried forward into the so-called modern era.

The court acted in a way that really has no basis either in history, fact or the U.S. Constitution. That is, at the minimum, surprising for a group of justices who take great pride in being originalists and in interpreting the Constitution as it was understood at the time that it was adopted.

That being said, were you surprised that Justice Neil Gorsuch dissented?

Sponsored

No. It's entirely consistent with his understanding — in fact, with what I view as the appropriate understanding — of the relationship of the tribes as sovereigns, the United States as sovereign and the states as sovereigns. The tribes are not subsidiary entities to the states under the U.S. Constitution. They are sovereigns dealt with directly by the United States under the U.S. Constitution.

And of course, there's the cultural aspect of this as well.

Yes, it's profound. Sovereignty in Indian country is cultural. Everything in Indian country is cultural. That's a difficult concept for non-Native people to grasp. There's just a huge chasm between most Natives and most non-Natives on those core understandings. I think it's fair to say that almost every Native person would look at this decision as an offense to the basic sovereignty of the tribes and the cultures and customs of the tribes and a serious threat to them.

On its face, the Oklahoma case the Supreme Court used to make its ruling dealt specifically with criminal cases involving a Native victim and a non-Native perpetrator. States have not broadly had the authority to prosecute these crimes, except in very limited instances by an act of Congress. So, it sounds like the states could be wading into new areas of law. That being said, how could this ruling be interpreted differently state by state? Let's take Washington state versus Oklahoma, for example.

Well, my hope here in Washington would be that there's been enough history between the state and the tribes and the counties that the approach will be much more open, much more willing to talk about what would be effective from a law enforcement point of view. And clearly, there will be tribes that can handle this entirely on their own with the help of the U.S. attorneys, as they have for going clear back to the territorial period.

Sponsored

But as we see in Oklahoma, the state there is going to be aggressive about asserting jurisdiction, whether the tribes like it or not. They wouldn't have gone to all of this cost and expense in the litigation at the Supreme Court if they thought it could be done through discussion and cooperation. Unfortunately, I do think the tribes there were more than willing to talk to the state. I just don't think the state was willing to talk.

We've been talking a lot about the criminal aspect or the criminal cases that could fall under this ruling, but it doesn't stop there. What are other areas of law this ruling could affect?

This is a whole area of the law that has been very complex but has largely been settled for 250 years or so. And it is now unsettled. It's uncertain. What the court does in criminal law, typically, is different than what it would do in civil law. But because of the language that Justice Kavanaugh used in writing the majority opinion, there are implications in the case that the court will apply this same view and the same policy in civil matters involving the tribes. And that could become very disruptive.

People of good will, in state governments, will try to work with the tribes to actually enhance tribal authority, rather than undermine it. And I think within states, there'll be variations from county to county because of the structure of the criminal justice system in the states. County attorneys, county prosecutors, county sheriffs exercise a certain degree of authority that is discretionary. How they choose to use that will have immediate impacts in Indian country.

It's like a picnic feast for non-Natives who want to engage in elder abuse, child abuse, women abuse, you name it. And it will be difficult for the tribes to do anything about it.

Sponsored

You clearly disagree with his ruling, and as you've laid out, there are several legal questions that are now popping up. What can be done, though, outside of the courts?

I'd like to see Congress enact legislation that effectively nullifies the decision of the court and the Congress has the power to do that. It'll be very difficult in the near term. When the Supreme Court decided the Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe case here in Washington in 1978, it also was a radical departure from the core doctrines and understandings of what we call federal Indian law. And it's taken 30 years for Congress to begin to fashion real remedies for that decision. So, it will take some time, but I think ultimately, Congress will intervene and impose a structure for criminal justice in Indian country that respects tribal sovereignty.

Remind us what the Oliphant case was about and the effect it had.

The Oliphant case arose on the Suquamish reservation and involved the arrest of a non-Native by the tribe's police for DUI on the reservation. It ended up at the U.S. Supreme Court, which used the case to proclaim that tribes have no criminal jurisdiction over non-Native people engaged in the commission of crimes on the reservations. And that created a huge law enforcement void in Indian country, which is a key element today in the abuse of Native women, elders and children by non-Native people. It was unhinged from the law, just like this decision is unhinged from history and the law.

The U.S. attorneys, theoretically, have jurisdiction over a lot of these violence issues under the Major Crimes Act, as it's known, and the Indian Country Crimes Act. But the U.S. attorneys don't have the resources to enforce federal law against the non-Native offenders, creating a vacuum of law enforcement. That has started to be filled by amendments to the Violence Against Women Act to finally recognize and affirm that the tribes do have criminal jurisdiction over non-Natives. But it's very limited, and it is taking the tribes time to gear up to be able to exercise that authority.

We're going see that same kind of void now in various parts of Indian country as a result of the Castro-Huerta decision. There is no doubt that it created a climate that invited those kinds of characters onto the reservations to try to take advantage.