This former cult member is helping 'deprogram' QAnon believers

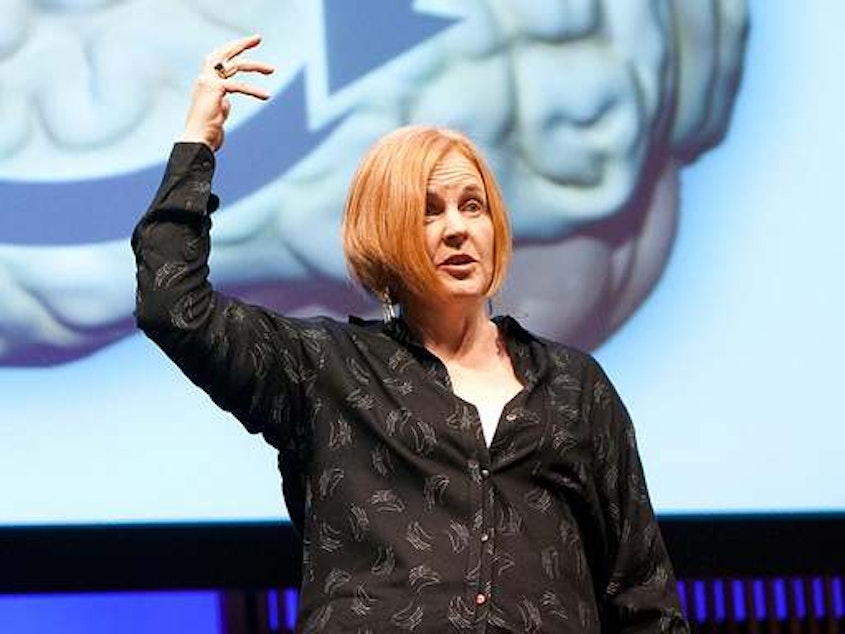

When Diane Benscoter was 17, she met "the Messiah."

His name was Sun Myung Moon, the leader of a religious cult called the Unification Church. Benscoter joined "the Moonies," as Moon's followers came to be known, and spent the next five years of her life believing she'd found her purpose — even if she had to give her life for it.

"It was the most invigorating feeling that I had ever experienced ... I suddenly knew what my life was about," Benscoter said. "And honestly, I don't know if I'll ever feel that much security, that much excitement again in my whole life."

That feeling may be impossible to replicate, but her time with the Unification Church did give Benscoter something to fight for: People who are being manipulated today like she once was.

For the "Moonies," it was all about Sun Myung Moon; for thousands of people today, it's "QAnon."

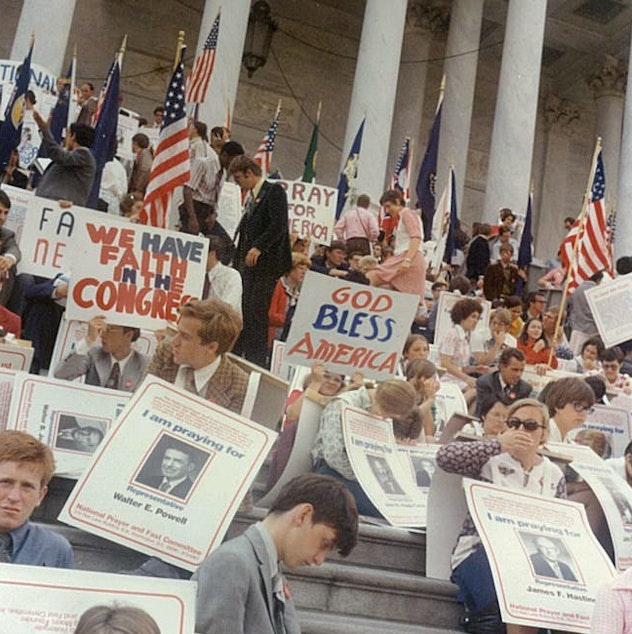

QAnon was borne out of the far-right political movement, when an anonymous person, or persons, identified only as "Q" began posting elaborate conspiracy theories. Q claims to have inside knowledge of government secrets and has spread a range of lies, not unlike Moon; just as Moon claimed to be "the Messiah," Q has painted former President Donald Trump as a savior figure.

Benscoter's organization, Antidote, will soon offer workshops — consisting of eight, 90-minute sessions — to help participants learn how to break people away from QAnon. Antidote is scaling the individualized deprogramming techniques that saved Benscoter and others from cults in the past.

Sponsored

Like Moon, the disinformation spread by Q plays off people's fears and takes advantage of human vulnerability, Benscoter said.

And as the movement has grown, U.S. authorities increasingly see QAnon as a domestic terror threat, one that reaches across the globe, thanks to the internet.

Antidote's workshops will launch this spring; in the meantime, anyone in need of help can reach out to Antidote online.

Is QAnon a cult?

QAnon has been referred to as a cult, a political movement, and a worldview, among other things. Giving it a concrete definition is as difficult as mapping the range of ideas contained within it.

Sponsored

Catherine Wessinger is a professor of the history of religions at Loyola University New Orleans. In an article for the independent Religion Dispatches, Wessinger argues that describing QAnon as a cult is inaccurate and ineffective at helping people see the truth.

Benscoter agrees that QAnon is not what we think of as a "traditional cult."

But she argues that at QAnon's core, it functions the same way as a cult.

Sponsored

"On a psychological level, what's happening with so many people today is that they're experiencing the same all-or-nothing commitment, and the enemy is anyone who believes different than them," she said.

QAnon followers, like the Moonies, are being psychologically manipulated, Benscoter said. Their preconceived notions about shadowy forces, like "Big Government" and "Big Pharma," are validated. And they believe that they're the ones who know "the truth."

Benscoter explained the mindset that led her, and now QAnon followers, to believe they have been "chosen."

"They're the ones that understand what's important in life. They're the ones that are fighting the good fight."

Sponsored

What's the point of spreading disinformation?

Cults like the Unification Church become defined by their leaders. They maintain their power by defining a "right" and "wrong" side of society.

Benscoter said QAnon beliefs function similarly; they thrive and become dangerous through extreme polarization.

"If you're an authoritarian leader, and you want to take over the country, for instance, you can work in a bunch of different areas to create an us-versus-them mentality for a large population," she said. "People will be willing to fight and give their lives, take up weapons if necessary, for the side that you've created."

Consider the U.S. Capitol insurrection on Jan. 6, 2021.

Sponsored

That attack, which featured people and messages associated with QAnon, was predicated, in part, on what is known as "the Big Lie." Believers in the conspiracy claimed that President Joe Biden stole the 2020 election from former President Trump; there is no evidence supporting this allegation, and in fact, it has been widely disproven, including by Republican election officials.

Who is vulnerable to these ideas?

Last year, NPR's Audie Cornish told the story of a Reddit group called Q Casualties, where the family members of Q followers shared their experiences as loved ones faded out of their lives. They described a process by which their loved ones were led, click by click, down a rabbit hole of conspiracy theories.

Benscoter said she sees this play out in her inbox, which she described as an ideological "war zone."

"Some people have elderly parents and they're worried they will pass away before they're able to fix the relationship," she said. "It's just heart-wrenching."

The world of QAnon has been embraced by people who have some level of discontentment or distrust. Benscoter said she notices three dominating themes:

- An anti-Big Pharma or anti-vaccine perspective

- An anti-Big Government perspective

- Racism or white supremacist opinions

"All of these groups are doing this because they need something in life," Benscoter said. "They've been looking for something, hoping for something more meaningful in their life, and it's fed to them on a silver platter...it makes so much sense to them."

The good news is there's hope for people who are being manipulated, Benscoter said.

Rather than berating a loved one who references QAnon, she said people have to focus on rebuilding their relationships and bridging the ideological divide respectfully.

"It's so important not to make that divide wider by telling people they're crazy or by shoving a pile of information at them," she said. "Remember, this has become their identity...when you're questioning their belief system, when you're questioning where they get their facts, you're really questioning who they are as a person, and they will deflect that."

They're clinging to something like QAnon because it gives them comfort. To get away from it, they'll need a meaningful relationship to take its place, Benscoter said.

As hard as it may be, Benscoter said it's important to "remind them that you respect the fact that they're so committed to something they believe in, that they believe will make the world better."

Benscoter was deprogrammed by another ex-Moonie who helped her see she'd been taken advantage of.

"It was such a devastating moment to realize that that much of my life had been taken away from me, and that this whole thing that I committed my life to, and was willing to die for, it was all a lie," she said.

But she said she escaped the cult because someone who loved her, her mother, was willing to help her through it. Her personal experience has led her to help heal others.

"Help them remember that you love them and you miss them and you want a meaningful relationship with them," she said. "[Your] relationship is going to be the biggest asset in trying to build that bridge."