So you caught a cougar, now what?

When we started producing THE WILD podcast, I never thought I’d end up in prison. But that’s what happened anyway. All because of cougars.

I suppose I should start by explaining that researchers in the Olympic Peninsula have a lot of tech at their hands, all aimed at tracking cougars in the region. They have satellite radio collars on some cougars, as well as a grid system of nearly 100 remote camera traps. Those cameras are constantly collecting images and videos of wildlife in the forest. It creates thousands and thousands of files.

On one hand, all this tech helps signal when a cougar is in an area. Given the proper opportunity, researchers will race out to catch a cougar in the wild. Well, briefly catch a cougar.

For example, on one trip to the Olympic Peninsula, THE WILD team followed wildlife biologist Kim Sager-Fradkin with the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and Mark Elbroch with Panthera as they tracked a cougar up a tree. With the help of some dogs, and a tranquilizer gun, the research team was able to get the 175 pound cougar on the ground — it’s the largest they’ve ever studied up close.

Sponsored

They were then able to obtain fecal, hair, and other samples from the animal in its natural environment. Then they placed a collar on it, to help track it in the future. Once they were done, they gave the mountain lion a shot of something to wake it up. It came to, shook its head, looked at all of us, and walked away; leaving the team with a wealth of data to study.

It seems like a simple job — but it’s harder than it sounds.

Now, on the other hand, there is another difficult job that researchers on the Olympic Peninsula have — dealing with all the data from all the cameras. As we explained last week on The Wild, there is so much of it — photos and videos that have to be looked through, one-by-one. Every time a sensor picks up movement, the camera takes a shot. Sometimes that’s a leaf. Other times, it could be another animal. And sometimes, it’s a cougar.

Sponsored

All that media has to be observed and catalogued. It’s a monumental task. So to get it done, the researchers have gone to prison.

Cougar tracking behind bars

Early one morning, The Wild team checked into Clallam Bay Corrections Center. A guard asks us if we have any weapons, bombs, drugs, or knives. We didn’t.

Shortly after that we were led to a room with Greg Steen. He is one of about 900 incarcerated individuals at the corrections center, located way up on the Olympic Peninsula, near the most northwestern part of Washington state. There’s very little up there aside from wilderness and time.

Sponsored

Greg is 55 years old and has become a key part of the cougar study on the peninsula.

Wildlife biologist Kim Sager-Fradkin set up the cameras in the peninsula with Dr. Mark Elbroch. He’s with Panthera, a conservation group dedicated to wild cats like cougars. Someone has to click through every video and photo taken by the cameras, some of which are not far from the prison itself.

That someone is Greg, and a handful of other incarcerated individuals. They catalog the videos. Greg volunteers for the wildlife project as part of an environmental science class he’s taking at the prison.

Sponsored

“It allows us to kind of extend from our classroom environment and actually, I think she called it ‘citizen biologist or zoologist,” Greg says.

They watch every video to see what has been recorded, which species, and even what the animals are doing. Then the key part is taking that information and getting it into a database. Kim and her small team just don’t have the time.

“We have a little time on our hands in here to review things,” Greg said. “And yeah, she just came in here and told us what to do and left us, you know, and trusted that we would, you know, do as much as we can.”

Sponsored

And it’s these video clips that can reveal gems of secret cougar behavior.

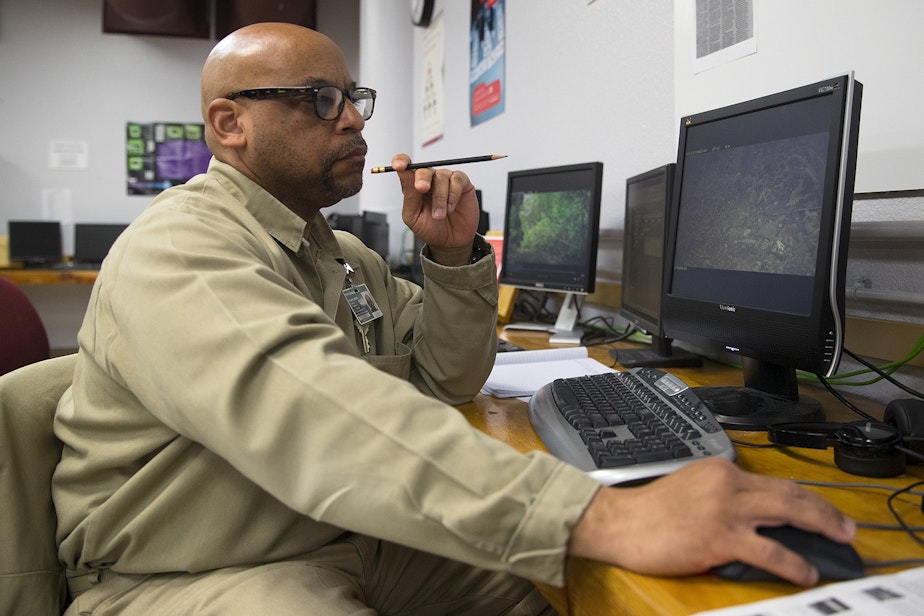

Greg is sitting at one of five computer screens in the prison classroom. His eyes scan the footage. He clicks away with his mouse and notes the date and time each video was taken. Greg then watches and classifies every video, examining them carefully for every detail.

Sometimes it’s a leaf that triggered the camera's motion sensor. There’s nothing significant on many of the videos. Every so often, though, there is an animal. If they’re lucky, it’s a cougar. Greg shows me one recent video with a cougar actually sharing a kill — with a skunk!

“...the spotted skunk is interacting with the cougar around this kill site, you know, who would have thought that something like that would happen?” Greg says.

Surprisingly, cougars don’t seem to mind all that much if a smaller animal wants to share a meal. Or maybe it knows better than to mess with the tail end of a skunk.

Once Greg has a video with some action, he then clicks on a list of options to describe the behavior of the animal.

“So you’ve got all kinds of options here,” Greg said while going through a list of behaviors. “You got, ‘feeding,’ ‘playing,’ ‘interacting,’ ‘resting,’ ‘catching,’ approaching the camera behavior, ‘cleaning,’ ‘nothing,’ ‘walking,’ ‘moving.’”

Greg loves this part of the class. He grew up in Seattle, but he says this role has expanded the way he looks at the world around him. Even inside these walls, there’s wildlife to see and Greg has started to notice it.

For example, the the birds that fly into the prison courtyard. Birds like gulls and ravens.

“When we go eat chow, they know we come back,” Greg said of the birds. “People bring back bread and things like that. But if a seagull comes in and eats too much, the raven will come in and chase the seagull away, as if to say, you know, ‘That's enough for you.’”

“I have a pretty good shot of the exterior there,” he said, noting that he tends to watch the birds a lot. “And, you know, oftentimes you'll see this communication with the crows and the ravens and the seagulls.”

Even in this prison, the cougars are sometimes closer than you might think. One cougar had a kill site — aka a meal — just 200 yards from the facility.

“You know, we don't really, really think about the bigger ecosystem that we're in, in prison, because we're so confined,” Greg said. “But we're actually neighbors of, you know, what we're actually viewing. So it's actually good to see what's going on outside of the perimeters of the confines of any institution. It really allows your mind to kind of expand and be freer in some regards. You know, so it's rather fascinating.”

Back to the videos. Many of them aren’t super interesting, but sometimes, an eye-catching one shows up — and there’s a category for that. One option says “Hollywood?”

“Some vids, like a skunk and a cougar, you know, those are things that you wouldn't normally assume would be happening out there,” Greg explains.

Greg recalls one video with some eagles engaged in some "infighting."

"And so, you know, funny moments," he said. "Like if you were to add some type of a music bed or some type of audio, people would enjoy that viral moment.”

Greg shows me some favorite videos — more of the cougar and skunk, cougar kittens playing, adult cougars sharing meals. It’s a treasure trove. And all the while, Kim is getting the data she needs to understand these cats, and the incarcerated individuals get something out of it too.

“A lot of us don't have anything happening outside of this prison,” said Tom, who's also helping catalog the videos. “So to be a part of something that's outside of this prison kind of gives us, it lights a fire under us, you know, gives us something to feel like we're a part of that's not prison. So that's one of the things that guys take from this, aside from the fact that they just love nature.”

As we leave the prison, I glance up and catch myself looking into a security camera. They’re everywhere, quietly revealing things about those who walk by.

We walk through a series of doors while exiting the prison. Finally, through the last door and out into the fresh air. Right then, I hear something above me and I look up. And there is Greg’s raven.

THE WILD is a production of KUOW in Seattle in partnership with Chris Morgan and The UPROAR Fund. It is produced by Matt Martin and edited by Jim Gates. It is hosted, produced and written by Chris Morgan. Fact checking by Apryle Craig. Our theme music is by Michael Parker.

Follow us on Instagram (@thewildpod) for more adventures and behind the scenes action!

Editor's note 7/27/20: In the original version of this story, we mentioned the crime that lead to the conviction of one of the men we included in this story. Upon reflection, we removed that detail from the story because this is not a story about his conviction or his crime, it is a story about an education program.