A river runs through it ... once again

It started as a glacier. Then, about 13,000 years ago, it was a trickle, then a stream, and eventually a rushing river meandering through the Olympic Peninsula.

For thousands of years, life thrived off the ecosystem served by the Elwha River that fed into to the Strait of Juan De Fuca.

Then it stopped.

About 100 years ago, Canadian entrepreneur Thomas Aldwell came to the Olympic Peninsula and saw the Elwha River and was impressed by its power, rushing down from 5,000 feet in the mountains. So impressed, that he wanted to harness it. He did.

For generations, communities around Port Angeles benefited from the hydroelectric dam that Aldwell built on the river. The previous beneficiaries, however, lost access to their home.

Salmon, in particular, were cut off from spawning grounds for decades. The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe had relied on the salmon which spawned here for centuries. Birds, insects, and mammals all previously flourished because of the river. They too were impacted.

That all changed by 2014, however. Now nature is fighting its way back around the remnants of the old dam.

"You can still see a little bit of parts of the dam ... you know it just wasn't economically reasonable to remove," said Sarah Creachbaum, superintendent of the Olympic National Park while pointing to the now defunct Elwha river dam.

Dam it all to hell

Two dams were built on the river here, just outside of Port Angeles. But demand for energy outgrew their ability to provide it. In 1979, the federal government recognized that Pacific Northwest tribes had been denied historic fishing practices through dams like these.

Aldwell did not comply with a Washington state law that required the construction of fish passage around dams. He eventually agreed to build a fish hatchery in order to appease the state, but it failed and was shut down.

As the dams aged, it was decided in 1992 — through Congress' Elwha River Ecosystem and Fisheries Restoration Act — to take them down. It would take until August 24, 2014, for demolition to be completed and the Elwha River to be freed.

Suddenly, more than 70 river miles of pristine spawning habitat were available to fish. The removal was the largest line item construction project in the history of the National Park Service at $325 million.

But looking at this site now, you wouldn’t know that a giant concrete slab used to stand there. Around it, an ecosystem is changing before our eyes.

"That's sort of the fun part," Creachbaum said. "It's like this big mystery, right? What's going to happen when the fish actually get up into the upper reaches, into some of the creeks and they start to die? And different plants start to grow along the streams that give cover for different species that maybe haven't been there in our memories. What's going to happen when we have more black bears, say, coming down into the Elwha Valley? Could be really cool to see what happens."

Shocking

Not far from here, George Pess doesn't have to imagine. He's a fisheries biologist with NOAA and he's tracking juvenile fish that have been using the river since the dam was removed. While the dam came down relatively quick, biological and ecological changes — like with these fish — often take longer. If the fish are doing OK, there’s hope for the whole ecosystem.

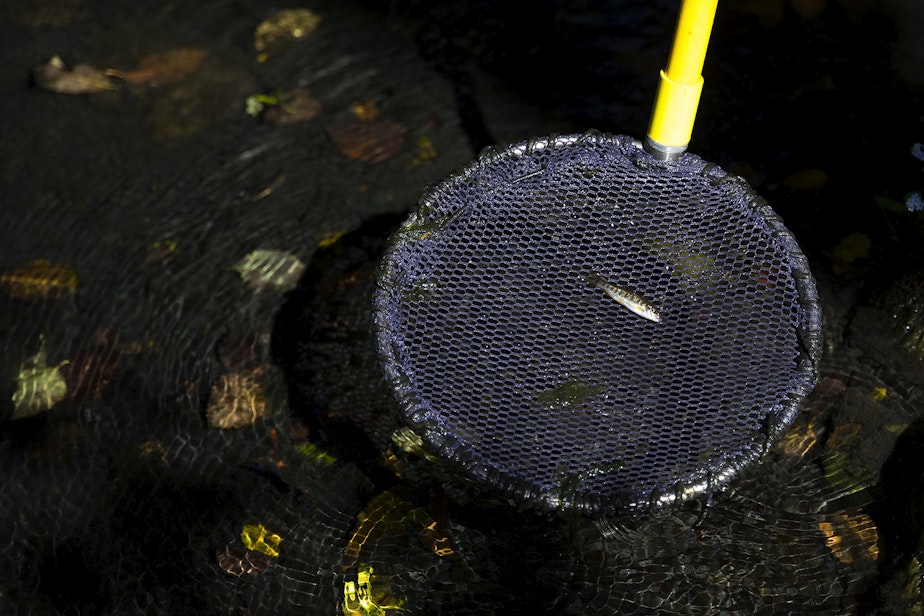

To determine this, Pess and his crew count and measure all the fish passing through an Elwha River tributary. And to do that, they have to give the fish a little electric shock.

"Basically, what is going to happen is he’s going to shock up ... he’ll stun them and you’ll just see them floating or kind of moving away and you just kind of grab them with the net and put them in the bucket," Pess said.

Just to be clear, this does not harm the fish. It briefly stuns them so Pess and his team can quickly and safely count the fish and return them to the river. After about 20 minutes of work, and some minor electric shocks, he has more than 200 fish in his bucket. They count and measure them.

From the fishes' perspective, this is akin to an alien abduction.

"Where another being is coming into your environment, stunning you, drugging you, taking something from you, putting something in you, and then releasing you back in your environment," Pess said. "You have to tell everybody that just happened and nobody believes you."

"That’s what you told you wife because you were at the bar — we know," one of the other crew members jokes.

"OK, back to business. Coho, 64," he calls out referencing the fish and its number.

Most of them are fairly small, only an inch or two. Pess also takes a DNA sample from the tail. That information will be used to see how far up the stream these fish will eventually get.

When the day is done, they count almost 400 fish.

Work like this is showing that the fish are coming back. When the dams were in place, between 500-2,000 Chinook salmon were returning each year. That number is now about 7,500. Initially, many of the returning fish were from hatcheries, managed by the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe. Now, they are counting more and more wild fish.

Above and below the water

More wild fish is an indicator — the ecosystem is changing. More life is flourishing.

Why? How?

Consider those little salmon that Pess was counting. Before, with the dam, they only had access to the lower, warmer reaches of the river. They didn't spend too much time in the river before going out to sea.

Now they spend more time here, traveling to the upper reaches where they were previously cut off. This allows them to grow slower and bigger.

Above the water, American Dipper birds are finding more food. They love insects, but now they are finding more salmon carcasses and salmon eggs to chow on. With the larger menu, many birds have opted not to migrate away and stick around through the year.

"And those are kind of like little pieces of steak or protein pills for these animals," Pess said. "So instead of having one clutch, or one set of eggs each year, they started to have two sets and they became resident dippers instead of migratory dippers."

And that's just two species — salmon and American dippers — that have been impacted by freeing the river.

"I think that the increase in the amount of different life histories that we're seeing, the increase in the numbers of fish, the increase in the distribution of where we're seeing them, all point to one thing and that means fish are utilizing areas and they're healthier and that means that the ecosystem is actually responding," Pess said.

Surf's up

While the salmon are doing their thing upstream, there are also changes at the mouth of the Elwha River, where it meets salt water.

About four years ago, the shoreline here was rocky.

"Sand and gravel was almost non existent," said Robert Elofson, an elder with the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe.

When the dam was removed, 33 million tons of sediment -- 100 years worth that had been building up behind the dam -- rushed down to the shoreline. Now, it's a sandy beach.

The sand is credited for the return of a few species. It didn't take long before tribal members started noticing Dungeness crabs in the area.

"By the next year they were out there in such numbers that some of our tribal members and some of the state harvesters started harvesting and making money," Elofson said. "Out here off the beach, in front of all this sand and gravel, because that's what they need to dig into to protect themselves. They need it for protection against the hard currents out here and from predators."

Elofson said that with the increasing salmon numbers upstream, he hopes that he can begin fishing in a couple years, like his ancestors once did, even commercially.

Looking off the shore, you can see that the sand has attracted yet another group to come populate this area.

"We got a prolific number of surfers out here and now," Elofson said. "They're coming back."

Who would have thought? Pull the dams down, bring the surfers back.

Special thanks to Washington's National Park Fund for their help with this episode.

THE WILD is a production of KUOW in Seattle in partnership with Chris Morgan Wildlife and The UPROAR Fund. It is produced by Matt Martin and edited by Jim Gates. It is hosted, produced and written by Chris Morgan. Fact checking by Apryle Craig. Our theme music is by Michael Parker.

Dyer Oxley contributed to this article.

Follow us on Instagram (@thewildpod) for more adventures and behind the scenes action!