The future of renewable energy may lie in organic waste

There are lots of renewable energy forms out there: solar, wind, hydro, and nuclear, for instance.

But Snohomish County is investing in something different — a kind of renewable energy you may not have heard of before.

It starts out in the fields of a local dairy farm.

At the Werkhoven Dairy in Monroe, Wash., there sits a big, concrete box. That box is an anaerobic digester. And Daryl Williams knows all about it.

He’s an environmental consultant for the Tulalip Tribes, as well as a tribal member. He’s also the board president of Qualco Energy, which is a partnership between the tribes and Werkhoven Dairy to run the digester.

"We actually started planning for it back in 2001, I believe," Williams said. "It was something that the tribe thought would be useful to help reduce water pollution issues from farm runoff, and thought it can also help with the economics of farm operations. And energy production was just a byproduct for us."

The digester’s been up and running since 2008.

Basically, it takes manure and food waste and heats it up. That heat speeds up the decomposition process, breaking down the waste quicker than it would naturally.

Sponsored

And when it breaks down you get two things: a nutrient rich liquid and methane gas. The nutrient rich liquid goes back to the dairy farm, to be used in place of fertilizer.

For Williams and for Werkhoven Dairy, this project is about fertilizer.

"When a farmer spreads raw manure on their fields, that takes a year to a year and a half for the nutrients in the manure to convert to a form that the crops can use," Williams said. "And during that year, year and a half, with a lot of our farmland, we get multiple floods that can wash a lot of that manure into the rivers."

The nutrient rich liquid this digester produces can be used immediately, without the year wait time. That can stop pollution from entering nearby rivers and the Puget Sound, and saves the dairy money on buying fertilizer.

That’s become even more important this year, because a lot of the United States’ fertilizer comes from Ukraine. With the war cutting off access, fertilizer prices are at near record levels.

Sponsored

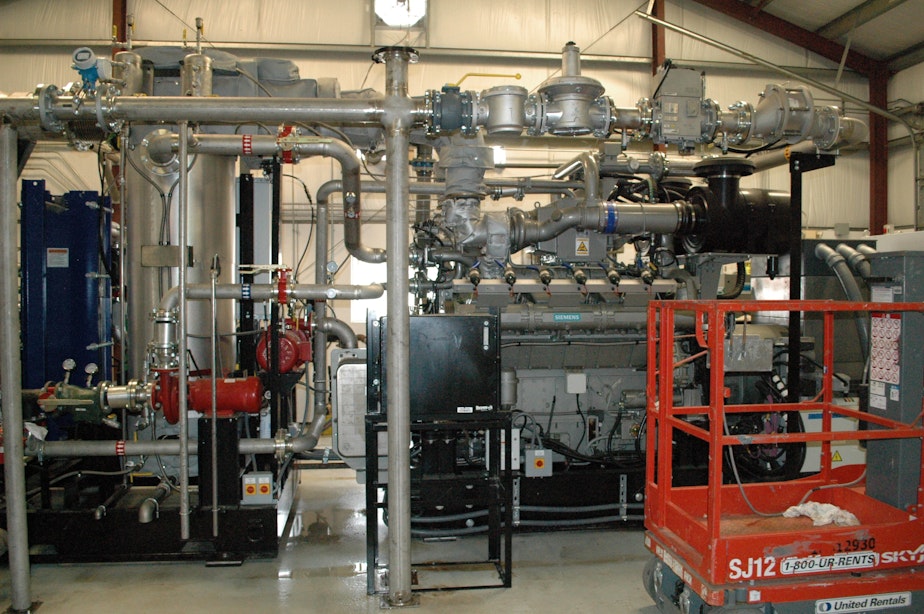

But the methane gas the digester creates also serves a purpose. It powers a generator, which creates energy. In other words, it’s renewable, transforming waste that would otherwise go to the dump or onto a field, and making something we need a whole lot of.

In 2014, Snohomish Public Utilities, or PUD, started buying that energy. Now they're going a step further.

Next week, the PUD will begin running a new generator at the site — one that produces enough power for around 675 homes.

The sale of that electricity to the county is what pays for the cost of the digester. And once the Tulalip Tribes pay the final bill for the government bond that allowed them to build the digester, which is expected to happen in December, it’ll be a fully closed system.

When this project first started, it was meant to be a demonstration — a way to get other farms and dairies across the state interested in building and maintaining their own anaerobic digester. But so far, that hasn’t really happened. Manure-to-electricity operations haven’t caught on the way some advocates were hoping they would.

Sponsored

Daryl said that right now, there are about eight digsters the size of Qualco’s in the state.

The reluctance likely comes down to cost. The food waste that partially powers the biofuel generator is harder to get in some parts of the state. And if utilities aren’t willing to pay dairies enough for the electricity produced by the anaerobic digester to cover the cost of maintaining it, for many dairy farmers, the math doesn’t work out — investing in a biofuel generator isn’t economically feasible.

That's where the state comes in. Washington's Department of Commerce has incentives that could help draw interest in creating more anaerobic digesters. Over $76 million was allocated to the Clean Energy Fund through 2023.

But to be successful, eventually, anaerobic digesters need to pay for themselves.

The Qualco anaerobic digester does pay for itself, but barely. And even just in the town of Monroe, the digester doesn’t produce enough energy to power every home.

Sponsored

But even with those issues, anaerobic digesters are worth the price, said Jim Jensen, a senior bioenergy and alternative fuel specialist at the Washington State University Energy Program.

"In the case of a bio-gas project like this, they often happen out in areas that are at the edge of the grid, so to speak. So projects like this, whether it's a digester on a farm or a solar project or wind project, somewhere out there really helps to make our grid more resilient."

Washington State University's energy program provides information and services to both state and private organizations.

Jensen said that the newly passed Inflation Reduction Act will help fund more digesters, and other bio-gas projects, on a national level. Similar funding has also passed at a state level here in Washington.

"There's going to be a lot more attention paid to this in the coming years. So the kind of project drought we've faced where there hasn't been enough support in the past decade, I think, in this decade coming forward, we're gonna see a lot of activity," Jensen said.