Seattle police stopped investigating adult sexual assaults this year, memo shows

This story was co-published by KUOW and The Seattle Times.

S

eattle police’s sexual assault and child abuse unit staff has been so depleted that it stopped assigning to detectives this year new cases with adult victims, according to an internal memo sent to interim police Chief Adrian Diaz in April.

The unit’s sergeant put her staffing crisis in stark terms.

“The community expects our agency to respond to reports of sexual violence,” Sgt. Pamela St. John wrote, “and at current staffing levels that objective is unattainable.”

Sponsored

Law enforcement agencies here and across the country have grappled with labor shortages during the pandemic and since the 2020 protests following the murder of George Floyd. But Seattle’s failure to staff its sexual assault unit stands out from other local police departments and raises questions about the Seattle Police Department’s priorities, advocates say.

The memo, sent April 11, emerged amid a wave of new political promises for policing in Seattle. Last fall, Seattle voters elected a new mayor who rejected calls to defund the police and campaigned on a platform to clear public spaces of homeless encampments and strengthen public safety.

Behind the scenes, police leaders confronting an ongoing staffing crisis shored up patrol and positions that respond to homeless encampments, while some investigative units shrunk.

Now the department’s lack of attention to its sexual assault unit is threatening the viability of cases, as delayed investigations and evidence collection possibly hinder their outcomes.

In the memo, St. John went on to say that she was not “able to assign adult sexual assault cases” that came into her unit. Cases involving children and adult cases that had a suspect in custody — a fraction of adult sexual assaults reported to police — were being prioritized. The unit just had too few detectives.

Sponsored

Those concerns bear out in fewer referrals from the sexual assault unit to prosecutors. King County prosecutors say they’ve communicated with the sexual assault unit about understaffing concerns, but little has changed.

Assistant Chief Deanna Nollette in an interview with KUOW and The Seattle Times this week dismissed St. John’s portrayal of what was happening in her unit as “not accurate” and a “gross oversimplification.”

“Sexual assault cases are still being assigned, but the workload is being triaged based on a number of factors that we would traditionally use to triage those cases,” Nollette said.

Nollette emphasized that staffing shortages were being felt across the department. She did not provide an up-to-date count of how many adult sexual assault cases were on hold, although detectives in the unit are keeping a list with dozens of cases.

Other political leaders expressed skepticism at the idea that departmentwide understaffing was to blame for the sexual assault unit’s predicament.

Sponsored

Sen. Manka Dhingra, D-Redmond, a senior deputy King County prosecutor who has led efforts in the Legislature to improve treatment of sexual assault victims, said the sexual assault unit’s problems were about priorities, not adequate staffing.

“I cannot really tell you how pissed I am about this,” Dhingra said. “Because it is completely unacceptable. This is 2022. We should not be having this conversation about allocating resources for survivors.”

A starved sexual assault unit

T

he staffing crisis at the Seattle Police Department is not new.

Sponsored

The department has been losing officers since the beginning of 2020, and staff levels plummeted to a new low at the end of 2021. Whereas 2020 began with 1,290 officers in service, by March 2022 those numbers dropped to 968 — well below the department’s own projections and what the city expected to spend on salaries.

Nollette defended the sexual assault unit’s low staff numbers, saying units across the department felt the impact of the losses. The sexual assault unit wasn’t even the most affected, she said.

“I could bring anybody in here from anywhere in the department and they would tell you the same story,” Nollette said.

Sponsored

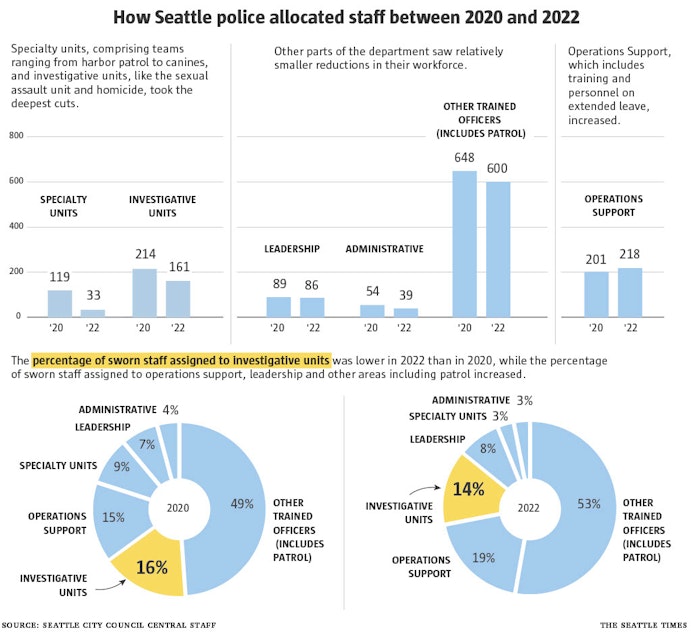

Seattle police staffing numbers presented to the Seattle City Council on April 26 show that the reductions in the workforce have not been felt evenly across the department.

According to council central staff, the percent of the force in operations support — which includes training and personnel on extended leave — and the patrol division has increased while investigative units have thinned. Diaz explained that maintaining patrol numbers wasn’t just important for trying to control 911 response times, but also for taking in reports of rape and sexual assault.

“If we don’t have an officer to respond to sexual assault, we’re never going to have the follow-up to be able to investigate it,” Diaz told the council. “So I’ve tried to make sure we’ve maintained our patrol staffing levels.”

At the top of the department’s priorities for investigating adult sexual assault cases are those with suspects in custody, according to an internal response to St. John’s memo — a small portion of the cases the unit typically sees.

Now, the unit maintains a list of new adult sexual assault cases it’s simply unable to investigate for lack of detectives, according to internal communications at the department obtained by KUOW.

Currently, the sexual assault unit has five detectives to respond to sexual assault and child abuse reports for the entire city, which has had 225 sex offenses reported so far this year, according to the department’s crime data. Yet other units that don’t investigate violent crime have more staff.

The department’s Alternative Response Team — the unit that responds to homeless encampment removals — is now staffed by twice the number of officers on the sexual assault unit after an additional seven patrol officers were added to the unit this year. The department’s general investigations unit, which investigates property crime, has 12 detectives. Far more property crimes are reported to Seattle police each year than sexual assault, but they are simpler to investigate.

“When you have businesses that are the single biggest loss leaders in the country telling you, ‘We are going to close our businesses and leave the city of Seattle’ if we don’t do something about the crime, we have a responsibility as a department to try to do what we can do to support them with policing,” Nollette said.

The department has allowed investigative units, including the sexual assault unit, to fall from 16% of the total sworn force in 2020 to 14% currently, while the proportion of police in areas including patrol, leadership, and operations support has increased.

The understaffing in the sexual assault unit has drained the morale of its employees, most of whom are overworked and burned out, according to a detective in the unit who requested anonymity because SPD policy prohibited them from speaking with the media. While detectives struggle to make a dent in large child abuse and sexual assault caseloads, the department has also drafted them to work security and traffic control at sporting events.

Sgt. St. John wrote the memo after a KUOW story in April that showed Seattle police were investigating few adult sexual assault cases while struggling to meet the demand required by law to quickly resolve cases involving children. St. John declined to comment for this story.

At the time St. John wrote the memo, 30 adult cases were waiting to be assigned to detectives, and 116 alerts showing that identifiable DNA from rape kits had been uploaded to a federal database and needed attention, St. John wrote to Diaz.

The sexual assault unit had historically been staffed with 10 to 12 detectives, St. John wrote, but that the unit could start chipping away at the backlog of adult sexual assault cases with eight.

Mayor Bruce Harrell declined to be interviewed for this story, though mayoral spokesperson Jamie Housen said that a detective had been added to the sexual assault unit this year.

“Mayor Harrell has been unequivocal that SPD needs more officers to ensure specialty units are well staffed so that investigations are completed swiftly and thoroughly,” Housen said by email.

Since St. John’s April 11 memo, detectives have started to receive assignments for new cases with adult victims, but the number of cases that are waiting to be investigated has grown. Even with an added detective, adult assignments are still falling by the wayside, according to the detective inside the sexual assault and child abuse unit.

There are now 48 adult assault cases that aren’t being investigated, according to the detective.

Victims wait, cases suffer

S

ince 2020, King County prosecutors have seen fewer sexual assault cases referred to their office from Seattle police. Between January and April of 2020, Seattle police referred 123 sexual assault and child abuse cases to prosecutors. In the same time period this year, prosecutors have received just 72 cases from Seattle police.

Ben Santos, chair of the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Special Assault Unit, said he’s discussed the problem with St. John. He said on more than one occasion she’s described dozens of cases sitting on her desk, unable to be assigned because of a lack of detectives.

“[Seattle police leaders] are having to make really difficult choices right now, given that homicide and violent crime rates are up,” Santos said. “We have done our best to try and let people know what that means on the sexual assault side — it means that these cases are not being investigated the way they should be.”

He said if detectives are getting assigned a case later than they normally would, it makes it challenging to collect evidence that’s temporary in nature, including surveillance video, third-party witnesses, and physical evidence.

“I really think that to a degree the investigations themselves suffer,” he said.

As do the victims. Santos said he’s received reports that victims who go to Harborview Medical Center for treatment after being sexually assaulted can end up waiting hours to file a report with a Seattle officer.

Increasingly, victims of sexual assault who report their cases to Seattle police aren’t hearing anything back, said Mary Ellen Stone, CEO of the King County Sexual Assault Resource Center.

Seattle’s slowdown in investigating adult rape cases doesn’t match what Stone has seen from other local law enforcement agencies.

“We work with 38 jurisdictions, and while everybody’s dealing with backlogs and everybody’s dealing with staffing shortages, we’re not seeing something similar from other jurisdictions,” Stone said.

Seattle City Council public safety committee chair Lisa Herbold said in an email she had been communicating with advocates who have raised the alarm about victims whose cases are not being investigated, though she was unaware of any policy within Seattle police to stop assigning adult rape cases to detectives.

The police department has planned to add yet another detective to the sexual assault unit this month to deal with caseload and staffing concerns, according to Nollette. But the long-term solution to understaffing in the sexual assault unit was to increase hiring across the department, Nollette said.

To that end, Harrell announced an initiative to increase police hires last month, while last week the council approved a proposal from Herbold to free up more than $1 million in unspent salary savings to fund new police hiring incentives and recruitment.

Advocates have stressed, however, that they’d like to see more transparency in how SPD allocates the resources it already has.

On Tuesday, a man reported to police that he had been raped at knifepoint.

His report was added to the list of stalled cases.

Talk to us

Have you reported a sexual assault to the Seattle Police Department within the last six months? We’d like to hear from you. Get in touch with reporters Ashley Hiruko (hiruko@kuow.org, 206-574-8007) or Sydney Brownstone (sbrownstone@seattletimes.com, 206-464-3225).

Confidential support for survivors

If you have experienced sexual assault and need support, you can call the 24-hour National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline at 800-656-HOPE (800-656-4673). There is also an online chat option. Survivors in King County can call the King County Sexual Assault Resource Center’s 24-hour Resource Line at 888-99-VOICE (888-998-6423) or visit www.kcsarc.org/gethelp.