Seattle is losing more apartments than it's building. Small landlords blame overregulation

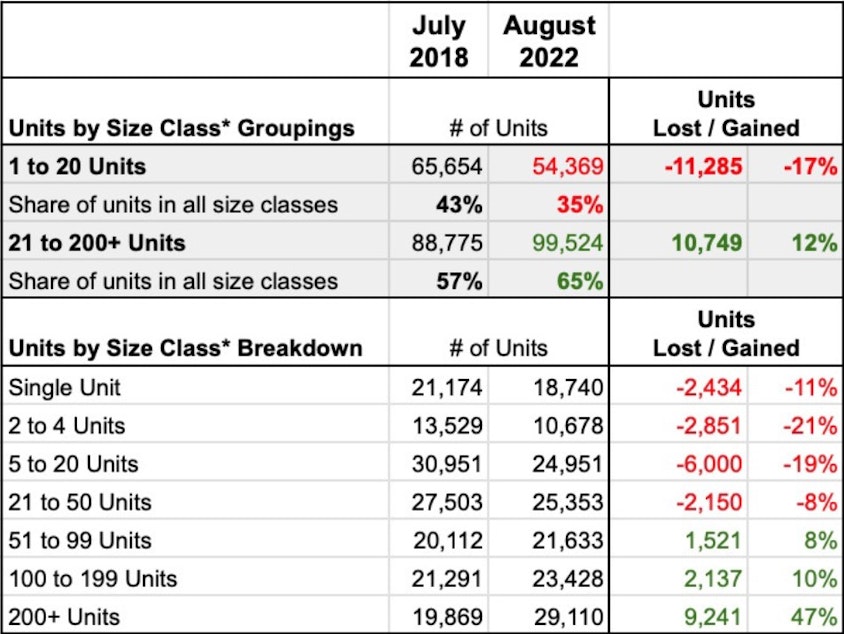

Data from Seattle’s Rental Registration and Inspection database reveal a trend: For every apartment created in a big, new building, a small landlord takes one off the market.

Updated on Monday, 3/27 at 2:16 p.m.: Several listeners have suggested another factor may be responsible for the drop in registered apartments: Landlords may not be complying with the legal requirement to register their apartments. The city has called out this problem, but has not explained whether it's a matter of unfiled paperwork, or due to some of the factors mentioned below, such as demolition for denser housing and sale to owner occupants. If it's paperwork, then the city has a major compliance problem on its hands. KUOW has reached out to the city for clarification, and will update this story accordingly. A full answer may not be attainable until an audit is completed this fall.

Between July 2018 and August 2022, developers in Seattle built nearly 11,000 new apartments in large apartment buildings.

During that same time period, small landlords owning less than 20 units — and many owning just one rental home — were pulling their units off the rental market. More than 11,000 rentable homes owned by small landlords left the market during that period, effectively erasing the gains from large buildings.

Small landlords are more likely to own properties in low-density neighborhoods. Many own so-called "missing middle" housing, such as duplexes and mother-in-law apartments, or they rent out their entire home to long-term renters. Many rent for convenience — perhaps to keep a home while working overseas for a couple years.

When they sell, their homes are not necessarily demolished, though some are to make room for denser forms of housing. Many are purchased and occupied by their new owners.

Nevertheless, the loss of small rental homes in low-density neighborhoods suggests that more and more, renters are being corralled into high-density areas like Seattle's urban villages, while more affluent households can afford to buy in neighborhoods dominated by single family homes.

Sponsored

On Tuesday, March 22, small landlords gathered at the invitation of Seattle City Councilmember Sara Nelson to present their perspective on a wave of recent tenant protections. After presenting these statistics, they warned that updated numbers would look even worse.

“Every small landlord that we know in Seattle has an exit strategy to divest and leave the city,” said MariLyn Yim, a co-founder of the group Seattle Grassroots Landlords.

Ayda Cater, who owns one rental house, said small landlords were "selling to owner occupants and those people are high-earners who can afford to buy. It reduces rental stock, and that is something the city desperately needs."

Small landlords blame excessive regulations for driving so many of their peers to sell. Yim cited well over a dozen permanent tenant protections enacted by Seattle and Washington state since 2020.

Sponsored

T

enant protections were put in place amid the pandemic because so many renters are hurting. The tension renters face when trying to resolve mounting fines can create tremendous strain for a tenant, especially around the time a household approaches the crisis point of being evicted.

Tenant advocates like Edmund Witter of the King County Bar Association's Housing Justice Project consider the recent wave of tenant protection laws a success. He told KUOW that in 2022, "Evictions were only 44% of what they were before Covid. Statewide, they're about half what they were before the pandemic."

At Wednesday's round table, small landlords acknowledged the strain tenants feel. But they noted that they too are strained by regulations which they say negate their profits and can make normal communications with tenants feel as stressful as a courtroom proceeding.

The circumstances surrounding a Ballard renter who died by suicide as law enforcement attempted to evict her on Monday also came up. A sheriff's deputy was shot during the confrontation and was taken to the hospital with critical injuries, but has been stabilized.

Sponsored

KOMO News reported that the Ballard tenant owed about $13,000 in rent and had exhausted her rental assistance options, according to an unnamed friend. An unnamed neighbor told KOMO the tenant didn't want to be homeless again.

At City Hall, small housing provider Ayda Cater described an incident with her only tenant in which she accumulated over $100,000 in costs during the eviction moratorium and narrowly avoided a violent encounter. Her story prompted Councilmember Dan Strauss to respond, "I’m really sorry that that was your situation with your home that you bought, rented, and beyond the damage that occurred — when firearms are involved, it just makes it very scary.”

After hearing these stories, Councilmember Sara Nelson said, "We do have to think in the long-term about the most vulnerable people here, and they're not the property owners — they're the renters." But she added that she wanted small landlords to be invited to future policy discussions about regulations, and promised to keep the door open to their concerns.

I

n 2018, the last time they were polled on this and before the wave of new regulations began taking effect, 59% of small landlords reported earning less than $75,000 per year — including income from rentals and their jobs.

Sponsored

They say larger landlords — especially those whose buildings include over 50 units — are much more able to spread risk around, diluting among many people the cost of responding to individual tenant needs.

In response to those findings, the small landlords are asking for reforms, such as designating some branch of city government to hear and respond to landlord concerns.

Ironically, the data the small landlords brought to the council comes from another landlord regulation that rolled out in waves between 2013 and 2016: the Rental Registration and Inspection Ordinance. That database tracks apartments and their owners to ensure rental homes are adequately maintained.

For the purposes of their presentation, the small landlords reformatted the data to demonstrate trends more clearly, but left the source numbers unchanged.

Councilmember Lisa Herbold presented a conflicting perspective, suggesting better data was available from an earlier study. That study showed a rise in the number of rental apartments available. Landlords said the study Herbold cited wasn't current enough to reflect recent regulatory changes.

Sponsored

In reporting on tenant/landlord relations, there's a risk reporters must guard against: letting anecdotes from small landlords point the way towards policy. Legitimate stories of small landlord hardship have been used historically to shape public opinion against the regulation of all landlords, including large ones.

But the numbers also reveal how statistically significant these small landlords are. In 2018, they had 43% of the rental market. In 2022, that market share had dropped to 35%, with the largest losses of housing being small, middle housing apartments like backyard cottages and duplexes.

RELATED: Backyard cottages take off in Seattle. But who benefits?

It can be difficult in complex markets to draw a straight line between a result like that and its cause. After all, other market forces are also at play, including a severe shortage of affordable homes for people to buy and a ban on new mega-mansions, which could inspire wealthy buyers to purchase a duplex and convert it to a larger single home.

Concentration of Seattle's housing growth in "urban villages" all but ensures "naturally affordable" older homes within those economic blast zones will be torn down and redeveloped, a trend that backers of "middle housing" legislation in Olympia hope to reverse by releasing the pressure valve and allowing such housing everywhere.

But whatever its origin story, one trend has become quite clear: Seattle's landlord scene has become distinctly less "mom and pop" and a lot more corporate.