Feds push for dirtier waters. Tribes say that threatens their health

Washington tribes and state officials say the Trump administration is breaking the law and endangering public health with an Environmental Protection Agency proposal to allow more pollution in Washington waters and Washington fish.

Tribal leaders from around the state told EPA officials at a hearing at the agency’s regional headquarters in Seattle on Wednesday that the proposed rollback of regulations on 99 different water pollutants violated their treaty rights by making fish dangerous to eat.

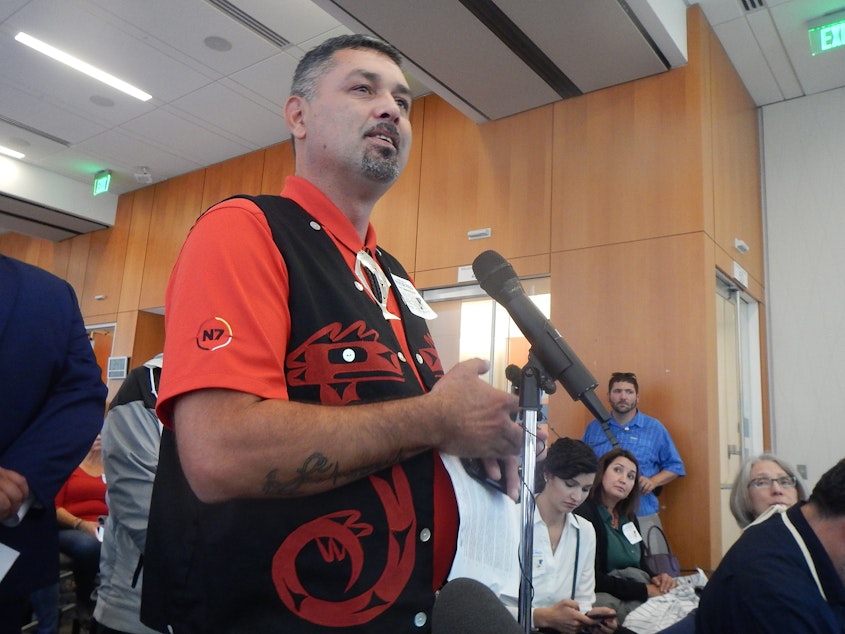

“This is scary for me because of the amount of fish my people eat,” Patrick Depoe of the Makah Tribal council said.

With tribes relying heavily on salmon and other seafood, they are affected more than most by the longstanding tussle over the regulation of 99 different pollutants in Washington state waters.

The arcane-sounding regulations under section 304 (a) of the federal Clean Water Act allow different concentrations of each pollutant, with the goal of limiting cancer risk to one in a million by assuming that people eat 175 grams of fish a day.

“I don’t what the heck a gram is,” Puyallup elder Nancy Shippentower said. “We take a big piece of fish and we eat it. We can it, we smoke it, we save it. Our children grow up like that.”

Sponsored

Many tribal members and other Washingtonians eat more fish than state and federal regulations assume.

“If you see this little 2-year-old girl in here and you think it’s okay for that child to eat so many cancer-causing chemicals, this is wrong. Any parent knows this is wrong,” Lydia Sigo, a museum archivist and geoduck diver with the Suquamish tribe, said. “You have no idea how much fish and clams we eat every single week, and we do this knowing that we are eating PCBs, and we still do it because it’s part of our religion."

Washington tribes gave up most of their land in exchange for the right to keep fishing and hunting.

“Exercising those treaty rights should not put our communities at a disproportionate risk of cancer,” Depoe said.

Depoe and other tribal leaders said the EPA failed to undertake government-to-government consultations with the tribes, in violation of treaties between the tribes and the United States.

Sponsored

Among other changes, the EPA is proposing to quadruple the acceptable amount of dioxin in the water and increase the limit on PCBs 20-fold.

EPA officials said little after the agency’s Sara Hisel-McCoy read aloud a series of slides laying out the background of the current proposal.

“We’re here to listen,” said EPA Deputy Assistant Administrator Lee Forsgren, the political appointee in charge of water safety at the agency. He came to the EPA in 2017 after being an attorney for a fossil-fuel lobbying firm.

The EPA proposal is in response to a petition by the Northwest Pulp and Paper Association and other industry groups.

Chris McCabe with the pulp and paper association said current water quality standards “cannot be achieved with existing or even foreseeable technology.”

Sponsored

“Unachievable standards of any type, for water quality or anything, do not drive meaningful environmental protection,” McCabe said. “Instead, they result in permitting chaos, uncertainty and litigation.”

Oregon Department of Environmental Quality director Richard Whitman said similar regulations in his state had been in place for more than a decade and had proven successful in other states as well.

“EPA is dead set on systematically dismantling clean water protections and states’ rights,” Washington Department of Ecology director Maia Bellon said. “To this, Washington state says, ‘no.’”

Bellon said this was the state’s 8th formal communication opposing EPA’s “regressive and illegal” proposal. Washington Attorney General Bob Ferguson sued the EPA over it in June.

The EPA is taking public comment on the proposal until Oct. 7.