Pacific Northwest’s busiest volcano predicted to erupt by end of 2025

Don’t be too hard on yourself if you’ve never heard of the Northwest’s most active volcano.

It has no national park or ski area named after it. Its heights grace no city’s skyline.

The Axial Seamount is a mile underwater and nearly 300 miles out to sea.

It has erupted three times since 1998, and researchers predict this remote but closely monitored deep-sea mountain will do so again in 2025.

Researchers from Oregon State University, the University of Washington, and the University of North Carolina at Wilmington presented their volcano forecast at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in December in Washington, D.C.

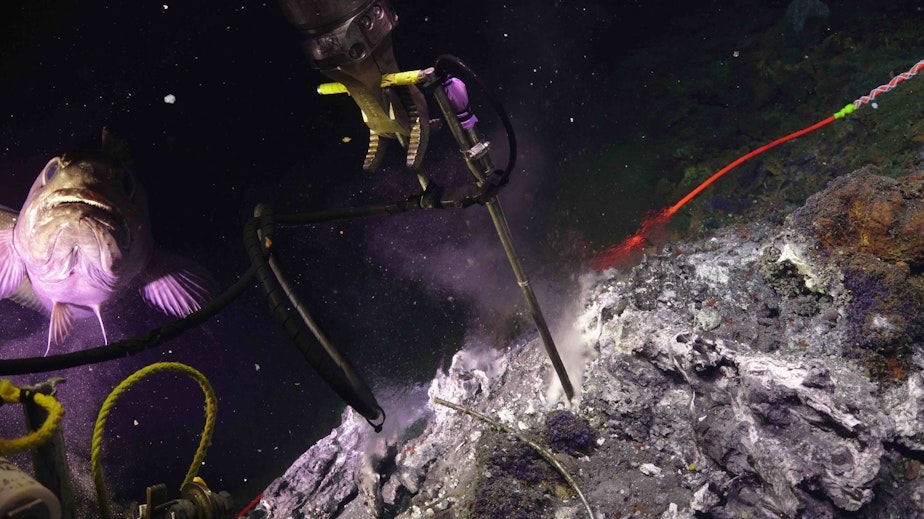

Thanks to a dense array of sensors on the volcano’s summit and flanks, scientists know that Axial Seamount has been swelling with magma and getting taller, a sign that it’s ready to go off.

Sponsored

Pressure sensors on the seamount show that the summit has bulged about 10 feet closer to sea level than its depth after the last eruption in 2015.

“It's at a point where it could erupt now, based on that prediction,” said University of Washington geophysicist William Wilcock.

Any Axial eruption would not pose any risk to humans — or the global atmosphere.

“It does this a lot,” geophysicist Michael Poland said of Axial’s eruptions. “People don't notice.”

Poland is with the U.S. Geological Survey’s Cascades Volcano Observatory in Vancouver, Washington.

Sponsored

He said Axial’s location, a mile underwater and 280 miles west of the mouth of the Columbia River, and an equal distance southwest of Canada’s Vancouver Island, insulates humans from harm.

“Fortunately, it's not dangerous,” he said. “It's very, very deep, and these deep-water volcanoes don't tend to have huge effects.”

By contrast, an eruption from a shallow underwater volcano in the South Pacific nation of Tonga in Jan. 2022 sent a tsunami and sonic boom circling the globe as well as unprecedented volumes of water and aerosols into the Earth’s stratosphere. A team of researchers recently concluded that the water vapor and tiny rock particles from that single explosive event had blocked enough sunlight to slightly cool the entire Southern Hemisphere for nearly two years.

Wilcock said any pockets of steam rising from the mile-deep Axial Seamount would very quickly cool in the ocean depths and collapse, causing implosions that can be picked up by underwater microphones as well as seismographs.

Those implosions mostly cause rumblings at frequencies too low to be detected by human ears. But you can hear the Axial Seamount erupting on the ocean floor off the Washington and Oregon coasts in 2015 in this recording, shared by Wilcock after speeding it up 50-fold to audible frequencies:

Sponsored

Axial Seamount's 2015 eruption

Axial Seamount erupts on April 23, 2015, in a recording sped up 50x, to frequencies audible by humans. Courtesy William Wilcock, University of Washington.

The volcano has also started rumbling much more frequently in 2024 — with about 100 to 200 small earthquakes a day, though it has not reached the daily 1,000 quakes that shook the seafloor before Axial’s 2015 eruption.

“So I'm not sure it will erupt in the next year, maybe a couple of years, but we'll find out,” Wilcock said.

The volcano is constantly monitored by a network of sensors on the seafloor. They are connected by a cable that runs 300 miles back to Pacific City, Oregon.

Poland, who was not involved in the eruption prediction, said researchers had accurately predicted Axial Seamount’s 2011 and 2015 eruptions.