Ongoing rise in fentanyl deaths highlights need for treatment alternatives

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid intended for pain management. It's 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine. In King County's most recent annual overdose death report, fentanyl is named as the biggest driver in those deaths, which continue to spike.

Caleb Banta-Green tracks these numbers and advocates for possible solutions. He's an acting professor at the University of Washington's Addictions, Drug & Alcohol Institute, and the principal investigator in the institute's research study of low-barrier, community-based access to opioid addiction care. He also serves on the Washington state substance use recovery services advisory committee. He talked to KUOW’s Kim Malcolm about overdose deaths and treatment advances.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Kim Malcolm: King County's latest report is showing that the number of these deaths in the first three quarters of this year are already more than last year's totals. What does this tell you?

Caleb Banta-Green: It's really devastating for people working in the field, and for family, friends, and communities. It's really stunning, the numbers we're seeing. I haven't seen anything like it in my 27 years of working with folks with opioid addiction and people experiencing overdoses. It tells us that, obviously, there are a lot of folks using these substances, clearly. And it's such a lethal, lethal drug, that it's causing all of these overdose deaths.

What is driving these increases year over year?

Part of it is we always have folks who have an opiate addiction, who are not in some sort of effective treatment. They're out there using. There are new folks coming in, often young adults, and the challenge in particular now is we have this new substance. Heroin is a product that really had to be injected. These fentanyl fake pills, and sometimes powders, don't have to be injected. They can be smoked, or even swallowed, or snorted. So, the barrier to entry is much, much lower. And the substances are just inherently much more dangerous, and much more addictive.

Sponsored

What stands out to you about who is dying?

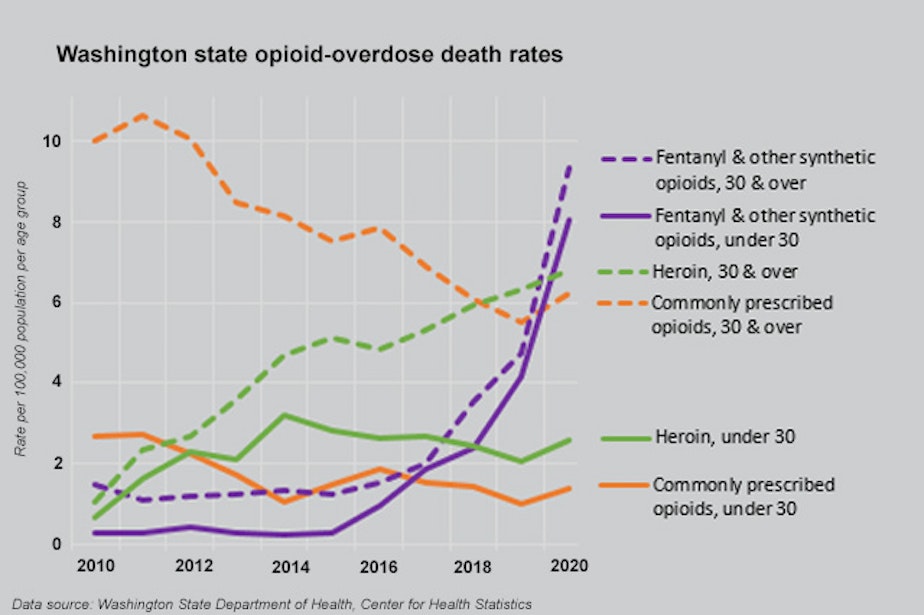

With both heroin and prescription-type opiates, generally, the overdose death rate is much higher for older adults than it is for younger adults. We don't see that with fentanyl. They're actually really, really similar. That is, the death rate is almost the same for those under 30, as for those over 30. These are really often young folks who may not even have an opiate addiction, or early on in their addiction and dying really just far, far too young.

Your op-ed for the Seattle Times this week seemed to indicate that there may be more hope now for treating people than there has been in the past. How so?

We've been working for almost six years now to create community-based care access points, mostly setting up places for people to start on life-saving opioid addiction treatment medications. That's where I get so much of my positive reinforcement, from those programs, and those staff. What they're saying is that this is the model of care they’ve been waiting for. People are coming in, and they’re thriving and doing well. What we're really advocating for and hoping for is a dramatic expansion of that model, from the roughly half dozen programs in the state, to really making it a statewide model.

Is there a story you refer people to when they’re overwhelmed by these waves of deaths that come from this kind of substance use disorder?

Sponsored

One of the real signs of optimism to me was early on in our research when we heard from one of our staff out in the community that an older woman had come in. She had a long history of opioid addiction. She looked near death when they first met her. A couple of weeks later, she was coming back. She was on treatment medication. She was doing really well, and she said to them, "You were the first people that have ever treated me well, and I've brought in a handful of my friends to get started in your program as well."

The vast majority of people want care, and we should want and demand that care in our community. We will need people to be demanding that care, not fearful of it, not fighting it, but in fact demanding it and wanting it in their communities.

Listen to the broadcast interview by clicking the play button above, and to the extended version below.