Bubble hunters: Ocean scientists count 1,000 methane seeps off Pacific Northwest coast

Ocean researchers have found nearly 1,000 methane seep sites along the continental shelf of the Pacific Northwest. The bubble streams could be a sign of offshore energy potential, represent a greenhouse gas threat — or be neither of those things at all.

Oregon State University geophysicist Bob Embley said the discovery is "eye-opening" on many levels. Previously, researchers had only documented 200 methane seeps off the Pacific Northwest Coast.

"Methane is a greenhouse gas," Embley said during a public radio interview with members of the joint OSU/NOAA team in Newport, Oregon. "We don't know how much, if any, is getting to the surface and into the atmosphere from the ocean."

So far, researchers are finding that most of the methane dissolves into the water column before it reaches the surface. Initial chemical analysis of the bubble streams points to organic matter that fell to the seabed and decayed, rather than a sign of possible oil and gas reserves deep below.

"I don't think it's anything valuable," the team's chemistry expert, Tamara Baumberger, said when asked if the methane bubble streams could indicate offshore energy potential for the Pacific Northwest coast.

But one concern among scientists is that the seafloor could potentially release more methane as the ocean slowly warms due to climate change. Methane is a far more potent greenhouse gas than the better known carbon dioxide.

First, the team has to map out how much methane release is normal for the seafloor.

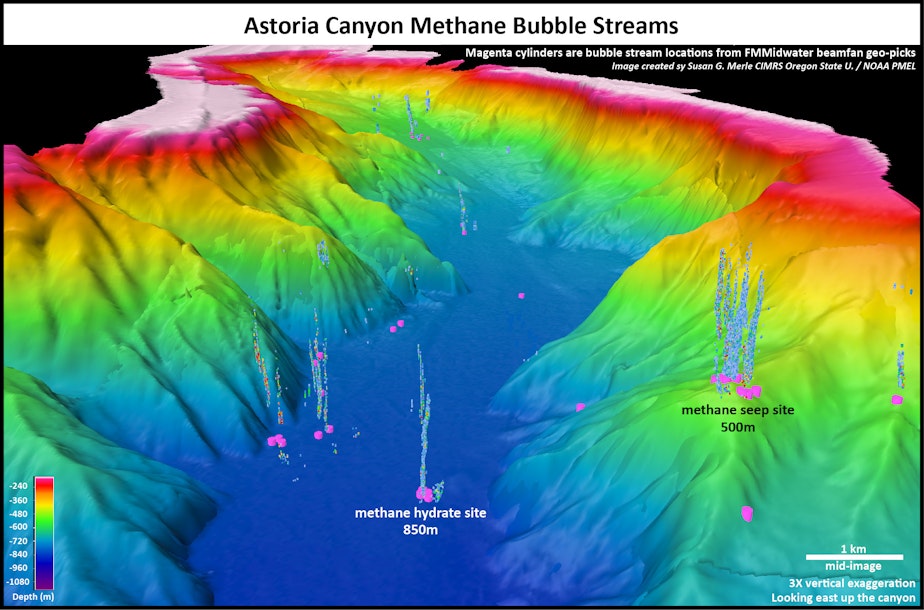

When the project started, oceanographers knew of roughly 200 methane seep sites along the Cascadia Margin. Over the course of 10 expeditions since, they've found 800 more. Advances in sonar technology made it possible to efficiently survey for bubble streams using an instrument on a ship that swept the ocean floor.

The number of seep sites jumps after every survey cruise, now totaling ten expeditions over the past three years, OSU oceanographer Susan Merle said. Merle's database is approaching 1,000 sites, encompassing more than 2,700 discrete methane bubble streams, and that's a number bound to climb even higher.

"We've only mapped about 40 percent of the Cascadia Margin," Merle said. "Most of that mapping has been in deeper water."

Seafloor methane originally drew interest when submersibles photographed a solid, ice-like form called methane hydrate in deep, cold waters. There has been off-and-on interest in the study of seafloor methane since — mostly from Asian energy exploration companies as a potential gas resource. Still, the mining and extraction has proved to be extremely difficult.

The OSU/NOAA team saw hydrate formations during ROV dives from the R/V Nautilus expedition in June and even retrieved a few samples from the seafloor. Funding for the project comes from the NOAA Ocean Exploration and Research Program, while researchers are based at a joint OSU/NOAA laboratory at the Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport, Oregon.

The video camera on the ROV also showed how some of the methane seeps create oases on the seafloor. There, methane-eating bacteria support the base of a food chain that includes sea worms, clams, and fish in profusion.

On both a 2016 and a 2018 cruise, the researchers dropped a sensitive underwater microphone on the seabed next to a methane seep off the coast of Oregon.

NOAA acoustics scientist Bob Dziak said the hydrophone was deployed for short periods as a "proof of concept" to show how a passive acoustic tool could be used to monitor and quantify the gas flux. The rising bubbles made a distinct sound like "crackling bacon" or rain on a metal roof, he said.

"Ultimately, my goal is to use the records to make an estimate of the volume of gas coming out," Dziak said in an interview this month.

Results of Dziak's 2016 hydrophone experiment were published this spring in the journal Deep-Sea Research II.

[Copyright 2018 Northwest News Network]

The number of seep sites jumps after every survey cruise, now totaling ten expeditions over the past three years, OSU oceanographer Susan Merle said. Merle's database is approaching 1,000 sites, encompassing more than 2,700 discrete methane bubble streams, and that's a number bound to climb even higher.

"We've only mapped about 40 percent of the Cascadia Margin," Merle said. "Most of that mapping has been in deeper water."

Seafloor methane originally drew interest when submersibles photographed a solid, ice-like form called methane hydrate in deep, cold waters. There has been off-and-on interest in the study of seafloor methane since — mostly from Asian energy exploration companies as a potential gas resource. Still, the mining and extraction has proved to be extremely difficult.

The OSU/NOAA team saw hydrate formations during ROV dives from the R/V Nautilus expedition in June and even retrieved a few samples from the seafloor. Funding for the project comes from the NOAA Ocean Exploration and Research Program, while researchers are based at a joint OSU/NOAA laboratory at the Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport, Oregon.

The video camera on the ROV also showed how some of the methane seeps create oases on the seafloor. There, methane-eating bacteria support the base of a food chain that includes sea worms, clams, and fish in profusion.

On both a 2016 and a 2018 cruise, the researchers dropped a sensitive underwater microphone on the seabed next to a methane seep off the coast of Oregon.

NOAA acoustics scientist Bob Dziak said the hydrophone was deployed for short periods as a "proof of concept" to show how a passive acoustic tool could be used to monitor and quantify the gas flux. The rising bubbles made a distinct sound like "crackling bacon" or rain on a metal roof, he said.

"Ultimately, my goal is to use the records to make an estimate of the volume of gas coming out," Dziak said in an interview this month.

Results of Dziak's 2016 hydrophone experiment were published this spring in the journal Deep-Sea Research II.

[Copyright 2018 Northwest News Network]

The video camera on the ROV also showed how some of the methane seeps create oases on the seafloor. There, methane-eating bacteria support the base of a food chain that includes sea worms, clams, and fish in profusion.

On both a 2016 and a 2018 cruise, the researchers dropped a sensitive underwater microphone on the seabed next to a methane seep off the coast of Oregon.

NOAA acoustics scientist Bob Dziak said the hydrophone was deployed for short periods as a "proof of concept" to show how a passive acoustic tool could be used to monitor and quantify the gas flux. The rising bubbles made a distinct sound like "crackling bacon" or rain on a metal roof, he said.

"Ultimately, my goal is to use the records to make an estimate of the volume of gas coming out," Dziak said in an interview this month.

Results of Dziak's 2016 hydrophone experiment were published this spring in the journal Deep-Sea Research II.

[Copyright 2018 Northwest News Network]