Ocean heat wave comes to Pacific Northwest shores

An ocean heat wave has come ashore in the Pacific Northwest.

While the world’s oceans have been hitting record temperatures in 2023, Northwest coastal waters have, until recent weeks, remained cooler than their long-term average.

Now the Pacific Northwest has joined the rest of the world in having exceptional ocean heat.

Strong upwellings of cool water from the depths kept an offshore blob of exceptionally warm water in the northern Pacific Ocean from nearing the west coast of North America this spring.

That big blob of warm water in the middle of the Pacific Ocean grew steadily until reaching the Oregon and Washington coasts in July.

Sponsored

“This thing is covering most of the Northeast Pacific,” said Andrew Leising, an oceanographer at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration in La Jolla, California.

Satellite imagery and scientific buoys that monitor real-time conditions far from land detected the change.

Sea surface temperatures inside this blob are 5 to 7 degrees Fahrenheit above average.

“That's not normal, by a far stretch,” said University of Washington oceanographer Jan Newton, who runs a network of automated observatories off the Northwest coast. “We should definitely be concerned.”

Sponsored

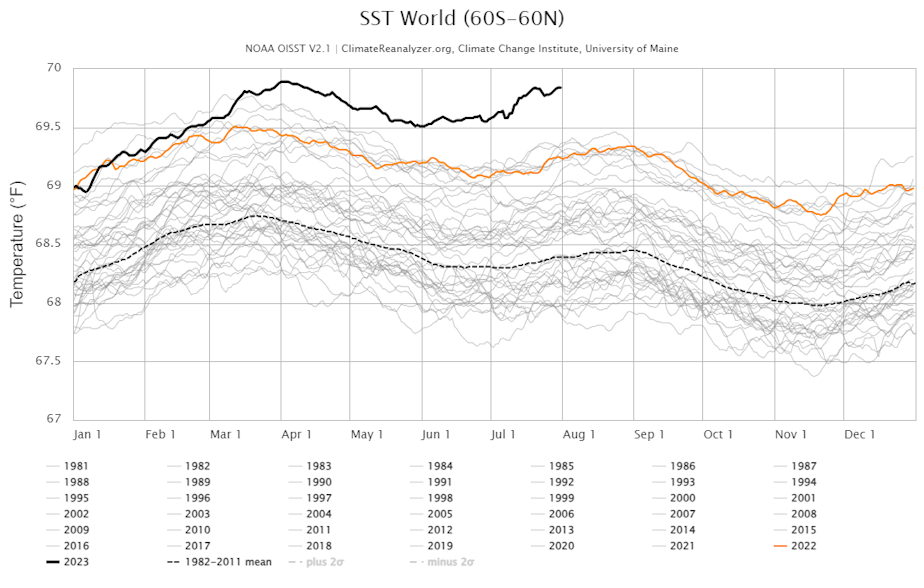

Globally, oceans have hit record temperatures in 2023, with the surface of the world’s seas in April nearing an average of 70 degrees Fahrenheit, according to the University of Maine’s Climate Change Institute. Waters off Florida have reached freakish, bathtub-like temperatures, while seas from Japan to Greece have been hit by marine heat waves, and Antarctic ice has hit record-shattering lows, covering far less ocean than normal for the southern hemisphere winter.

“For us on the West Coast, we're not reaching record-breaking temperatures, but we're closing in on them,” Leising said. “It's kind of expected because we know the oceans have been warming at a slow but steady rate for decades now.”

With carbon dioxide and other greenhouse-gas pollutants trapping more of the sun’s heat, we shouldn’t be surprised as temperatures head into uncharted territory, on land and at sea.

“We're going to just keep seeing, year after year, breaking record, breaking record, breaking record,” Leising said.

Sponsored

A key question for the ocean heat wave now on the West Coast is whether it will stick around long enough to damage the food chain that creatures like seabirds, salmon, and humans rely on, as an extreme Pacific Ocean heat wave dubbed "The Blob" did in 2014 and 2015.

“In the Pacific Northwest, a lot of our organisms are used to pretty variable conditions because we have the upwelling/downwelling, where temperatures change rapidly according to the winds,” Newton said. “But at some point, you can exceed tolerances.”

Newton said much sea life is more sensitive to temperature changes than warm-blooded, land-based creatures.

“For humans, our air is warmer during the day, and it cools off at night, whereas an aquatic organism is in that [extra-warm] water all the time,” she said.

“A lot of animals will just have a hard time. Even if the heat didn't bother them, they'll be bothered by not having food around,” Leising said.

Sponsored

Not all organisms fare worse in a heat wave, though.

Harmful, toxin-producing algae can thrive in warmer water, leading to impacts on other species and fisheries, as happened during a marine heat wave in 2022.

“First it was razor clams, then it was mussels, then it was Dungeness [crabs]. So we had a series of shellfish closures all through the fall,” Leising said.

The sea surface along the Northwest coast usually hits its peak temperatures in mid- to late August, according to Leising.

Sponsored

In recent years, Pacific Ocean heat waves — defined by how much they deviate from normal, rather than absolute temperature values — have lasted into mid-December, Leising said.

The impact of this heat wave could be amplified by the arrival of the climate phenomenon known as El Niño, which leads to warmer water in much of the Pacific Ocean. In June, National Weather Service forecasters announced that El Niño conditions had developed off the west coast of south America, reversing three years in a row of the opposite, La Niña conditions.

El Niños generally have little influence on the United States until late autumn.

“El Niño is happening. But it's right now just limited to the equator region,” Leising said.

El Niño conditions this far north, on top of a persistent marine heat wave, could be a double whammy, leading to more record ocean temperatures, higher storm surges, and other impacts. Water expands as it warms, raising sea levels as it does.

Washington state climatologist Nick Bond said marine heat waves tilt the odds in favor of warmer weather on land in the Northwest.

“The meager snowpack of the winter of 2014-15 can be attributed in part to the extremely warm ocean temperatures that prevailed during the heyday of the "Blob," Bond said by email. “We do not want that to happen again.”

In July, the National Weather Service put the odds at more than 90% that El Niño will continue through the Northern Hemisphere winter.