New highways headed to Seattle area despite drive to fight climate change

Even as Washington state tries to clamp down on climate-harming pollution, it’s building new highways in its two biggest counties.

Transportation is a vital link for any economy. In Washington state and nationwide, it’s also the largest source of the pollution that is destabilizing the planet’s climate.

On March 25, Gov. Jay Inslee approved spending $16.9 billion on transportation, from the most-polluting to the least-polluting ways of getting around.

Over the next 16 years, $4.2 billion is slated for widening or building new highways in the state, including one in Jacquelyn Harris’ neighborhood.

Every morning, Harris walks laps around her apartment complex in Fife for a bit of exercise.

Sponsored

“I have my earbuds in, listening to my music, and I can barely hear the music when I'm going down that side, which is adjacent to the freeway,” she said.

Highway noise and exhaust from Interstate 5 are facts of life for people living in the apartment complex owned by the Pierce County Housing Authority.

“I mean, you can smell it, you can see it. The pollution, the exhaust from the vehicles,” Harris said.

Harris says relentless construction on I-5 in Fife and neighboring Tacoma means more noise and pollution for its neighbors.

“It seems like there's always a project going on,” Harris said.

Sponsored

“More consideration should be given to the residents of the adjacent neighborhoods for that construction, especially when they're closing exits and then rerouting folks through neighborhoods,” she said.

Six brand-new miles of state Route 167 are in the works for Fife, Puyallup, and Tacoma to connect that highway to Interstate 5.

The new highway is part of a $2.4 billion megaproject called the Puget Sound Gateway, newly funded by the state Legislature.

Together with a new segment of state Route 509 south of Sea-Tac Airport, it adds up to 8 miles of brand-new highway between Sea-Tac and Puyallup. The project will also widen about 4 miles of I-5.

But it may bring more pollution to communities like Harris'. It also highlights the tension that exists for elected officials who want to both provide key infrastructure and reduce climate-harming emissions.

Sponsored

K

ristin Kershaw with Superfresh Growers in Yakima says she’s excited about the Puget Sound Gateway.

“We export about 25–30% of our apple crop and even more of our cherry crop,” Kershaw said. “So access to ports and air cargo — it’s really important.”

During the Covid pandemic, Kershaw says, traffic congestion hasn’t been the biggest problem for the supply chain, but it’s still a big one.

Sponsored

“It's no fun to be a truck driver sitting and waiting for hours to be able to get your product unloaded, either because you're stuck in traffic or because you can't get unloaded at the port,” Kershaw said. “That's money that you're not making.”

She expects the new highways will make a big dent in congestion heading to the ports of Seattle and Tacoma.

The Washington State Department of Transportation predicts the tonnage of freight moved by truck in Washington state will grow 35% by 2035.

According to WSDOT, Tacoma has the state’s highest daily truck traffic.

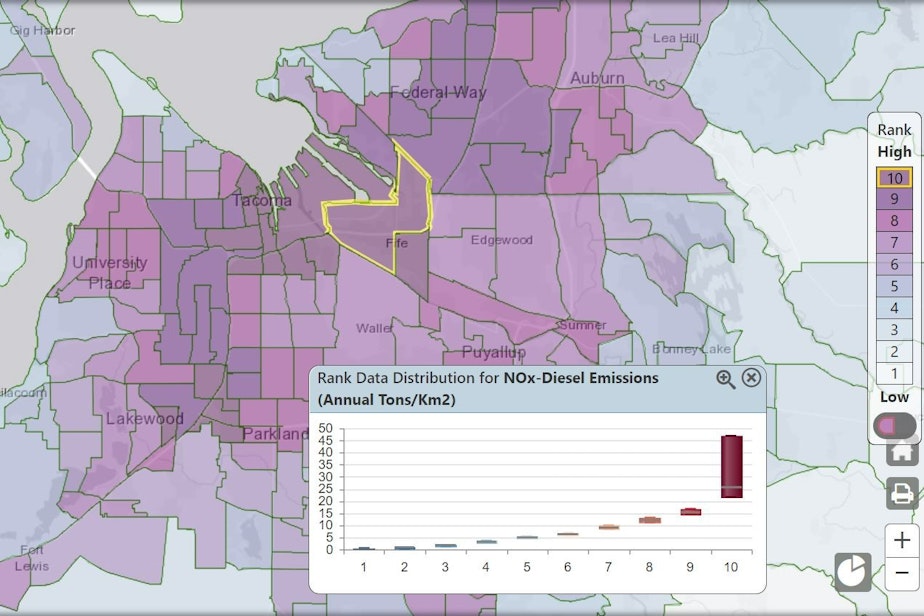

Harris’ census district in Fife and neighboring areas near the Port of Tacoma have some of the state’s worst diesel pollution, according to the Washington Environmental Health Disparities Map, produced by the University of Washington and a consortium of government and non-profit groups.

Sponsored

“I think we would all love to have had electric trucks yesterday,” Kershaw said. “But that doesn't seem to be happening anytime really soon.”

In 2021, electric vehicles, including “plug-in hybrids” that can run on either battery power or gasoline, were just 1.3% of all passenger vehicles in Washington, with almost no electric trucks on the roads.

Kershaw says until electric trucks are widely available, the best way to reduce truck pollution is to build better roads.

“Because then we can get those trucks in and off the road quickly,” she said.

T

ransportation officials often claim that their highway projects will reduce congestion and pollution.

“In drawing traffic away from the local [road] network, we reduce congestion in the region in and around the new expressways and provide much more efficient travel,” said John White, who heads the Puget Sound Gateway program for the state’s transportation department. “So there's less idling for the trucks, less idling for the cars.”

White says the new highways will lead to less, not more, driving by providing more-direct routes that will let truckers avoid zigzagging along city street grids.

Such claims go against a widely accepted concept in transportation planning called “induced demand”: More lanes lead to more driving and all the impacts that come with that.

“Traffic is kind of like a gas, if you remember your physics,” pedestrian advocate and ex-Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn told the “Hacks and Wonks” podcast. “It expands to fill the room available to it.”

In other words: Build it and they will come.

“Induced demand is a fact,” Washington Transportation Secretary Roger Millar said when I interviewed him in 2021. He’s John White’s boss’s boss’s boss.

“We're not going to build our way out of our congestion problem,” Millar said. “What we need to do is manage congestion and give people alternatives to getting around.”

Millar said widening highways should be the last thing his agency does, but that’s not his call.

“There are two things I don't do as secretary of transportation,” Millar said. “I don't appropriate money and I don't make policy.”

I asked transportation researcher Mark Hallenbeck at the University of Washington if congestion relief is a false promise.

“Sure! Of course it is. That’s been known for 50 years,” Hallenbeck said. “Yes, the car is a wonderful thing. It’s just a space hog.”

B

rand-new highway construction is rare in 21st-century America. The heyday of U.S. highway building was 50 to 70 years ago.

Transportation officials say highways 167 and 509 are critical freight corridors for the ports and warehouse districts of a rapidly growing region. Their unbuilt segments are “missing links” from when the highways were planned and built in the 1970s.

McGinn said completing 509’s missing link would have unintended consequences for south Seattle.

“If you think the backups at the First Avenue South Bridge are bad now, wait ‘til you see what it’s like when you basically are mainlining cars from I-5 to the west of Sea-Tac Airport straight to the First Avenue Bridge,” McGinn said. “And who’s going to breathe all the pollution of those idling cars? Residents of South Park and Georgetown and the Duwamish Valley.”

Unlike in the 1970s, our overheating climate has become an urgent, life-or-death concern in the 21st century. So have the health needs of poor communities of color that often live near highways and their unhealthy air.

“Why would we sign up for 15 more years of emissions from our largest sector, right?” asked climate-justice activist Paulo Nunes-Ueno with the group Front and Centered.

“We need to stop asking the same communities to pay the price again, and again, for our failure to move away from autos and oil,” he said.

“What's important is to make sure that we're not baking in more carbon emissions with our decisions now,” said Ben Holland with the Rocky Mountain Institute.

The Colorado-based energy think tank worked with researchers at the University of California Davis to produce an “induced demand” calculator to estimate how much traffic or pollution highway projects will generate.

The Rocky Mountain Institute calculator predicts the Puget Sound Gateway will lead to at least 60 million additional vehicle miles of driving annually. Over the next two decades, WSDOT forecasts a 30% increase in driving nearby, which it says the Puget Sound Gateway will lower by two percentage points.

WSDOT officials say demand to use the Puget Sound Gateway highway segments will be dampened by round-the-clock tolling, though toll amounts have not been set. The officials also say at least 1.5% of the project's total cost will go to building bike paths and sidewalks, which could help entice people out of their cars altogether.

W

ith the new transportation package that is funding the Puget Sound Gateway, Washington state is pouring billions into climate-friendly transportation as well as highways over the next 16 years.

It’s a big shift from the highway-centric spending of the past.

“This is another step forward in revolutionizing our transportation system,” Gov. Jay Inslee said.

He called the package “the biggest, the boldest, the cleanest and the greenest transportation and climate project in the history of the state of Washington.”

Still, critics say the climate can’t wait another decade or more for Washington to get off its highway-expansion treadmill.

“We're at this critical juncture in ensuring that we reduce transportation emissions as quickly as possible,” Holland said.

On Monday, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the world’s foremost scientific body on the climate, released another big report highlighting the urgency of deep emissions cuts in all areas of the economy to limit the destruction expected with a rapidly heating world.

"It's now or never," said report co-author Jim Skea of Imperial College London. "Without immediate and deep emissions reductions across all sectors, it will be impossible. "

Washington Democrats who passed the big transportation package in March are calling it “climate-oriented” since it includes more money for mass transit and human-powered travel ($6 billion) than expanding highways ($4.2 billion). Another $3 billion would go to preserving and maintaining existing highways and $2.4 billion to fixing the culverts beneath them that block salmon from reaching spawning grounds.

The mix of spending split environmental activists and caused heartburn within the Democratic Party.

“Why is the state still funding new state highway lanes, even though we know they increase global warming emissions and we know they do not reduce congestion?” Democratic Party activist Will Affleck-Asch asked legislators at a meeting of the 43rd District Democrats.

“I really agonized back and forth over voting for the transportation package for the reasons you state,” Rep. Nicole Macri of Seattle replied.

“It is the best package we have ever seen in the history of the state, and as you point out, it is not perfect,” she said. “We definitely need to be looking at alternatives to highway expansion.”

In response to Affleck-Asch’s question, Sen. Jamie Pedersen of Seattle said political calculus was a key factor.

“We are going into an absolute perilous year for Democrats,” he said. “It’s not at all out of the question we could lose the House this fall. Getting a transportation package done is probably one of the most important positive things we could do for retaining control of the legislature.”

Republicans opposed the transportation package because the legislature-dominating Democrats gave them no opportunity to help shape it.

“For the first time in our history, a completely partisan transportation package has been passed with zero input from 20 Washington state legislative districts,” Republican Sen. Curtis King of Yakima said in a press release.