Searching for climate and inequity hot spots, by car

Fifteen cars with blue snorkels jutting up from their passenger windows drove around King County on Monday, the hottest day the Seattle area has seen in 2020.

Volunteer drivers crisscrossed roads from Shoreline to Enumclaw. Their odd window attachments were used to record temperature and humidity measurements every second.

Shortly after sunrise, when the city was officially still a pleasant 63 degrees, they made their first rounds. They repeated their trips at 3 p.m., while the temperature soared past 91, and again at 7 p.m., when the day had still refused to cool below 91.

Those were only the official measures of the day’s heat. Actual temperatures that people experience vary from town-to-town and even neighborhood-to-neighborhood.

The drivers aimed to map real hot spots -- places where vulnerable people may feel the brunt of heat the most as the world’s climate heads into new territory.

“The disparities that can cause temperature differences between city blocks can vary as much as 20 degrees,” Jamie Stroble with King County’s Department of Natural Resources and Parks said.

Sponsored

Areas dominated by pavement and other hard surfaces absorb and retain heat more than leafier locations.

Similar car-based studies in Tacoma and other cities have found that "redlined" neighborhoods—areas that mortgage lenders in decades past deemed too risky for loans because people of color lived there—are usually hotter in the summer than wealthier neighborhoods.

“Across 108 cities, those areas were 5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than their counterpart areas,” said Portland State University urban planning professor Vivek Shandas.

“There is a very clear environmental justice dimension. This is a systematic pattern,” he said.

Seattle and King County hired Shandas’s consulting firm, CAPA Strategies, to help map the county’s urban heat islands.

Sponsored

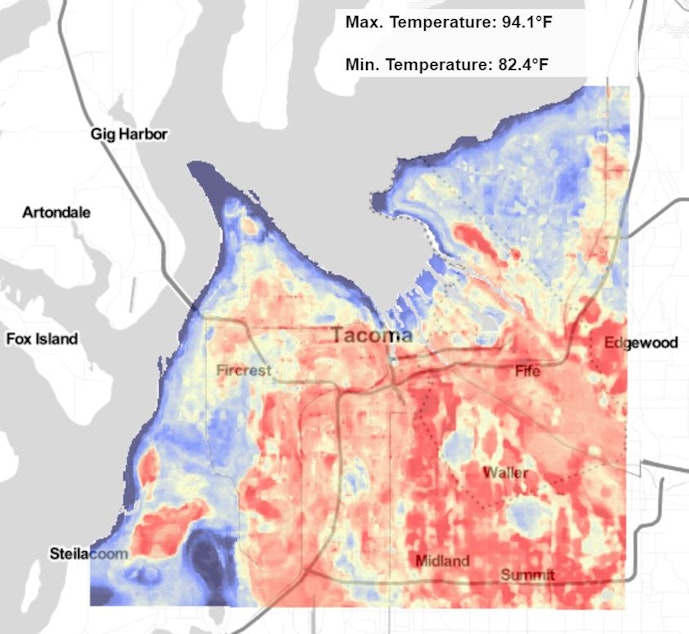

The firm mapped Tacoma’s hot spots last summer. When waterfront areas reached 82 degrees in mid-afternoon, other parts of town hit 94.

Of course, summers in the Puget Sound region are quite cool compared to most of the country.

As a result, we don’t have a lot of air conditioning here.

“We’re just not ready for those hotter temperatures,” Lara Whitely Binder with King County’s Department of Natural Resources and Parks said.

Sponsored

University of Washington researchers say the hottest days already lead to more 911 calls, hospitalizations and deaths here. Their 2016 study found the risk of death rose 10% on Seattle’s hottest summer days.

Those health impacts are expected to worsen as the climate keeps heating up, globally and locally.

Efforts to cool the hottest neighborhoods, by adding shade trees and light-colored roofs that reflect heat back to the sky, might help turn that trend around.

County officials say the mapping will help them direct trees, green spaces, spray parks, cooling centers and energy-efficiency retrofits to the neighborhoods where they are most needed.

Doing so could both protect vulnerable populations and help reduce strain on the region’s electrical grid from expanded use of energy-intensive air conditioners.

Sponsored

Shandas said many of the redlined areas that tend to heat up the most sit next to large industrial parks, highways and big-box stores.

“When one group said, ‘not in my back yard,’ another group said that in not-as-loud as a voice, and they ended up receiving those developments,” he said.

All those developments can act as heat magnets.

“The concrete and the asphalt laid down in those areas was really driving what was happening in the adjacent areas,” he said.

While newly planted trees might take a decade or more to provide much shade, measures like replacing dark roofs with light roofs can provide immediate relief from the heat.

Sponsored

Those measures would do little to address the global emissions of greenhouse gases that are heating the planet.

But most climate watchers now agree that learning to adapt to a hotter world is every bit as necessary as transitioning away from the fossil fuels that are destabilizing our world.

Correction, 12:45 p.m., 8/7/20: An earlier version misspelled Jamie Stroble's name.