The deadliest heat wave: Lessons from the NW's extreme heat

Washington state experienced the deadliest weather disaster in its history in June 2021. At least 125 people died in Washington and 115 in Oregon. Many were found alone in their apartments, trailers, and cars.

According to Weather Underground historian Christopher Burt, never in 150 years of record keeping had temperature records anywhere on Earth been smashed so hard as they were by the Pacific Northwest’s June 2021 heat wave.

In Washington, 2,000 people crowded emergency rooms after suffering heat strokes or other harm from prolonged, record-breaking temperatures.

RELATED:

- To prevent deaths during Washington's next heat wave, we need a heat action plan

- NW heat wave sparks skepticism of new Conservative Climate Caucus

- Heat wave lesson: Hydration is key, especially for older people

- WA issues new protections for outdoor workers following extreme heat wave

One month after the heat dome descended on the region, KUOW looks back at the human toll of extreme heat and what officials say they learned from the unprecedented emergency.

Sponsored

Jeffrey Rochlin, 41, was found dead, overheated, in his apartment in Auburn.

Debra Moore, 68, of Bonney Lake fell on a sidewalk in Enumclaw after getting out of her car. With the neighborhood’s window blinds drawn for insulation, according to Enumclaw police, nobody noticed her lying there for about two hours in 106-degree heat.

Barnett Moss, 63, was found dead on the porch of the church in Olympia where he had spent most nights for the past five years.

While many people died alone and unnoticed, the astounding temperatures also captured global attention.

Sponsored

“What’s going on in the Northwest USA and western Canada is simply breathtaking,” the BBC reported. “Warmer than Abu Dhabi and Kuwait.”

In Washington, roads buckled. Crops shriveled. Forests turned to tinderboxes. Shellfish cooked and died by the millions on Puget Sound.

Emergency managers in cities including Chicago, Philadelphia, and Phoenix have heat action plans. In the Pacific Northwest, they prefer all-purpose emergency plans for various hazards.

“Urban heat response plans are currently limited or otherwise do not exist for most communities, even large ones,” Portland State University urban planning professor Vivek Shandas, who has advised the cities of Seattle and Tacoma on protecting vulnerable neighborhoods from extreme heat, said in an email.

As the heat dome approached, governments and hospitals scrambled to respond. Even in a climate already made a few degrees warmer by fossil fuel pollution, nobody expected it to get so hot so fast.

Sponsored

“We deal with extreme weather, but the notion of having a multiple-day, 100-plus degree temperature incident was so unlikely,” said Pierce County emergency management director Jody Ferguson.

In January, King County had applied for a Federal Emergency Management Agency grant, still pending, to develop a heat action plan.

“We knew we needed to plan for more heat events,” Lara Whitely Binder, the county’s climate preparedness program manager, said in an email. “Who knew we would get such a powerful reminder so quickly!”

Some hospitals in King and Snohomish counties had to cancel elective procedures to handle an unexpected deluge of critically ill patients with heat strokes.

“We even got to the point where we almost ran out of ice, which is one of the mainstays of treatment to cool patients down, so it definitely put some stress on the system,” said emergency physician Bryce Snow at Providence Regional Medical Center in Everett.

Sponsored

Emergency planners say they did everything they could to keep people safe, given limited resources and pandemic-safety restrictions.

“You know, I can't give a bottle of water to every resident of Pierce County,” Ferguson said.

Governments opened up spray parks, wading pools, and cooling centers to help people escape the heat. Some efforts worked better than others.

Seattle officials say a national chlorine shortage forced them to reduce the operating hours of city wading pools.

Sponsored

Seattle Parks and Recreation crews worked overtime to reopen drinking fountains shut off during the pandemic. But by Saturday, June 26, the first day of triple-digit heat, 40% of fountains were still not running. By the end of June 28, the third and hottest day, all but 13% were running.

In Seattle, the vast majority of community centers don’t have air conditioning.

Seattle Parks and Recreation managed to turn four of them into cooling centers, though only two were open on Monday, the hottest day. The Rainier Beach and Northgate centers had to resume their weekday service as day-care centers. The four community cooling centers helped 107 people dodge the heat.

In Pierce County, just 63 people visited the 21 cooling centers on the hottest day – about three people per cooling center – despite outreach efforts and free bus rides.

“I think Covid and the pandemic did play a part in this because the idea of going into a congregate cooling center, that's very scary,” Ferguson said.

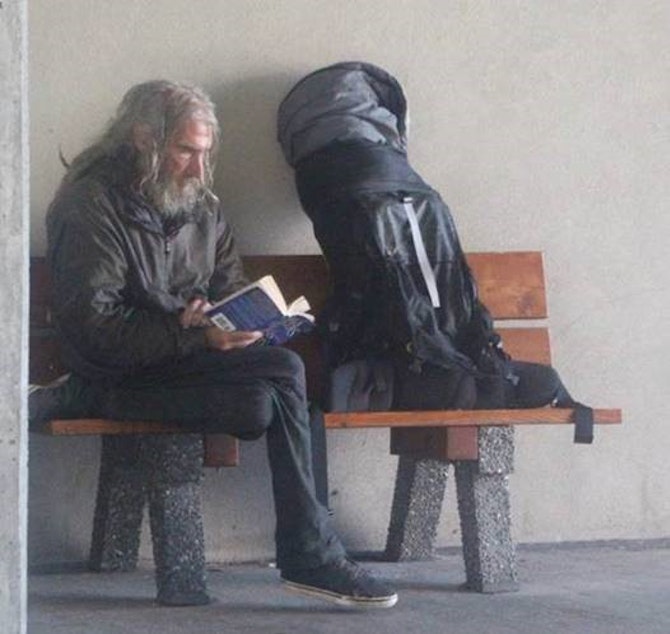

If you’re homeless, going to a cooling center can also mean abandoning your possessions.

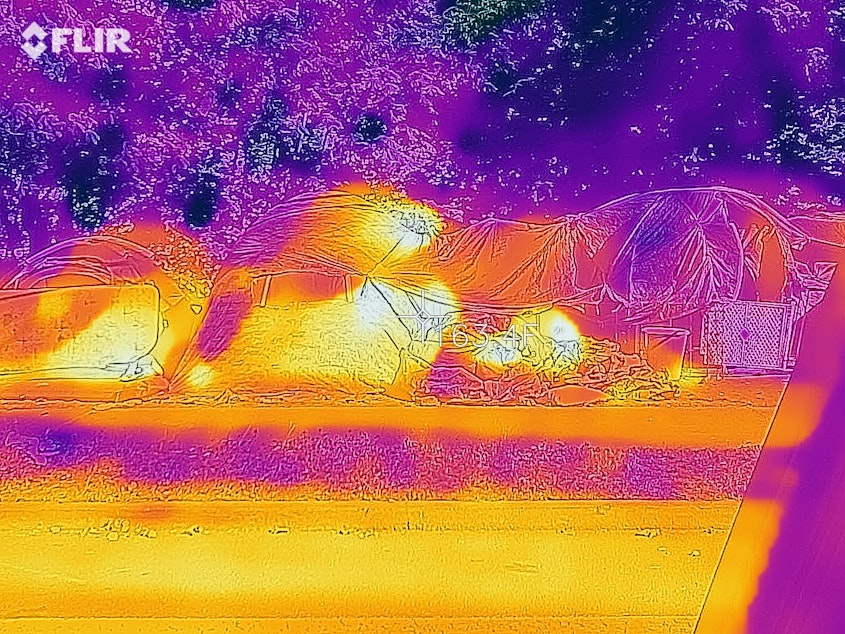

In Portland, Shandas documented surface temperatures of 163 degrees on tents in a homeless camp on June 28 and pavement temperatures as high as 195 degrees: hot enough to cause third-degree burns.

“Surprisingly, the people living in tents were not going to the Convention Center, which was a government-sponsored cooling center, and located just two blocks away,” he said.

Mayor Victoria Woodards says Tacoma had better results at delivering water and medical supplies to homeless camps. Niagara Bottling in Puyallup donated 24,000 bottles of water.

“Thanks to all of our local homeless advocates, who really did the bulk of the work, we were able to get water out to all of our homeless encampments,” Woodards said.

Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan declined to be interviewed. But Seattle officials say their outreach teams contacted more than 2,000 vulnerable people.

“The city did a remarkable job, given that they didn't have a heatwave early warning and response system or a heat action plan,” University of Washington climate and health researcher Kristie Ebi said.

“There's lots of logistics involved in this,” Ebi said. “You can open up cooling centers -- how do people get there? Do you want people who are in high risk to walk to the bus station and wait for a bus to go to the cooling center? Are the cooling centers in the neighborhoods that are most at risk? How long are the cooling centers open? If we've got really hot nights, are you staying open all night?”

Washington Gov. Jay Inslee says there’s only so much government or anyone can do to make heat less deadly.

“When you have this kind of heat, you're going to have people in this fatal situation,” Inslee said. “Because some folks may not recognize the problem. Some folks may not be cognizant of their surroundings. That's why we have to stop this heat at its source.”

Climate scientists say heat waves will become more common as fossil fuel pollution keeps altering our climate. Heat waves as truly extreme as this one remain unlikely — though they could come as frequently as every 5 to 10 years over the coming decades if the world does not drastically reduce greenhouse gas pollution.

So what happens the next time the Northwest turns into an oven?

“We'll be better prepared,” King County emergency management director Brendan McCluskey said. “There is a planning process going on now that encompasses not only heat events, but also smoke events.”

Emergency officials are doing what they call “after-action reviews” to figure out what worked and what didn’t. McCluskey and others say they are already making improvements instead of waiting for those reviews to be complete.

Seattle officials met with Ebi, whose recommendations include tiered warnings to alert the most vulnerable first, in July and say they are looking at ways to expand cooling center options and incorporate some of Ebi’s ideas.

Planners are working on adopting specific temperature thresholds as triggers for different responses and improving cooling options and outreach to the most vulnerable, including older people living alone.

“These changes will require significant investment, but we can't ignore our new reality,” Seattle emergency management spokesperson Kate Hutton said in an email.

Pierce County’s Jody Ferguson says emergency planners sometimes get criticized for focusing on worst-case scenarios.

“Now we've had what seems like a couple of years so full of unprecedented, unimaginable events that I don't think we're going to get that criticism anymore,” she said.