I put people on mechanical ventilators. Here's what I've seen

Voices of the Pandemic features people in the Seattle area on the front lines of the coronavirus outbreak.

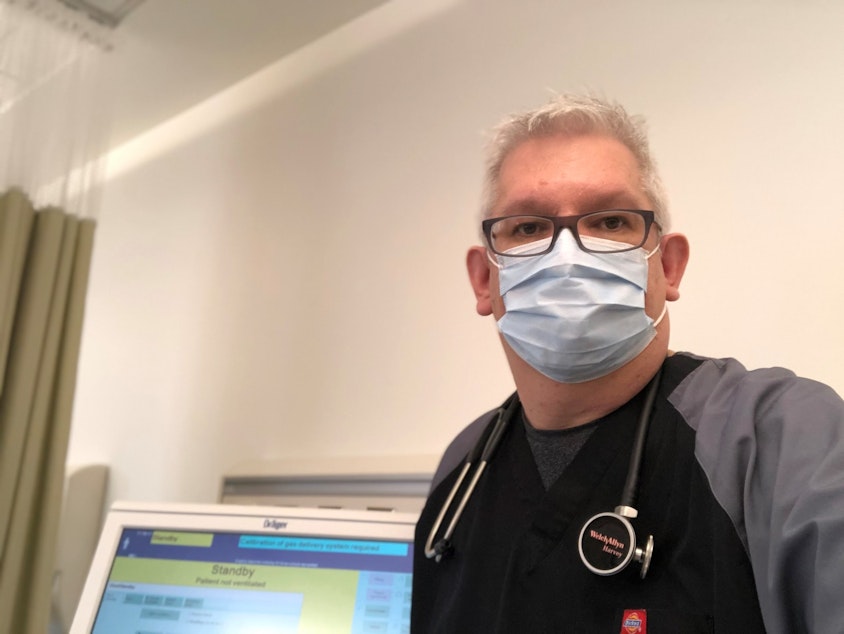

Scott Mahoney is a respiratory therapist, in a Seattle area hospital. Part of his job is to put people on ventilators. He also teaches clinical education at Seattle Central College, and is a director of the Respiratory Care program there.

He said before Covid-19, most people who were ready to go on a ventilator were visibly gasping for air, unable to concentrate on anything but breathing. They can barely stand and are "obtunded," or difficult to arouse.

But a lot of COVID-19 patients look very calm and alert.

In his own words, Mahoney tells us about a time he went to intubate someone, and entered the room to find the patient texting family members, almost as if nothing was wrong.

T

hat’s not a normal thing. And the fact that the patient was awake and alert enough to be sending messages to their loved ones was, to be perfectly honest, very shocking.

Because, and I haven’t said this yet, one of the things that’s really scary about Covid patients who end up on mechanical ventilation is a large percentage of them do not survive that event. The vast majority of patients do not live, when they get to that point.

So what’s poignant to me as a clinician is witnessing these last conscious moments of these patients who are alone in the hospital with no family around them, sort of communicating these last wishes and or well wishes to their loved ones, prior to undergoing intubation, sedation, mechanical ventilation, and a very high likelihood that they will not live beyond that.

And it’s heartwrenching.

Sponsored

O

ne of the things that's difficult is when we come to the decision that we can no longer provide enough support for that patient and or the patient's illness has grown to the point where no amount of support that we can give is going to make a positive difference.

What I'm getting at is that there are many times in these situations where we're having to make decisions, along with the family, obviously, about the withdrawal of life support.

And when we get to that point when we make that decision, when we take them off the mechanical ventilator, that patient again is by themselves, and they're going to take their final breaths in an ICU bed with the door closed, with people standing by them they do not know who are wearing protective gear. And that is how they're going to exit this world.

It's also a privilege to be there for those patients and to be with them in that moment.

Sponsored

But it is very difficult as a caregiver.

S

o the patient I spoke about ... survived. It was an incredibly long process. Greater than two weeks. They ended up having to have a slightly different airway put in. But the patient eventually did end up coming off the mechanical ventilator completely. It was a huge relief to find out later on, that they did in fact, survive their battle with Covid-19.

Reporter's note: An early study showing the vast majority of patients in a New York group of hospitals did not survive intubation has raised alarm. But as a growing number of patients on mechanical ventilation provide more data to scientists, a follow up study, still under peer review, could show the mortality rate decrease significantly. Furthermore, Mahoney notes that data regarding patients' needs while on the ventilator is increasing too, which is continually improving mechanical ventilation strategies and hopefully, outcomes.

If you have a story about a moment when you faced something new, during the pandemic, we'd like to hear from you.

Alec Cowan composed music for this story.