Heat wave likely killed far more people in Washington state than reported

Hundreds more people died in Washington state during the last heat wave than previously reported, new analysis reveals.

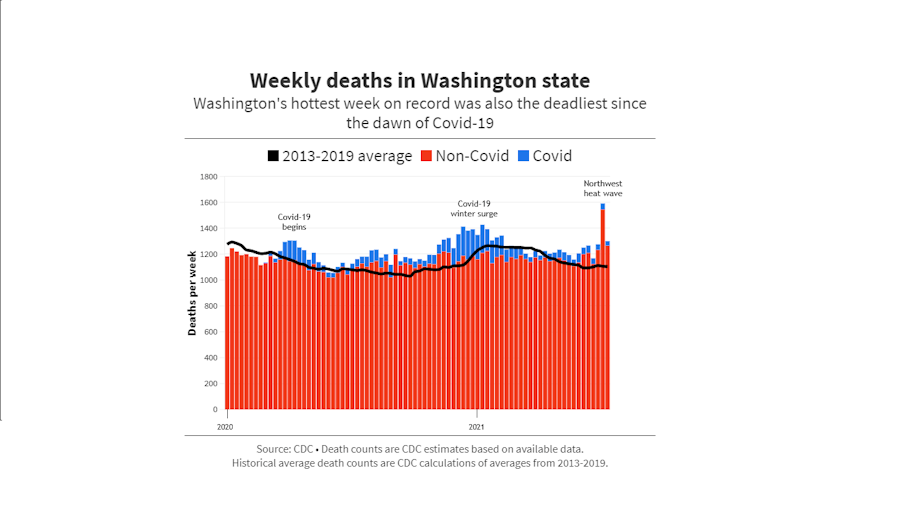

More than 400 people likely died during a single week of the heat wave in Washington state last month. That’s according to new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

After the heat wave, the state health department reported that 129 people died from the heat, but the death toll from the heat may have been far higher during what was the deadliest week in at least four years.

The set of numbers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows there were around 485 so-called “excess deaths” during one week of the heat wave.

Excess deaths compare the estimated death count in the state that week to average counts from the years 2013-2019. About 46 of those “excess deaths” were attributable to Covid-19, CDC’s estimations show.

The New York Times first reported on the CDC “excess death” data for Washington and Oregon.

Sponsored

The CDC’s excess deaths data factors in deaths that may not be attributed directly to heat, like heat stroke or hyperthermia, but could be related.

“It wraps all possible causes of death into one number, and it's a little bit more inclusive and less precise,” said Howard Frumkin, an epidemiologist at the University of Washington. “On the other hand, if you just look at the death certificates that say ‘heat,’ you're going to miss some of the heat-related causes.”

The exact role heat may have played in the one-week spike in deaths remains unclear. It’s possible, though Frumkin says unlikely, that various other factors could have made that week especially deadly.

“There's nothing else that's likely,” Frumkin said. “I think what we're seeing is the impact of extreme heat.”

Official counts of heat-related deaths do not include those related to poor air quality, which is worsened by hot, stagnant air, or some causes that may be related to heat-induced stress, like homicide.

Sponsored

“We do have pretty good evidence that aggressive behavior and violence increase in very hot weather,” Frumkin said.

Official tallies of heat deaths also exclude accidents involving drowning or activities linked to extreme heat.

“Someone’s boating death is a great example,” said Steve Mooney, an epidemiologist at the University of Washington. “It’s not directly attributable to heat in the sense of heat stroke, but it arguably is attributable to heat in the sense that had it not been hot, they would not have gone out.”

Jefferson Ketchel, executive director at the Washington State Public Health Association, said that understanding the impact of heat could be improved by more complete, accurate, and speedy collection of public health data. “Public health will be better able to do its job if it had access to real time data as to what’s going on in their communities,” he said.

Still, “no matter how this data gets interpreted, we are going to see more illness and more deaths because of heat, because of climate change,” Ketchel said. “That has a real impact on all Washingtonians.”

Sponsored

While all feel the heat, it hits some harder than others. Along with its official count of heat-related deaths, the state posts a list of people who are at higher risk – including elderly or overweight people, and children under four.

According to the Washington’s Department of Health, most of the heat victims were at least 65 years old. Men were more likely to die than women. Six Native Americans died – a number out of proportion to their share of the population.

Nonwhite people across various races, and impoverished people, are also more vulnerable throughout the United States, according to a peer-reviewed study published in Earth’s Future last month.

“As with all things health related, privilege is protective,” said Mooney. “The consequences fall most strongly on the least privileged, sadly, as always.”

All of this will get worse as the climate continues to change, and there aren’t “easy fixes,” Mooney said.

Sponsored

“The heat framing in the Northwest is that we are one of the least air conditioned places in the country,” Mooney said. “But outfitting everyone with air conditioners would have a whole lot of other climate-related issues that could be bad in its own right.”

Frumkin said it was key for governments to identify the people most vulnerable to heat in advance and make sure plans are in place to care for them when the heat sets in. “We need to be moving in that direction,” he said.

More heat is due in the Northwest. Today, the National Weather Service issued an excessive heat warning for parts of Washington, which will remain in effect until 8 p.m. Saturday.

Gracie Todd is a Roy Howard Investigative Fellow at KUOW.