Have you heard about Temperance and Good Citizenship Day?

Temperance and Good Citizenship Day falls under the #FutureVoter program out of Washington's Secretary of State’s office. But it has not always been wrapped up in the state's voter registration efforts.

Every January, eligible students in Washington state public schools are given an opportunity to register to vote. School’s must offer the opportunity when they can — it’s the law.

When Temperance and Good Citizenship Day was first established in 1923, the Temperance Movement — the social movement against drinking alcohol — was in full swing. And it was strong in Washington state.

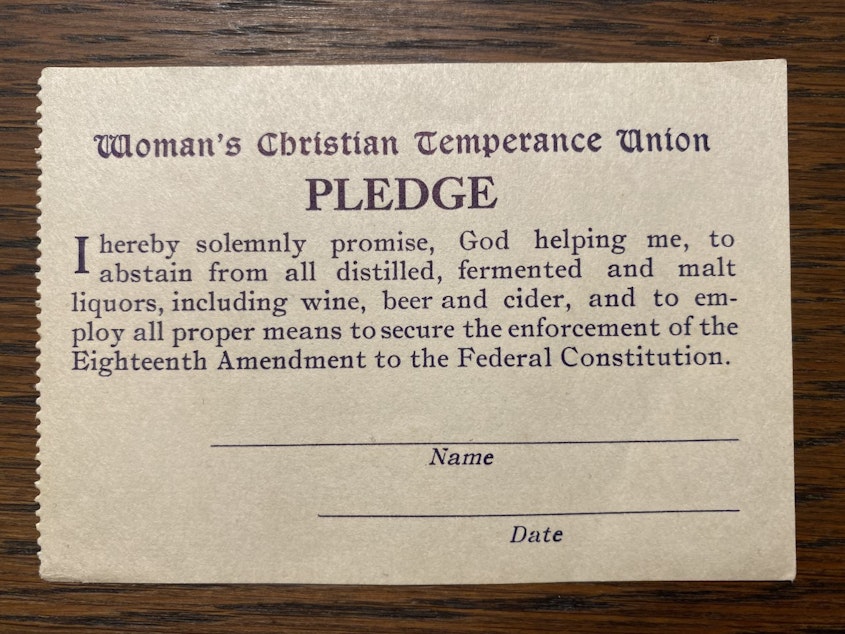

Church leaders, like reverend Mark Matthews in Seattle, alongside groups such as Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and the Anti-Saloon League were able to spread influence and push for change across the state with ease.

Washington state went “dry” in 1916, four years before the nationwide prohibition of alcohol sales, production, and import.

Sponsored

With new laws came outreach and cultural shifts, including prevention measures among young people.

Brad Holden, a local historian and author of Seattle Prohibition: Bootleggers, Rum Runners and Graft in the Queen City says that spreading temperance — abstention from alcohol — to kids primarily took place in churches.

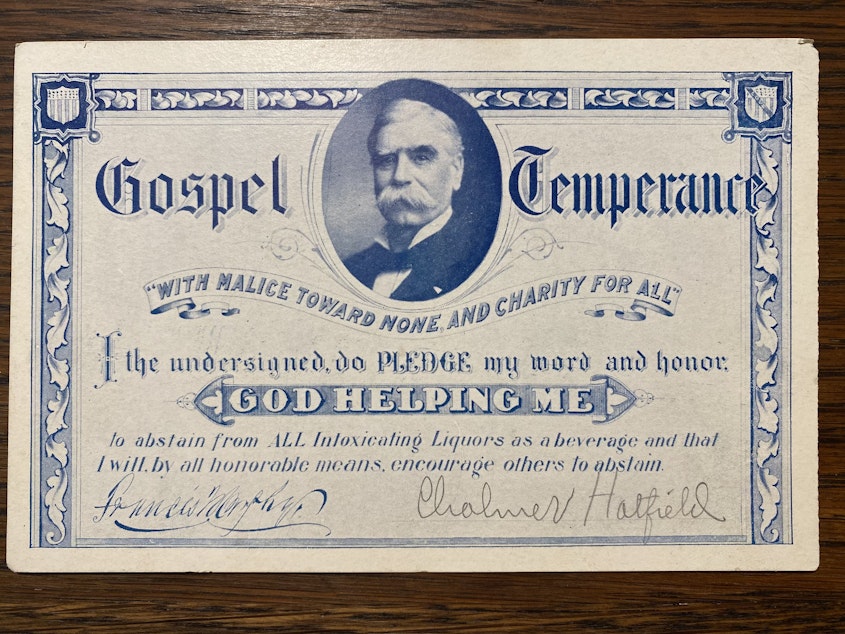

“During the '20s they would have kids sign these abstinence cards,” Holden said. “Basically pledging I – and you’d write your name — promise to abstain from drinking alcohol.”

The holiday changes

But in 1969, the holiday evolved. Washington state amended the holiday away from booze to rights and responsibilities of U.S. citizens — being a good citizen. However, the initial name stuck.

Some teachers choose to teach the ideas of temperance as self-restraint, peaceful or non-violent protest in place of abstention from alcohol.

“We have a lot of conversations about that and whether that name helps or hurts our cause,” says Jerry Price, OSPI’s Associate Director of Content for social studies.

OSPI is the Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction.

The holiday goes beyond voter registration and is part of a whole approach to civic education in social studies classrooms across the state.

At its core, Price says, “it’s about empowerment and student voice.”

Sponsored

“A healthy democracy demands that we have people who understand how the system works and are able to engage with the system in ways that are positive.”

Joshua Parker and instructional specialist for social studies in North Thurston County says approaching civic education on Temperance and Good Citizenship Day in the classroom does come with challenges.

“As teachers we want our students to be empowered and informed to make a difference and be a positive force in our society. But we don’t want to leave them jaded,” he says.

Parker says that learning the structures of government or structures in our society can disrupt a student’s idea of fairness.

“Even that term 'citizen' may or may not apply to all our students,” he says.

Sponsored

Parker says that students may be undocumented, unhoused or without an official address, and that some may have felony convictions before turning 18 years old. All of these pose significant challenges to how they engage in the community.

“We want kids to use their civil rights and do their civic responsibilities, but we also don't want to give those opportunities in ways that are outing kids,” Parker says.

The approach to civic education varies from classroom to classroom, however the state’s learning standards aspire to have students to come away with the skill to interpret historical events, source information, and critique it.

“I want kids to be thoughtful skeptics,” Parker explained. “That idea of being critical thinkers — which is such an important part of the social studies classroom — is becoming more and more challenging in face of all of the information that is put in front of us.”

Listen to the full conversation on this topic by clicking the audio above.