Gov. Inslee brings apples to Washington town decimated by wildfire, leaving bitter taste in residents’ mouths

Bridgeport, Washington, is an apple town. Orchards abound, and many who live in this tight-knit community farm, pick, or sort fruit at packing plants.

So it was surprising to the people of this agricultural community, when, on the Saturday after their town all but burned down, Gov. Jay Inslee arrived with an offering of apples.

“A lot of people felt that as a slap in the face,” said Shannon Hampe, a wildfire relief organizer. “Him nor his office are in touch with what happens over here and who we are.”

For the people of Bridgeport, many of whom had spent smoky nights huddled in tents and on neighbors' couches, and whose drinking water is unsafe, the apples signaled a disconnect between them and the halls of state power, 250 miles to the west in Olympia. A misguided symbol of Washington solidarity, delivered by politicians booked on the next bus out of town.

“People are very, very upset,” said Mario Martinez, who has lived in Bridgeport for 45 years. Martinez said Inslee’s visit was the talk of the town. Neighbors were outraged that Inslee would illegally bring fruit to Bridgeport from an area under apple maggot quarantine. His donation was upsetting to others who said they needed supplies, not more apples.

“Some people are living in tents; some people with relatives,” Martinez said. “The most challenging thing is building back, you know. There’s people asking for money, which a lot of people don’t have it here.”

Update: Dangerous maggot larvae found in apples that Gov. Jay Inslee gifted to wildfire-ravaged town

The Pearl Hill Fire burned down an estimated 20 homes in the area – significant for a town that spans slightly more than one square mile and has a population of roughly 2,600.

The Douglas County Public Utility District is still working to restore power, and cell service is spotty, depending on the carrier. Municipal water has been turned back on, but isn’t safe to drink yet, Martinez said.

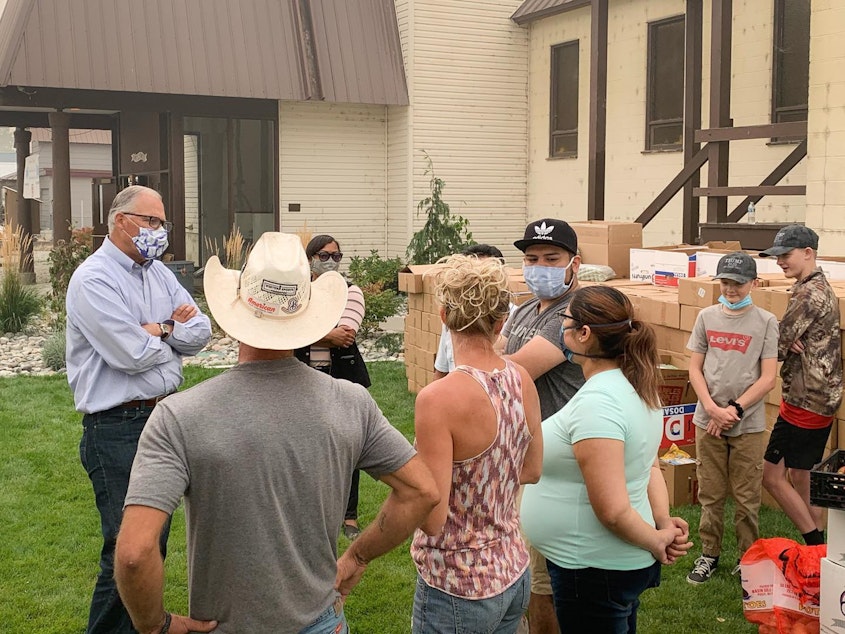

Hampe estimated that Inslee arrived at the Foursquare Church in Bridgeport shortly after 11 a.m. With him was a small entourage of staff, and a plastic flat of red apples Inslee personally picked from his orchard, Hampe recalled Inslee said.

Inslee, who has worn apple pins, has expressed fondness for apples. In Selah, where he raised his family, he lived on four acres of hayfields surrounded by apple orchards.

Hampe lives in Pateros, 20 minutes west of Bridgeport.

Douglas County as a whole has voted primarily Republican, supporting Donald Trump in 2016, presidential candidate Mitt Romney in 2012, and voting against Inslee during his last reelection bid.

But Bridgeport is a purple dot in this deep red county, and voters in the town were roughly split between casting votes for Inslee and Bill Bryant in 2016, according to the Douglas County Auditor website.

Most of the town’s residents are Latino, some of them Spanish speakers who rely on others to help translate. For those already living in the economically struggling area, losing your home means losing everything.

Hampe has witnessed the kind of devastation that wildfires cause, and the level of response needed to recover – especially in small, rural towns miles away from cities, or large stores where clothing, blankets, and other necessities can be purchased. The nearest two box stores to Bridgeport are Walmarts. Both are 40 minute drives either north or south, through landscapes similarly devastated by wildfires.

Hampe said providing assistance to people has been trickier this year. The language barrier for some meant they needed to find translators. It was even harder to reach undocumented people, who traveled to Bridgeport for seasonal work, and who were wary of being deported.

"Key people in the Latino community have reached out and said, ‘It’s okay; trust them,’ so slowly people are coming in to talk to us, but we’re not the government,” Hampe said.

A government response takes time, more time than the tiny town of Bridgeport had to render aid, she said. So she and her neighbors jumped into action, taking the initial emergency response into their own hands.

On the Saturday that Inslee visited, Sept.12, Hampe estimated they fed more than 750 people with donations, representing some 180 families, and distributed more than 20 pallets of water. The National Guard arrived two days before, on Thursday.

Before Inslee left, Hampe showed him the church basement, where the donations from around the area, and the state, were stored.

“I wanted him to see what community could do right now for people in need,” she said.

Inslee’s staff signaled that it was time for him to leave, after a ten-minute visit at the church, but not before staff snagged a photo of Inslee for his social media. It was posted four and a half hours later.

The governor's office declined to comment for this story.

Hampe’s 14-year-old son, Dane, ate one of the governor’s apples, and said it tasted good. Another apple, that Hampe cut open, was rotten.

It’s hard to say what became of the rest.