Extreme heat wave cooked acres of shellfish, spared others, study finds

An estimated 1,100 people died in the extreme heat of June 2021 in British Columbia, Oregon, and Washington.

So did millions of sea creatures.

While the record-smashing heat killed shellfish across areas spanning hundreds of miles, a new study finds that animals on some beaches escaped with much less damage than others.

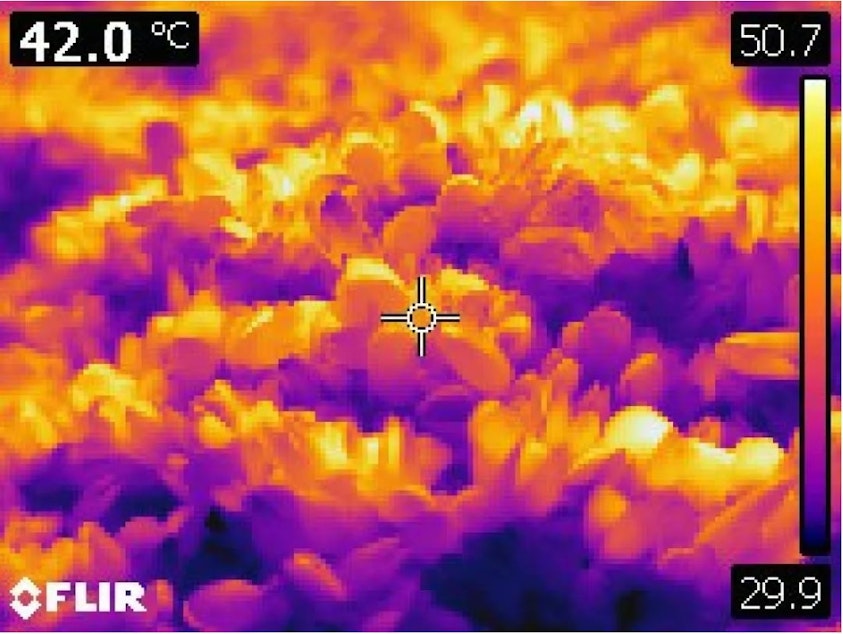

Along Puget Sound, the withering heat coincided with extremely low afternoon tides. The unfortunate combination exposed clams, oysters, mussels, sea snails, and barnacles to triple-digit temperatures for hours at a time.

“They were cooking in their own shells,” said study coauthor Julie Barber, a shellfish biologist for the Swinomish Tribe.

Species like acorn barnacles, which tend to live at the upper end of beaches and spent much more of the heat wave out of the water, were harder hit than clams and oysters just a few feet lower.

Fewer shellfish died on beaches that faced north or had overhanging vegetation or cool water seeping up from underground, according to the new study in the journal Ecology.

Sponsored

On Washington’s outer coast, the low tide came in the morning, about four hours before Puget Sound, and the extreme afternoon heat took a less extreme toll.

Biologists recorded their observations of 24 species at 108 sites on the outer and inner coasts of Washington and British Columbia.

Very few locales' shellfish populations had been quantified before the heat dome, making before-and-after comparisons difficult. Instead, researchers recorded their overall impressions of places they knew well, often from years of repeated observations.

They devised a simple, impressionistic scale to quickly assess shellfish populations in the immediate aftermath of the heat dome.

They ranked the shellfish populations on beaches they had observed for years from 1 (much worse than normal) to 5 (much better than normal).

Sponsored

Biologist and shellfish farmer Joth Davis, who was not involved in the study, said it was a good effort to describe the impact of the heat dome on the region’s shellfish in general terms.

“The data presented is very thin and really only post-fact descriptive,” Davis said in an email. “But that’s all there is to work with given that the event came out of the blue, so to speak.”

Barber said just because an observation doesn’t produce hard numbers doesn’t mean it isn’t valuable, especially if it arises from deep experience with a particular place, something she and her 10 coauthors have.

“These are people that have been spending, you know, in my particular case, over 12 years on these beaches, and so we know very well when something really wrong has happened,” Barber said.

Sponsored

Barber said she realized the heat would take a terrible toll on the creatures she has dedicated her life to studying after she saw a shallow tidepool turn into essentially a pot of hot water.

“All the butter clams in that one section had unburied themselves and were basically frying in the sun,” she said. “It's not an easy thing to see. I love clams so much.”

Barber said the idea for a big collaboration looking at regionwide impacts hit her there on the sweltering beach.

“We just looked around and saw an awful lot of animals dying or extremely stressed out, and a little light bulb went off in my head," she said. "I thought, ‘Oh my God, I need to contact my colleagues and find out what they're seeing, and we need to start talking with one another.’”

Sponsored

Shellfish are a key part of many tribal cultures and diets.

“There were fairly high mortality rates on some beaches that we harvest from regularly and some of the larger beaches that we depend upon a lot,” said Joseph Pavel, a Skokomish tribal member and the tribe’s director of natural resources.

While shellfish farmers might be able to adjust their practices to adapt to extreme heat—Davis’s shellfish farm even covered oyster beds with bedsheets to provide shade—that’s not really an option for shellfish in the wild.

“Umbrellas have been suggested,” Pavel said, then laughed. “That’s a lot of umbrellas.”

Sponsored

Pavel says tackling the pollution that’s causing global climate change is the key to saving shellfish and the cultures that rely on them.

“It's a global phenomenon, and it has to be dealt with globally,” Pavel said.

The previously unthinkable temperatures of the Northwest heat dome would be "virtually impossible" without human-caused climate change, according to scientists with the World Weather Attribution collaborative. Their study making that claim is still under peer review for publication in the journal Earth System Dynamics.

The Ecology paper only looked at Northwest shellfish in the wild and did not address impacts to shellfish farms.

At least 60 Washington shellfish producers applied for disaster assistance from the U.S. Department of Agriculture following the heat wave.

Agriculture officials did not respond to requests for information on the status of that disaster aid.