Extreme heat cooks shellfish alive on Puget Sound beaches

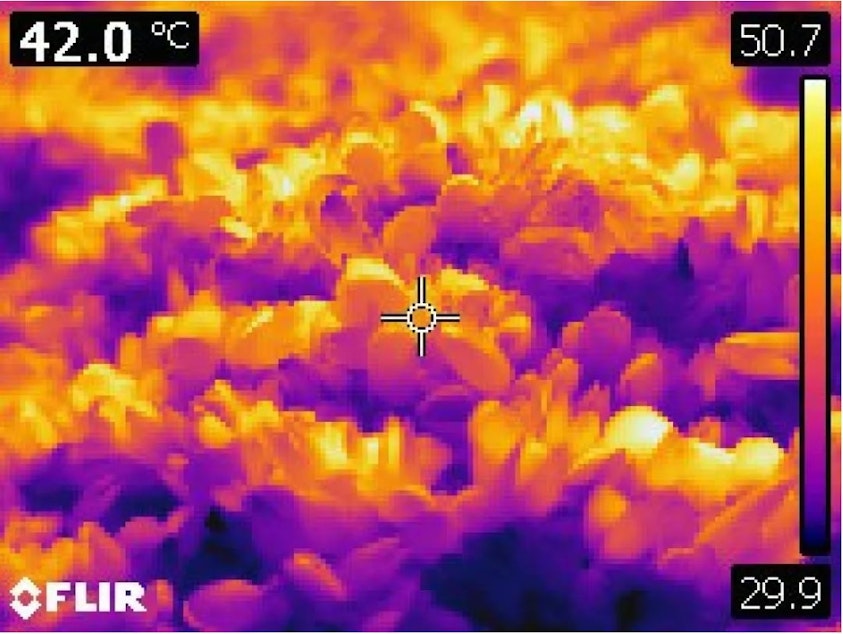

A record-shattering heat wave June 26-28 coincided with some of the year's lowest tides on Puget Sound. The combination was lethal for millions of mussels, clams, oysters, sand dollars, barnacles, sea stars, moon snails, and other tideland creatures exposed to three afternoons of intense heat.

A shellfish farmer on Little Skookum Inlet in south Puget Sound reported the muddy sand on his beach reaching 135 degrees.

“It was a Murphy’s Law of extreme heat and the lowest tides of the year at the same time,” said Megan Dethier, the University of Washington Friday Harbor Laboratories director.

“This was so far above normal,” she said. “The fact that it’s killing mussels, which are some of the toughest creatures around, is really striking.”

“It wasn’t good,” said Chris Burns, a natural resources technician with the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, of the scene when he walked onto one of the tribe's beaches on Sequim Bay. “The first thing I saw was vultures on the beach — which I've never seen vultures on the beach — so I pretty much knew what was going on.”

Sponsored

What was going on: The scavengers were feasting on a uniquely 21st-century buffet of climate-baked shellfish.

Burns said it smelled like a clambake.

Observers at other beaches had less flattering descriptions: "awful," "so bad," and "a very strong smell of rotting animals."

The Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe has been using its beaches to restore populations of Olympia oysters, a native species.

Sponsored

“They're really temperature sensitive,” Burns said.

He estimates that the heat was too much for about half of the Olympia oysters the tribe has been working to restore.

“About half of them had opened up,” Burns said. “They were dead, basically.”

Dying shellfish lose the ability to "clam up." They open wide, showing their fleshy insides.

“They're usually shut,” Swinomish Tribe biologist Julie Barber said of cockles, a traditional food of many Washington tribes.

Sponsored

On a beach on Fidalgo Bay near Anacortes, “the cockles were open and gaping, and most of the ones that I saw were dead,” she said.

Chris Harley, a biologist with the University of British Columbia, estimated that hundreds of millions of mussels, if not more, died in the three-day heat wave in Washington and British Columbia.

“The total number of animals that died is probably well over a billion,” he said.

“It's such a large number of species over such a large area that it's just a staggering amount of death,” Harley said.

Sponsored

Creatures of Washington and British Columbia’s intertidal zones, which are covered by cool sea water when the tide is in and exposed to the air twice daily as the tide goes out, have evolved to handle a wide range of temperatures and conditions.

But all creatures have their limits.

“Barnacles very high on the shore can survive temperatures above 100 degrees Fahrenheit,” Harley said. “But the rocks got up to 120 degrees Fahrenheit, which is far too hot for even those really, really tough animals to live through.”

Sponsored

“We saw the moon snails crawl out of their shells to get away from the heat,” biologist Teri King with Washington Sea Grant said. “We saw shore crabs die.”

Some mobile animals like crabs and sea stars may have been able to flee with the tide and stay underwater, and some deeper-residing clams like geoducks may have been able to burrow far enough into the mud to avoid lethal temperatures.

Shellfish farmers who saw the forecast for unheard-of heat could try to reduce their losses.

“We tried to get everything out that we could beforehand,” said Justin Stang with the Hama Hama Oyster Company on Hood Canal. “We told everyone, ‘Let’s get shellfish out to the restaurants before the big heatwave hits.'”

Stang said all species and age classes of the company's oysters and clams suffered some losses, though he did not expect total devastation.

To qualify for U.S. Department of Agriculture disaster assistance, shellfish farmers need to document how many of their diminutive livestock were killed by the heat.

“Unfortunately, the story is going to take time to know what really happened,” King said.

She said some areas were hit harder than others and that impacts on some organisms might not be immediately obvious.

“It wasn't an instantaneous kill for some species,” King said. “They are struggling, struggling, struggling, and then they finally give up the ghost. So it's kind of delayed.”

“We don’t know what the magnitude of it was at this time,” Skokomish Tribe natural resources director Joseph Pavel said. “Really, without a before and after, it’s hard to ascertain what the true impact may or may not have been.”

Another series of extra-low tides with this weekend’s new moon should let biologists and shellfish farmers get a better sense of the damage.

Scientists say surviving marine life from waters just below the intertidal zone could repopulate devastated tidelands. But that process can take years for some species.

“The balance is going to be how long is recovery versus how long until the next severe heat wave,” Chris Harley, the UBC biologist, said. “And if the heat waves start happening more rapidly than the recovery time, that's when you will start seeing really big changes in what the shoreline ecosystems look like that are more permanent.”

“These heat waves are going to occur more and more often, and that is because of climate change. So we need to really kind of focus on the root of the problem,” Swinomish biologist Julie Barber said.

Heat waves and other weather extremes around the world are being worsened by a climate increasingly altered by fossil fuel pollution.

“What to do???” the Hama Hama Oyster Company asked on Instagram. “Please vote for politicians who are brave enough to address climate change.”

Beyond the immediate dieoffs, Teri King said she worries about longer-term effects.

“We're still going to have nutrients running into Puget Sound that are still going to be fueling phytoplankton,” she said.

With fewer filter feeders like clams and oysters to slurp up plankton, harmful algae might be able to bloom unchecked, which could threaten the sound’s water quality and lead to fish kills.

“We certainly hope this isn’t the new normal,” Dethier, the Friday Harbor Laboratories director, said. “We hope that for people, for their own survival, and for marine life as well.”