Copper versus salmon: Why an Alaska mine matters in the Northwest

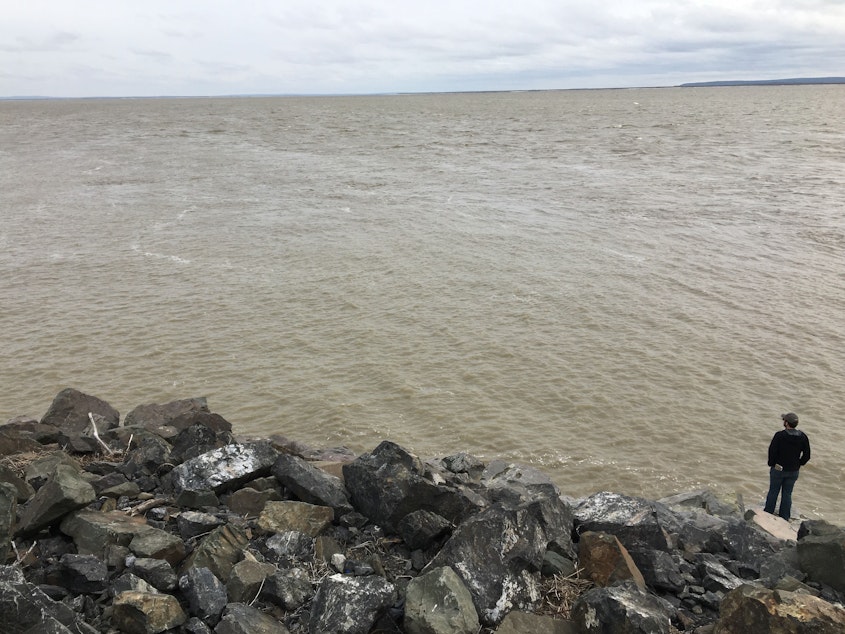

Hidden in the photo below is the story of an epic clash.

Like many things Alaskan, what’s at stake is grand on a scale that can be hard to grasp, especially for people from “Outside” (Alaskans' term for the rest of the United States).

Hidden beneath that soggy expanse of southwestern Alaskan tundra is the Pebble deposit, one of the world’s largest undeveloped reserves of copper and gold.

The remote tundra plateau also sits at the headwaters of two river systems, the Kvichak and the Nushagak. They are key arteries of the Bristol Bay watershed, the sockeye salmon capitol of the world.

More than half of all the sockeye caught in the world come from Alaska’s Bristol Bay.

Sponsored

WATCH: Dense clouds of Bristol Bay sockeye salmon crowd Alaska's Little Togiak Lake in August 2019. Video by Daniel Schindler / University of Washington.

The clash reaches far beyond Alaska.

The Pacific Marine Expo in Seattle is the annual trade show and community gathering for the fishing industry on the West Coast. Thousands of people wander among acres of booths for boats, sonar systems, life rafts—basically anything to do with commercial fishing.

But this year, the keynote event for this whole shebang wasn’t about fishing at all. It was about a mine.

“I wish we were talking about happier things, but this is necessary,” emcee Jessica Hathaway, editor in chief of National Fisherman magazine, started off the six-member panel.

Sponsored

The panel spoke about, and mostly railed against, the proposed Pebble mine.

“This pit will continue to generate acid mine drainage for centuries, millennia into the future,” University of Washington fisheries biologist Daniel Schindler told the crowd.

The Pebble mine's possible impact on water and salmon has been a bogeyman for the fishing industry in Alaska and beyond for more than 20 years.

“There are quite a few of us, especially from Washington, that spend our summers in Bristol Bay,” set-netter Elma Burnham of Bellingham said.

Every summer, she and a few thousand other people head up from Washington and Oregon to Bristol Bay to work on the boats and in the canneries that handle sockeye.

Sponsored

Set-netters catch salmon in gillnets that they stretch between a small boat and the often-muddy shoreline. Other gillnetters call them "mud farmers."

“It's a big part of my income just because Bellingham isn't known for paying high salaries in the nonprofit sector,” Burnham said.

Most of the year, she runs a seafood festival in Bellingham.

People do still fish for salmon in Washington, but there just aren’t many fish like there used to be or like there are today in Bristol Bay.

Sponsored

“We really have a last chance with some of the Alaska fisheries,” Burnham said. “We missed our chance in Washington. So if we can have any chance left in Alaska, we might as well do all that we can to protect it.”

“These last few years in Bristol Bay have been absolutely amazing,” Bellingham gillnetter Michael Jackson said.

He’s part of a community in Bellingham that makes much of its living fishing Bristol Bay. So are his two sons, who now have their own fishing boat after learning the ropes on their dad’s, the Lovely Kelley J, named for their mom.

Five years in a row now, more than 50 million sockeye salmon have returned to Bristol Bay.

In 2018, an all-time high of more than 62 million adult fish returned to the bay, the biggest sockeye run since record keeping began in 1893.

Sponsored

(If those numbers don't impress you, here's some context: The vast Columbia River basin, in its pre-damming, pre-logging and pre-overfishing heyday, once supported an estimated 10 to 16 million salmon and steelhead a year. The 2019 forecast for the Columbia is 1.2 million returning salmon, many of them pumped out by hatcheries.)

“We are the largest sockeye producer in the world because we have a pristine habitat,” Jackson said. “This is a treasure.”

I asked Jackson why people in Washington, with an economy driven by online services and airplane sales, should care about a bay 2,000 miles away on the Bering Sea.

“Washington should care because we're part of a world,” Jackson said, “and the world should care because there are no more places like Bristol Bay.”

Bristol Bay’s natural wealth hasn’t always translated into wealth for its people.

“These communities exist in what is potentially the richest fishing grounds in the world for salmon. Yet they are dying or have died. To me, that’s failure,” said Brad Angasan, a senior vice president with the Alaska Peninsula Corporation in Anchorage.

The Alaska Native corporation is owned by shareholders from five Bristol Bay villages, including South Naknek — Angasan’s childhood home — population 47 and shrinking.

Bristol Bay’s salmon fishery collapsed in the 1990s, forcing many locals to sell off their valuable commercial-fishing permits.

“All of those permits went to people who lived down in Washington and just generally outside of the region and even the state,” Angasan said.

People from outside Alaska, mostly Washingtonians, landed more than half of the record 231-million-pound haul of sockeye from Bristol Bay in 2018, according to Alaska’s Commercial Fisheries Entry Commission.

Permits for the now-booming Bristol Bay sockeye fishery sell for six figures. Less than one-fourth of those pricey permits are held by Bristol Bay locals, and only one in seven jobs processing that fish is held by someone from Bristol Bay.

The Bristol Bay Economic Development Corporation, a nonprofit funded by the fishing industry, offers loans and other aid to help locals buy fishing permits. It will even give $35,000 to any Bristol Bay resident to upgrade their fishing boat.

But the assistance hasn't turned the tide: The number of locals working in the fishery keeps declining.

The situation has left some Bristol Bay residents hoping that a big mine can turn their fortunes around.

Despite vocal opposition from some shareholders, the Alaska Peninsula Corporation signed a deal last year to help the Pebble project build a road to the mine site and to share in the profits if the mine does open.

“If our villages were healthy and sustainable and they had commerce, would we be in this position right now?” Angasan asked. “Probably not.”

If you take a small plane across the rugged, roadless expanse southwest of Anchorage, after about 100 miles, you’ll hit Alaska’s biggest lake, Lake Iliamna.

Picture a lake about the size of Puget Sound, but so clean, people still drink straight out of it.

The 75-mile-long lake is just one of a couple million lakes in the Bristol Bay watershed.

Like other Bristol Bay lakes, it teems with sockeye. It’s also one of the few lakes in the world that harbors freshwater seals.

The lakefront village of Iliamna is a short helicopter ride to the Pebble mine site. It has become a hub for the Canadian mining company and its consultants as they do initial fieldwork to develop a mine. Feeding, housing and protecting Pebble workers has brought infusions of cash to Iliamna.

21 secs

A helicopter departs for the Pebble mine site from the Pebble Partnership hangar in Iliamna, Alaska.

21 secs

A helicopter departs for the Pebble mine site from the Pebble Partnership hangar in Iliamna, Alaska.

“This issue has divided families, close friends, and it's still going on,” Iliamna Village Councilmember Lary Hill said.

“With some families it's understood that you don't discuss it,” Hill said.

The village council has not taken a position on the nearby mine project.

Hill is a retired schoolteacher. He also spent a decade working as a “bear guard” for the Pebble project.

“We have a lot of bears in the area,” he explained. “Management was worried about [consultants] getting mauled or hurt in some way or the bears getting killed.”

So the mining company hired locals as armed guards for the consultants doing preliminary fieldwork.

“All the years I was there, we never discharged a weapon once at any animal," Hill said. "We just moved everybody away.”

Even though he spent years working for Pebble, Hill said he’s torn about the mine project.

“Keeps me awake at night,” he said. "It could be worst-case scenario. It could be the best thing for our area.”

He’s worried about what would happen to salmon and other native foods if there’s a spill of toxic mine waste. But he’s also worried about Iliamna without the mine.

“There are very few jobs here. I'm worried that our villages are going to just kind of dry up and go away.”

Hill said his three grandsons have all moved away from Iliamna, current population about 150.

“People are kind of emotional about this thing because you feel deeply for the land,” he said.

“We don't believe mining will kill everything like everybody tells everyone,” Iliamna Development Corporation CEO Lisa Reimers said.

Her Anchorage-based company works for Pebble. She grew up in Iliamna.

Her childhood home is now a dormitory for mine technicians. An adjacent building houses a cafeteria for them.

“The villages that are the closest see the benefit of Pebble," Reimers said. "They see the jobs. They see the economy it brings to the village.”

“Whatever you say about our community, please be respectful,” Hill asked a group of visiting journalists. “We're just trying to live.”

Native communities farther downstream, where people are less likely to get jobs working for the mine, tend to have a more negative view of Pebble project.

The Bristol Bay Native Corporation surveyed its shareholders from 31 villages in July: 76 percent opposed the mine, and 15 percent supported it.

“It threatens to take away all that we enjoy, the salmon, our pristine waters,” Igiugig Village Council president AlexAnna Salmon said. “Here in Igiugig, we enjoy a high quality of life.”

About 70 people live in Igiugig, where Lake Iliamna empties into one of Bristol Bay’s main salmon rivers, the Kvichak.

In this isolated outpost on the tundra, street signs are in Yupik. Gas is $5 a gallon.

The school mascot is tiny but fierce: the No-see-ums.

Wild foods like salmon, caribou and berries remain important, and traditional ways have enjoyed a revival.

“We have a right to maintain this ancient connection to our homelands,” Salmon said.

Like other mine opponents, she has a litany of arguments against the mine: wetlands and salmon streams that would dry up, a new road, and new ports to be built on wild lakeshores and the Gulf of Alaska seashore.

The mine would operate an ice-breaking ferry year-round, disrupting villagers’ snowmobile travel across the lake for winter hunting or socializing.

“We've given up so much already, I feel like we've been pushed to the limits,” Salmon said. “Because we will feel the impacts on a disproportionate level than anyone else.”

“They cannot answer that question of how will you protect for our way of life,” she said.

“I appreciate that AlexAnna and others’ fears are real, but I do not believe that they're based in science,” Pebble CEO Tom Collier said.

Collier stands to make a $12.5 million bonus if the mine is approved in 2021 and a $10 million bonus if it’s approved in 2022.

Beyond the financial benefits, mine backers say Pebble’s main output, copper, is a necessity for the world’s urgent push to adopt climate-friendly technologies like wind turbines and solar panels.

The World Bank has forecast that the world will need as much copper in the next 25 years as has been mined in the past 5,000 years.

“Human beings on this planet, we do need mines,” Rick DelKittie Sr. of Anchorage said. “Only some places, they should not build them."

Before moving to Anchorage, DelKittie was a member of the tribal council of Nondalton, a village about 15 miles east of Pebble. The council opposes the mine.

Collier, who was a political appointee in the U.S. Department of the Interior during the Clinton administration, disputes that there is any conflict between Pebble and salmon.

“We’re not going to harm the fishery,” he said. “We are such a small little speck on that enormous landscape.”

Compared to the Bristol Bay watershed — an area the size of Ohio with a population of just 7,000 — any mine would be tiny.

The main question is what impacts would spread beyond the mine’s physical footprint.

“There won't be an accident. And if there is an accident, it won't have any significant impact,” Collier said.

“There is going to be an accident,” DelKittie said. “It's not if — it's when.”

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is finalizing its environmental impact statement on the Pebble project.

The current draft, relying almost entirely on science conducted by Pebble, concludes the mine poses zero risk to the Bristol Bay fishery.

“It’s not zero. There’s no way it could be zero,” University of Washington biologist Daniel Schindler said. “That ignores realities like the fact that water flows downhill and a spill that occurs at the top of the watershed has a likelihood of affecting ecological processes at the bottom of the watershed.”

Science is another connection between Washington state and Bristol Bay.

The University of Washington has had a fisheries research station on Lake Nerka since 1947 — about 30 years before the chain of wilderness lakes along the Wood River was designated Wood-Tikchik State Park, now the nation’s largest state park. It’s more than 100 miles west of the Pebble mine site, on a different river system, and would not be directly affected by any pollution or disturbance from the mine.

Schindler has spent the past 23 summers inhabiting and studying this pristine sockeye factory of an ecosystem.

Last winter, back in Seattle, he taught Fisheries 513C, a graduate-level class focused on the Pebble mine’s environmental impact statement. He encouraged students to submit public comments on scientific shortcomings they found.

“I think it's our obligation to advocate for credible science," Schindler said.

He called the industry-funded claim that the mine won’t harm fish downstream "patently false.”

The Army Corps of Engineers expects to finalize the environmental impact statement by March and issue a final decision on the Pebble mine by June.

It's unlikely the Army Corps would stop the project: The agency rejects about 1 percent of permit applications a year, according to David Hobbie, the Corps’ top regulator in Alaska.

People on both sides of this 20-year controversy agree that it’s been exhausting.

With lawsuits expected to follow the Corps’ decision, the battle over the Pebble Mine could continue for a long time.

Reporting from Alaska made possible in part by the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources.