City officials have known about cracks in West Seattle Bridge since 2013

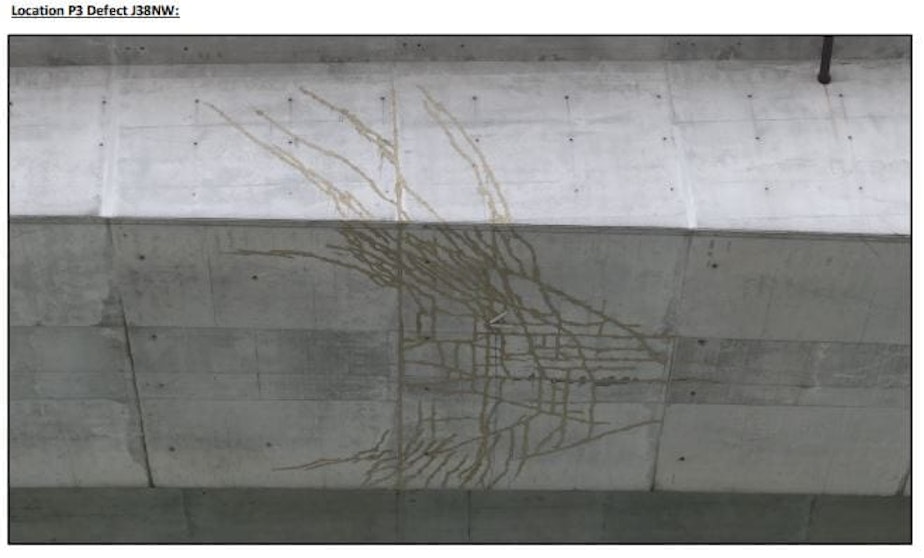

Though they had spread dramatically in recent weeks, the cracks that led city officials to suddenly close the West Seattle Bridge Monday were nothing new.

Bridge inspectors first saw the series of cracks in concrete beneath the main span’s deck back in 2013.

Federal regulations require that highway bridges be inspected every two years. After city inspectors found cracks on the underside of the bridge in 2013, they started inspecting the structure, which was built in 1984, annually.

In 2019, city crews filled the cracks with epoxy, a stopgap measure that failed to keep the cracks from expanding.

Heather Marx with the Seattle Department of Transportation said the cracks were only “mildly worrying” until an inspection in December 2019 revealed them to be growing.

"It was significant growth, but it wasn't growth to the point where where we needed to shut down the bridge," Marx said.

In late February, an engineering consultant recommended that the city consider restricting traffic on the bridge to ensure public safety.

Sponsored

The more load is put on a bridge, the more likely it is to suffer damage. Still, the benefits of lightening traffic on a bridge as large as the West Seattle Bridge are limited: 80% of the bridge's total load comes from its own weight.

Another inspection on March 6 showed the cracks growing faster.

More than a week later, the Seattle Department of Transportation had not notified elected officials or the public of the worsening problem.

“Last week, we were actually preparing a briefing to give to the mayor and the city council about how we wanted to plan to reduce the traffic load on the West Seattle Bridge because we were concerned about it,” Marx said on Wednesday.

On Monday, March 23, another inspection showed "exponential growth" in the length of the cracks snaking along the bridge's underbelly.

Sponsored

“Overnight, we decided, ‘Oh my God, we can't just reduce the load, we have to take the traffic off entirely,’” Marx said.

March 23 also appears to be the first time that Seattle officials informed the public of the lengthening cracks beneath the most heavily traveled city-owned road, 150 feet above the Duwamish Waterway.

In normal times, the bridge carries 100,000 vehicles and 14,000 bus riders daily.

During the coronavirus pandemic, traffic volumes have fallen by half, according to Seattle Department of Transportation director Sam Zimbabwe.

Sponsored

“In some ways, I guess, it’s fortunate that traffic volumes are so low,” Mayor Jenny Durkan said Monday.

Hairline cracks are not unusual or necessarily problematic in concrete bridges.

But as cracks get bigger, they can let water seep in and corrode the hidden steel that really holds a bridge together.

“The bigger problem is typically going to be damage to the steel inside,” University of Washington civil engineering professor John Stanton said.

Inside the concrete girders of the West Seattle Bridge and others designed like it are steel tendons that were put under tension – pulled taut– during construction.

Sponsored

Those taut tendons serve to push the concrete together like giant rubber bands. They help the concrete resist the gravity and other forces that could crack or otherwise pull it apart.

“In most cases [of] cracked concrete, you're not too bothered about the concrete not operating properly,” Stanton said. “You are worried about the steel inside becoming corroded.”

Stanton said cracks are often symptoms of other internal problems that epoxy won’t address.

Transportation officials are still determining how to repair the bridge and how long it will be closed. They don’t expect any quick fixes.

Sponsored

“It is not something that will take weeks,” Zimbabwe said. “It will be a longer-term closure.”

The West Seattle Bridge was designed to last 70 years. It’s half that age.