Are you a loud talker? You might be a superspreader

“Say it, don’t spray it,” goes the old playground taunt. That’s easier said than done, given the invisibly-small droplets we emit when we talk or even breathe.

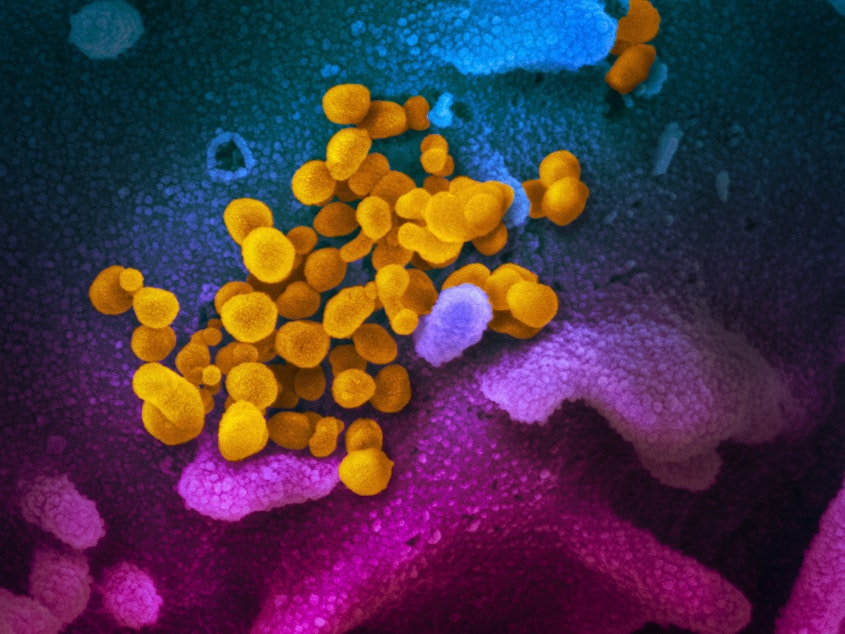

One minute of loud speech generates more than 1,000 virus-containing droplets, according to a new study from the National Institutes of Health.

Those tiny, aerosolized droplets stayed airborne 8 minutes or longer, unlike the larger bits of saliva that tend to drop quickly to the ground.

“Normal speech generates airborne droplets that can remain suspended for tens of minutes or longer and are eminently capable of transmitting disease in confined spaces,” the researchers write in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

How much of a transmission risk that these tiny, long-lived Covid-19 aerosols pose -- compared to larger, short-lived droplets emitted in coughs and sneezes -- is a topic of ongoing debate and study.

The new study of what happens when we speak could help explain how more than 50 people came down with Covid-19 after attending a choir practice in Skagit County.

Sponsored

The federal researchers set up a device to see the tiniest droplets by illuminating them in a sheet of green laser light. Then a researcher repeated one phrase – “stay healthy” – for 25 seconds into a chamber in the device.

They chose that phrase because the “th” sound in “healthy” generates lots of spray.

Attaching an iPhone to the laser device, they filmed the normally invisible particles bouncing around the chamber for more than an hour.

“There is a substantial probability that normal speaking causes airborne virus transmission in confined environments,” the researchers concluded.

“This makes sense to me as a plausible mode of transmission for Covid,” University of Washington epidemiologist Janet Baseman, who was not involved in the study, said in an email. “If you think about it, coughing or sneezing is like speaking with propulsion, and coughing or sneezing is an established mode of transmission.”

Sponsored

“You do generate those types of particles when you speak. But does that translate to infectious risk?” infectious-disease specialist Amesh Adalja of Johns Hopkins University asked.

Adalja cares for coronavirus patients. He said many more healthcare workers would have fallen ill despite their protective equipment if Covid-19 spread by people’s ordinary breathing and talking, the way measles and tuberculosis can.

“People that basically enter a room after someone with measles has been in it can get infected,” Adalja said. “We're not seeing these types of stories.”

Virologist Emma Hodcroft of the University of Basel in Switzerland said the study, as well as Covid-19 outbreaks documented in restaurants, buses and call centers, suggested that groups in places with limited air flow could be at risk of infection.

“I'm concerned our 'opening' guidelines and restrictions may not be considering airborne microdroplet transmission,” she said on Twitter.

Sponsored

“My concern is that while a lot of attention is going towards keeping 2 meters apart and wiping doorknobs and surfaces, little is focused on people in enclosed spaces,” Hodcroft said.

“Anything under 5 microns or so will stay airborne for a relatively long time in indoor air,” Portland State University environmental engineer Richard Corsi said in an email. “Imagine 10 people all speaking at once in a classroom, courtroom, etc.”

“To me, this further elevates the 6-foot rule and recommendations for face coverings,” Baseman said.

Not all speech is equally risky.

Sponsored

University of California, Davis, researchers found last year that the louder someone talks, the more droplets they spray.

“Speaking loudly yielded on average a 10-fold increase in the emission rate compared to speaking the same series of words quietly,” they wrote in the journal Scientific Reports.

Some people, for reasons that are unclear, are “super-emitters,” whose voices generate 10 times more droplets than other people’s at the same loudness.

“We do know that singing does pose a special risk, especially if somebody is infectious and symptomatic, and that that's an activity that really has to be done with caution,” Adalja said.

The Skagit choir case

One singer appears to have sickened 52 others during a 2.5-hour choir practice in Skagit County on March 10.

Sponsored

At the time, the county north of Seattle had no confirmed Covid-19 cases. County officials recommended people over 60 avoid large public gatherings, without specifying what “large” meant. State officials were warning people to avoid gatherings of 250 or more.

Skagit Valley Chorale, whose members are mostly women over 65, decided to hold its weekly Tuesday evening rehearsal after urging anyone showing symptoms of any illness or uncomfortable with attending to stay home.

“At all times, the Chorale followed the guidance of local and state health authorities in decision-making processes,” the group posted later on Facebook.

After learning of the outbreak, county health officials interviewed all 61 attendees and traced their steps to find the outbreak’s origins and contain it.

“Members had an intense and prolonged exposure, singing while sitting 6–10 inches from one another, possibly emitting aerosols,” the health officials wrote in a May 15 report, published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, on the "superspreading event."

No one reported having physical contact with other choir members, though many shared cookies and oranges during a 15-minute break. They also congregated as they returned their chairs to a rack as practice wrapped up.

By the end of the evening, 52 of 60 attendees, not counting the probable Patient Zero, who reported having “cold-like” symptoms at the time, had been infected.

By the end of the month, two were dead.

"Our group feels like a family, so you might imagine our grief," the chorale posted on Facebook.

Song and safety

As far back as the 1960s, scientists have investigated how singing might spread some diseases.

University of Texas researchers studying the spread of tuberculosis found that singing produced a much greater proportion of tiny droplets – which stay aloft longer and are more likely to reach deep into the lungs, where they can spread respiratory disease – than talking did.

Half a century ago, those researchers said they would prefer “a world with tuberculosis to a world without song.”

“Better that people gather to sing together than to shout at one another, even if the droplets produced are smaller and therefore occasionally more dangerous,” they wrote in 1967, the year of the Summer of Love, in the American Review of Respiratory Disease.

In 2020, singers don’t have to choose between song and safety: many choirs now perform virtually.

The Seattle Girls Choir performing virtually on March 25, 2020