The racist practice of mispronouncing names

When Zuheera Ali walks into a coffee shop, she stands outside the door, opens her wallet, takes out her card, figures out exactly what she wants to order, and she reminds herself: ‘You’re Billy. You’re Billy.’

The barista doesn't believe her, of course. But they can’t do anything about it.

As her co-host Keya Roy says, "You can be whoever you want because you will never see this barista again."

In this episode of RadioActive Youth Media, Keya Roy and Zuheera Ali talk with author Ijeoma Oluo and each other about living in the United States with uncommon names. They also talk to Rita Kohli, a professor at University of California, Riverside, who has researched the effects of mispronouncing names on students of color.

Producer Medha Kumar has her name butchered constantly. Every time a teacher reads the attendance list and gets to her name, she knows they’re looking at her name because they’re squinting. It’s one of those super awkward moments.

Kumar remembers a time in second grade when she had to give a PowerPoint presentation in front of her class: “I was standing in front of my classmates and my teacher had turned on autocorrect. The first slide was just supposed to be my name, but was corrected to read ‘Media K-Mart.’ It was so embarrassing.”

Keya Roy says she has stopped correcting her teachers when they mispronounce her name. “At some point, it’s just futile,” Roy says.

Zuheera Ali says she was never one to let someone say her name wrong.

"My name is my identity, and allowing someone else to say it wrong is stripping me of that," she says. "I feel like as a woman of color, I’m expected to make these changes, especially when I’m at school. But asking me to make my name easier to pronounce is a very unfair way that I have to change."

Says co-host Keya Roy: “I always felt like by giving into that pressure to conform and allowing my name to be butchered, I was somehow making life easier for others...

"My name is a way to push me aside, and most of the time, the people who are doing this don't realize the damage they could be doing to my self-worth and sense of confidence."

Rita Kohli, the professor at University of California Riverside, has researched how mispronouncing names of students of color hurts them.

“We’ve found a lot of people feeling embarrassed — ashamed of their name, wanting to withdraw from raising their hand in class, and sitting on the edge of their seat during roll call so they can say their name before a someone else messes it up,” Kohli says. “There was a lot of anxiety and fear that came along with this.”

Ijeoma Oluo, author and leading voice on race in America, says her name is often used to discredit her.

"People will try to — as a blatant sign of disrespect — mispronounce my name or mock my name," Oluo says. "I get that on social media all the time."

Oluo says people on social media will "deliberately, wildly misspell my name to show to other people how serious must I be taken if I don't even have what they would consider to be a serious name. It's racist at its core to think that other cultures names are invalid. It's othering and purposefully disrespectful, and it's often used as a weapon against me."

She continues: "It's my name and I won't let anyone take that from me."

Research shows that having an uncommon name can cause anxiety and alienation. The racist practice of mispronouncing names has evolved from a long history of changing people of color's names to strip them of their dignity and humanity.

"The changing of people's names has a racialized history," said Kohli. "It's grounded in slavery — the renaming during slavery — renaming Americanization schools for Latinx communities and indigenous communities, and so there is a lot of history that's tied to this practice that is directly tied to racism."

This history is painful even though it seems so far in the past, Zuheera Ali says. But history is not removed for many African-Americans, many of whom don't know their ancestors' names and carry the names of slave owners.

Getting someone's name right is a simple sign of respect — of them as people, and where they come from, these podcasters say.

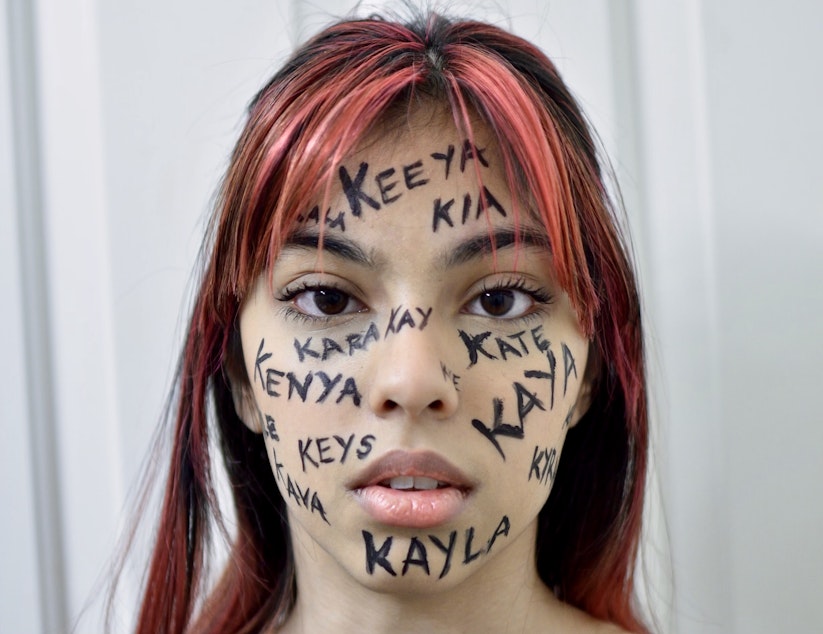

"Interrupting someone to say, 'It's Keya, not Keeya,' isn't me being irritating, it's me putting my foot down against a vehicle of racism, and then in turn, creating an environment in which owning your name is the norm, not the exception," Keya Roy says.

This story was created in KUOW's RadioActive Advanced Producers Workshop for teenagers, with production support from Mary Heisey. Edited by Caroline Gomez.

Find RadioActive on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and on the RadioActive podcast.