Baby oysters can't build healthy shells in Washington's acidified waters

Oysters are one of the iconic foods of the Pacific Northwest. But their survival is under serious threat thanks to ocean acidification, sometimes called the “evil twin” of climate change.

Local shellfish growers are seeing the devastating impacts on oysters and other shellfish.

Since 1989, the hatchery at Taylor Shellfish has grown billions and billions of oyster larvae. Like any other farm, it's had its share of failures — times when large numbers of oysters would die for an unknown reason. But things usually bounced back.

Then, in the 2007-2008 season, those failures became the norm.

“We didn’t have any oyster larvae,” recalled Bill Dewey, the company’s director of public affairs. “Our production was down by about 75 percent.”

Soon, they learned that other growers on the West Coast were having the same problem. Dewey said they knew something serious was going on.

“We had an oyster seed crisis. There was no seed for farms up and down the West Coast for the 2008-2009 time frame,” he said.

Sponsored

At first they thought it was bacteria killing the oysters. But even after thoroughly cleaning their tanks and developing a filter system to remove the bacteria, the oysters continued to die. Around that time, Richard Feely, a scientist at NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle, contacted the growers with a recent finding.

“He came to us and said, 'Here’s what I think might be going on.' So we started looking at the water chemistry. Lo and behold … this was carbonate chemistry. And the effects of ocean acidification were killing our oyster larvae.”

Ocean acidification happens when seawater absorbs carbon dioxide over time, reducing the water’s pH levels. It makes it harder for baby oysters to build their shells.

Sponsored

We’re at Taylor’s hatchery in Dabob Bay, where the oysters and other shellfish start their young lives. Dewey pauses at one of the many tanks in the hatchery. It's filled with water and millions of oyster larvae no bigger than the diameter of a strand of hair. This is a crucial stage of the oyster’s young life.

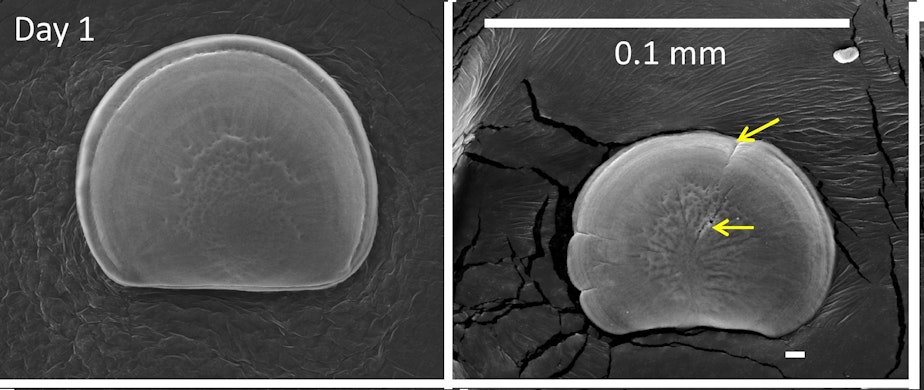

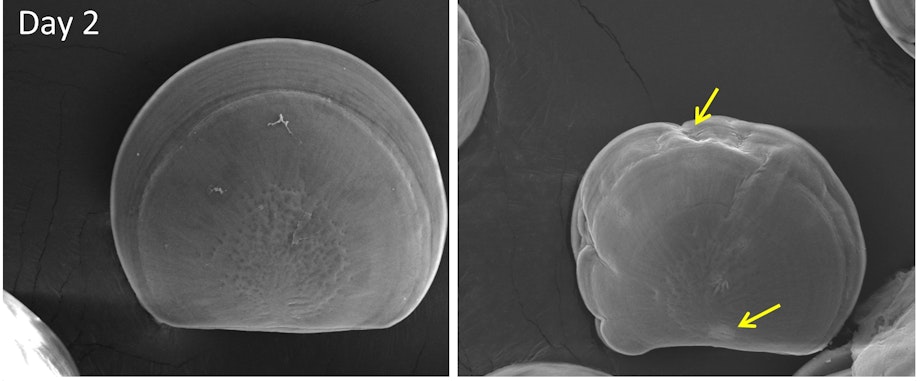

“In the first 48 hours of life, that baby oyster has got to do two things: it’s got to build a shell and it’s got to build this organ that it feeds with and swims with called a vellum," Dewey said.

When the water is too acidic, the egg becomes deformed and dies. It's used up its limited energy building a shell, and there’s none left to build its vellum.

When they realized that their baby oysters were dying, growers sounded the alarm. Lawmakers in Olympia took notice. Before Governor Chris Gregoire left office in 2011, she created a Blue Ribbon Panel to address the problem. The group’s work has since been expanded.

Jennifer Hennessey, senior policy advisor to Governor Jay Inslee, says ocean acidification is happening faster here than in other parts of the country.

Sponsored

“Because we have upwelling on the West Coast of the United States, that brings up corrosive waters that mix with the surface waters. So we are seeing those changes quicker than say the East Coast of the United States or the Gulf of Mexico.”

Hennessey said projections show that changes are coming even more rapidly in the next 30 years, so there’s a small window to address these problems.

Sponsored

In the meantime, shellfish growers like Taylor Shellfish have found a workaround that deals with the issue in the short term. Bill Dewey displays a large plastic drum fitted with a plastic tube. It's part of a pump system. “This noise you hear is a peristaltic pump that’s injecting sodium carbonate into the water," he said.

A researcher in Oregon created a special device that gives water readings in real time. It has allowed growers to adjust the hatchery water. “What this peristaltic pump is doing is automatically changing that water chemistry,” said Dewey, “adding carbonate ions to the water so our baby oysters can make their shells again.”

Dewey said the tool has improved the growing conditions for baby oysters. But once they’re out in the farms and tidelands, it’s up to nature.

Dewey said that’s where the public’s help in reducing carbon emissions comes in. But that's a more complicated fix.