70 percent of people who died in Washington and Oregon jails hadn't been convicted

When Jeremy Lavender came back from a 15-month Army deployment in Iraq to live with his wife and new baby, “he wasn’t the same person,” according to Lavender’s ex-wife, Myra Shearer.

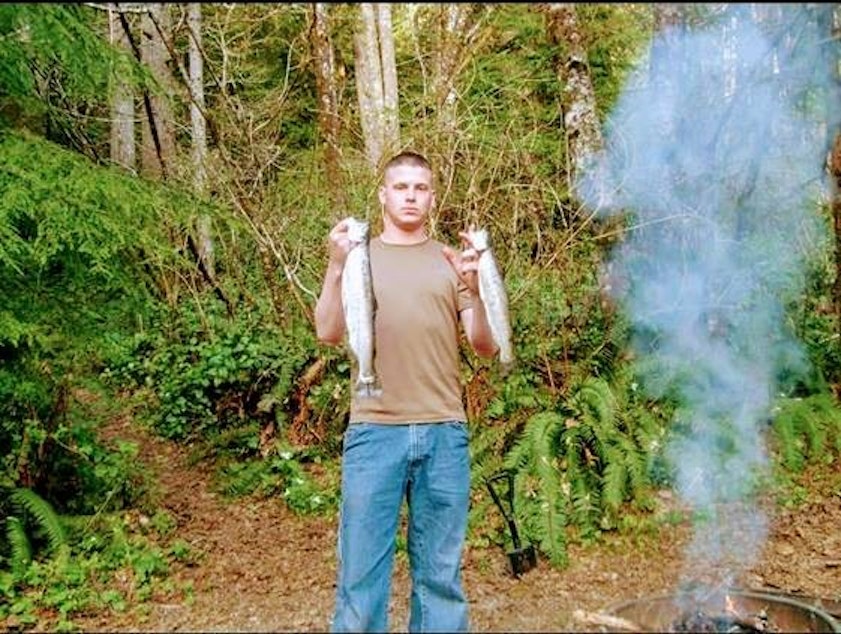

Shearer met Lavender when they were both just shy of 21. They loved hiking, fishing, taking trips to the ocean. Lavender was a great boyfriend — attentive, emotionally aware. Shearer said she was the only person he let touch his rebuilt, teal green Camaro, his “baby.”

The couple got married in 2006 while Lavender was home on leave. Shearer had found out she was pregnant.

“We were good,” Shearer said. That would change by the time Lavender was back home from the Army full-time.

At their home in Yelm, Washington, Lavender didn’t talk much about what happened in Iraq; he just became withdrawn. “As soon as he came home from work, he'd sleep on the couch,” Shearer remembered. “He’d get up and eat dinner and then he'd go back to the couch.”

Shearer said her ex-husband would go into what she described as trances. “He was almost in another world, where it was bad,” Shearer said. He would disconnect from reality and scream at his family.

Shearer didn’t recognize it then, but Lavender would later be diagnosed with both post-traumatic stress disorder and a traumatic brain injury. Lavender also started using drugs to cope, and like more than one in five veterans with PTSD, developed a substance use disorder.

Shearer and Lavender separated in 2007 and eventually divorced. By 2011, Lavender was living on disability and without effective treatment. Over the next several years, various court documents would describe him as “transient” or “homeless.”

In 2017, Chelan County police arrested Lavender after he was accused of shoplifting. A week later, he hanged himself in a jail cell.

Lavender’s story is not unique — a person with worsening mental health and little to no income who ended up in county jail and ultimately died. He was just one of the 214 people over the past decade who died after they were booked into a Northwest jail, even though they were not yet convicted of a crime. That’s according to data compiled by OPB, KUOW and the Northwest News Network.*

Read more: Northwest jails' mounting death toll

Across Oregon and Washington, at least 70 percent of the inmates who died since 2008 were awaiting trial, rather than serving time.

“The bottom line is that jails are not the right place for a person in a mental health crisis. They aren't set up for the kind of therapeutic environment that you need in order to be able to meaningfully help someone in a mental health crisis,” said attorney Christopher Carney, who has successfully sued Washington over the treatment of inmates with mental illness in jails. “I'm sure that in many cases they can and should do more.”

O

n Sept. 3, 2017, Lavender walked out of a Walmart Supercenter in Chelan, Washington, with $230 worth of electronics stuffed under his clothes.

Police, who had been called by the store’s loss prevention officer, stopped and searched him. Along with the electronics, they found a baggie of 17 prescription pills, a small rock of meth and two grams of heroin, according to their report. They sent Lavender to the Chelan County Jail.

Deceased Pretrial Detainees Held on Drug Charges or Misdemeanors

At least one in five people who died in pretrial detention were held on misdemeanors. At least one in five were held on charges that included drug or alcohol. In some cases, it was both.

Tony Schick, OPB. Source: Staff reporting by OPB, Northwest News Network, KUOW.

A Chelan County judge consulted a risk assessment tool to set release conditions for Lavender before his trial. Based on his past criminal history, which included similar low-level drug charges and violating a no-contact and temporary restraining order with his former girlfriend, the assessment labeled Lavender a “high drug” risk. That meant the court suspected he would likely use again if he was out of jail. The judge set bail at $5,000 for three counts of drug possession, felony charges in Washington.

Civil liberties advocates have long expressed concern over jailing people on low-level crimes that have root causes of mental illness, drug addiction or lack of stable employment.

“[These drug charges] wouldn’t have even been a crime in an ideal world,” said Jaime Hawk, legal strategy director at the ACLU of Washington. “Hopefully, a focus for [Lavender] would be connecting him with community-based services and getting him the help he needed instead of getting locked up in a county jail and deteriorating.”

Washington’s court rules dictate that people should be released in non-capital cases where they’re unlikely to commit a violent crime or intimidate witnesses. If a person poses a flight risk, courts are supposed to impose the least restrictive option available to get that person back into court.

But too often, Hawk said, courts rely on bail as that option, leaving people in jail with a bill for release they can’t afford.

“Most people in jail are ill or disabled in one way or another,” said Rep. Roger Goodman, D-Kirkland, chair of the Washington House Public Safety Committee. “They really need therapeutic care.”

According to the database created by OPB, KUOW and the Northwest News Network, at least one in five people who died in pretrial detention in the Northwest was held on misdemeanors. At least another one in five people was held on charges involving drugs or alcohol.

But in order to divert people from the criminal justice system, alternatives like therapy and treatment must be available, Goodman said. Too often, those alternatives don’t exist.

“We need to decriminalize mental illness and we need to decriminalize substance use disorder,” Goodman said. “People who are suffering in crisis should not be in jail and that's not the sheriff's fault. We don't have the community-based infrastructure for behavioral health.”

The link between pre-trial detention and higher suicide rates is well established. A 2008 meta-analysis of risk factors for suicide in incarcerated people found that being in custody before a trial carried four times the risk of suicide compared to people convicted of crimes and serving sentences. Being placed in a single cell increased that risk even more.

One reason for the deaths can be the uncertainty of those circumstances; pretrial detention can exacerbate underlying mental health problems if treatment isn’t available, according to Dr. Seena Fazel, lead author of the 2008 paper and a researcher who’s studied suicide in incarceration for the last 15 years. Another reason relates to the effects of substance withdrawal.

“What we know from lots of research is people with severe mental illness, bipolar or other psychoses, are going to prisons and they’re not getting the basic standard treatment that you’d get in the community,” Fazel said.

Letting inmates connect to services in the community while they await trial could allow them access to help instead of having their mental or physical health deteriorate in jail, advocates say.

The limited data available paints a stark picture of the issue statewide: On any given day, county jails across Washington are holding an estimated 4,700 people who might qualify for release and pretrial services, according to a 2019 analysis from the Washington state auditor. Releasing those inmates while they await trial would save between $6 million and $12 million a year, the auditor estimated. Oregon also has a government task force on pretrial reform, but has not released a similar statewide cost analysis.

L

avender was awarded an Army medal for valor he displayed while in combat. But Tina Lavender, Jeremy Lavender’s mother, said she found journals after her son died that described him struggling with what he had seen and done overseas.

“He was really dealing with the killing he had to do and it was not sitting right with him,” Tina Lavender said. “He was raised in a very kind, Christian environment, so it kind of went against everything he was taught to do.”

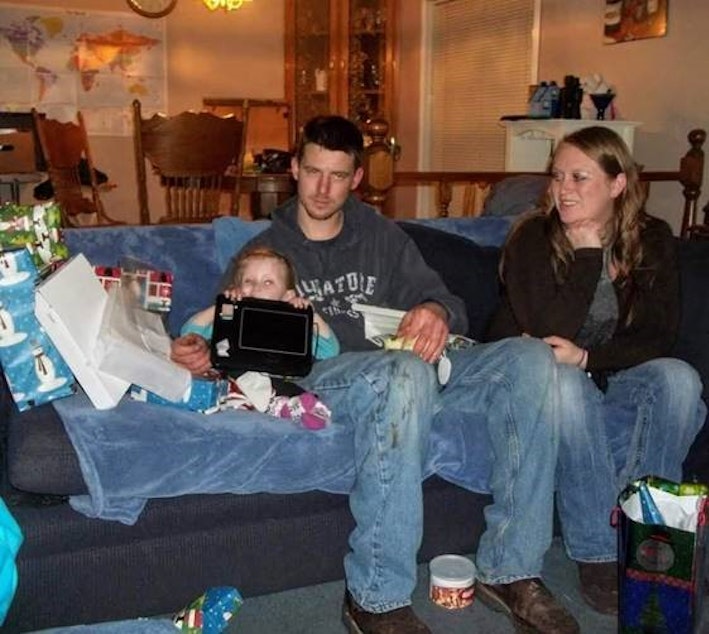

After he split up with Shearer in 2007, Jeremy Lavender met a woman named Amy DeHart the following year. Within four months, she was pregnant, but the two got to know each other well over the next two years, DeHart said.

Lavender loved to get up at dawn and take her fishing, even when DeHart was six months pregnant. And after she gave birth, DeHart said Lavender initially helped take care of their daughter, who was born with spina bifida.

But Lavender’s behavior worsened as the relationship continued. DeHart said he became unreliable, and she now believes he may have been making meth in the garage. Lavender, too, became violent on a couple of occasions toward DeHart. She said he threw her against a wall and threatened to kill her if she left with their daughter. DeHart obtained a no-contact order.

Lavender violated that order by constantly texting, showing up at her home and threatening to hurt himself, DeHart said. Nevertheless, she and Tina Lavender tried repeatedly to get him into treatment, with no success.

“Me and his mom went crazy trying to figure out: What are we supposed to do? We don't know what else to do,” DeHart said. “He didn't care about what we had to say. He was really bad into it.”

Sometimes, both his mother and DeHart wished police would arrest him — just to keep him and others safe. In those circumstances, Tina Lavender and DeHart said, police did nothing.

“I have heard that story a number of times,” said Carney, the attorney who sued the state of Washington. “It's a sad commentary on the level of community-based care that we give people in mental health crisis.”

Because of the lawsuit Carney helped settle, called the Trueblood case, he and others are working to pass legislation that allows police officers to divert people from jail at the point of arrest.

“In other words, instead of taking them to a jail, they can be transferred to an acute psychiatric care facility of one kind or another,” Carney said.

If the Trueblood legislation passes, diversion reform is likely to roll out immediately. Other statewide reforms dealing with the way people with mental illness are treated in Washington jails, however, are still years away.

The only time Lavender was able to see a psychologist before his arrest, DeHart said, was when he was put on an involuntary 72-hour hold. Even then, she said, he was released early.

Both Lavender’s mother and DeHart tried to find out what led to Lavender’s death at the Chelan County Jail, but were met with limited answers or silence, they said.

A

review of records in Lavender’s case shows jail staff struggled to manage his care and protect him as he tried to self-harm multiple times at the jail.

Two days after he was booked, according to a Wenatchee police investigation into his death, jail medical staff determined he was detoxing from heroin. Two hours later, he tried to hang himself.

Lavender spoke to the jail’s mental health coordinator after that. Still, jail staff reported he was banging his head against the wall of his cell. He was placed in a restraint chair for two hours, then put on a suicide watch with 15-minute checks.

“He would do anything he could to harm himself,” said one jail officer quoted in the report. A jail nurse also said that Lavender was “constantly asking to go to the hospital for treatment,” but she told him his care “was manageable in jail.”

At one point, the jail’s mental health provider asked an officer with a military background to talk to Lavender. It’s unclear from the report what effect that had, though the jail mental health provider reported Lavender had “appeared to be progressing well and doing better” as he opened up about his time in the war.

A day after he was placed on suicide watch, Lavender spoke to the jail’s mental health coordinator and said he no longer wanted to hurt himself, according to the report. He was taken off suicide watch and moved to a lower observation status. Two days later, he was taken off observation entirely.

On the seventh day of his stay at the Chelan County Jail, the jail’s mental health coordinator determined Lavender was not suicidal. On the eighth day, he had a seizure in a space called the “cage” while speaking to the coordinator and was taken to the emergency room. When he got back from the hospital, he had another seizure and was taken to a single cell in the booking area so staff could better keep an eye on him.

Staff observed him kicking the door of the cell. Four hours later, he strangled himself using jail linens that had been given back to him after he was taken off suicide watch.

Fazel, the suicide researcher, said that being housed in a single cell is one of the biggest risk factors associated with jail suicide. According to his 2008 research, prisoners placed in a single cell were nine times more likely to kill themselves than those housed in group settings.

The jail’s mental health coordinator told Wenatchee police that staff had discussed moving Lavender to a group cell, but that never happened. Wenatchee police concluded that jail staff “did everything they could do to help him, including keeping him close to staff to help monitor his health issues.”

Dr. Richard Cummins, a professor of medicine at the University of Washington who has served multiple times as an expert witness on jail deaths, said that county jails tend to lack adequately trained medical staff to deal with cases like Lavender’s.

“The assessment and treatment protocols guiding the correctional health care staff are outdated and substandard,” Cummins added.

Lavender’s family continues to wonder how he managed to die if officers were keeping a close watch, as the police report states. DeHart said she considered getting a lawyer to look into Lavender’s case.

When asked if Lavender received treatment for his PTSD and brain injury within the Chelan County Jail, a jail spokesperson said it was unknown if he received treatment for those specific conditions.

Lavender’s mother believes that such care is necessary.

“I do think there are certain cases, where, yes, they should be in jail and treatment is maybe not an option,” Tina Lavender said. “[But] I think in a lot of these cases, they could be treated. It may help some of them because they don’t deserve to just be thrown in jail.”

DeHart, a social worker, isn’t sure of the role that law enforcement played in Lavender’s death. But she is sure he didn’t get the help he needed. And she knows both of Lavender’s kids will grow up without their father.

“I think that the biggest thing is that, considering he was 100 percent disabled from the war, they should have some sort of hold,” DeHart said. “They should be able to go in there, and if so many people are reporting he’s mentally unstable, get him the help he needs.”

Northwest News Network's Austin Jenkins contributed reporting to this story.

*About the data

This analysis relied on death-in-custody reports filed with the federal government, requested from county jails in Oregon and Washington. This analysis excludes municipal and tribal jail facilities. Some counties provided full records, some provided redacted copies and some provided only basic information such as the number of deaths in a given year. Where possible, missing data was filled in using information from news reports, court filings, interviews and correspondence with law enforcement.

This dataset includes people who died behind bars and those who died after being taken from jail to health care facilities. It consists of both official “in-custody” death records and inmate deaths that did not meet that specific definition. The number of inmate deaths in this data is likely an undercount.

Each county was given a list of jail deaths compiled for years 2008-2018 to review for accuracy. All but two counties responded.

This data collection represents an ongoing effort and will be updated. A fuller explanation of data collection and methodology is available. If you have additional information about jail deaths in Oregon or Washington, or if you wish to obtain a copy of the data, contact Tony Schick at aschick@opb.org.