6 women accused a Seattle hip-hop artist of sex trafficking, allege police ‘did virtually nothing’

Editor’s note: This story contains descriptions of sexual assault.

T

he tape recorder clicked on. It was a cold night in early December 2020 when William Guyer, a veteran Seattle police detective, asked a young woman to recount months of alleged abuse and sexual assault.

“Can you start off with” — Guyer paused — “how you first came in contact with this suspect?”

Angelica Campbell, a 26-year-old artist from Chicago, had filed a protection order against Solomon “Raz” Simone, a Seattle hip-hop artist. Campbell told police that Simone had paid for her to move to Seattle earlier that year, then forced her into sex work at a strip club, starved, and assaulted her — all under the guise of a romantic relationship. When she refused to sell herself on the prostitution track on Aurora Avenue, she said, he evicted her from a house he owned.

“He’s really manipulative, and he’s been doing this for a while,” Campbell told Guyer and another detective that night. “I hope, I hope, I could help end it.”

Sponsored

Guyer, 60, had been a vice detective for much of his 22-year career in Seattle, and was familiar with Simone.

Since 2017, at least eight people — six women and the parents of two others — have told Guyer and Seattle police that Simone entangled women in a multistate sex trafficking scheme, with the promise of love and lucrative jobs, then coerced them into sex work in Seattle, New York, Portland, Las Vegas, and other cities. Some of the alleged crimes dated back to 2012.

They said Simone required them to earn $1,000 a day, which he collected, isolated them from their families, tracked their movements, and controlled their eating habits. Like Campbell, women told police that they had been choked, beaten, threatened, raped, and in some cases imprisoned for days in claustrophobic sleeping containers. Women told police that Simone forced them to call him “master,” “king,” or “God.”

Simone has denied these allegations. Police have never charged or arrested him for these alleged crimes.

Sponsored

S

eattle’s handling of the allegations against Simone illustrates the complexity and consequences of failing to police sex trafficking. Washington was the first state to criminalize trafficking nearly 20 years ago. But law enforcement across the state, including Seattle, has struggled to use these statutes effectively and train officers to recognize and help trafficking victims. Prosecutions involving adult victims also have a higher burden of proof than for minors, and must show evidence of force, fraud, or coercion.

Even as the MeToo movement has taken hold nationwide, Angelica Campbell and other women, who spoke with KUOW and The Seattle Times, said their hours of police interviews felt like screaming into a void.

And so, their complaints languishing with police, five women, including Campbell, filed a civil lawsuit in 2021 against Simone and his recording label, Black Umbrella, alleging that Simone conspired to “ensnare, imprison, and exploit” them for profit.

In September, they added the Seattle Police Department as a defendant for negligent investigation of their claims.

Guyer, who left Seattle Police over the city’s vaccine mandate, declined to answer questions for this story, citing a new job with the Kent Police Department. In a short interview outside his home in September, he said, “My career goal was always, ‘Fight the bad, protect the good, help the hurting.’”

Sponsored

“You know, every one of those girls I care about,” he said.

Seattle Police declined to make Police Chief Adrian Diaz available for an interview. In a statement, Seattle Police declined to answer questions about its investigation into Simone, citing the pending lawsuit.

It noted that trafficking cases are “often complex cases involving violent suspects, geographically expansive crimes, and victims without a support system. Seattle Police’s approach to these cases is trauma-informed and victim-centered.”

The FBI also has been investigating Simone’s alleged trafficking crimes since at least 2021 but has not taken action.

Sponsored

Ellery Johannessen, an attorney for the women, said he wants to determine whether the failures in the case are because of one detective, the police department, or a larger system failing to properly handle trafficking crimes.

Seattle Police “had actionable, credible information from multiple sources,” Johannessen said. “They did virtually nothing.”

A hearing in the lawsuit, involving Seattle Police’s efforts to be dismissed from the case, is scheduled for Friday. The city argues that state case law does not recognize claims for “negligent investigation” by police.

Even as women reported abuse, Simone’s star rose. He opened a seven-city tour with Macklemore and performed at music festivals. One of his music videos racked up more than 700,000 views on YouTube.

In 2020, Simone positioned himself as a leader of the Capitol Hill Organized Protest or CHOP, where videos showed him pulling a gun out of the trunk of his white Tesla.

Sponsored

Text messages show Seattle’s fire chief and the mayor’s office coordinated with Simone during the protests, adding authority to his self-appointed role. At the same time, the Seattle police gang unit wrote in an internal email that he was an “associate” of the Deuce 8 street gang and warned that he might be armed, department records show.

Simone has repeatedly denied that he harmed, confined, or trafficked these women, but did not answer multiple calls and texts for this story. In an interview with KUOW last year, he said the accusations are false and the women are trying to shake him down.

“It’s been a plan they put together years back,” Simone said. “The money’s on the line, and they’re using it like a class-action lawsuit.”

Paul Beattie, an attorney for Simone, said by email that neither he nor his client would discuss the case, adding, “At this point, these are essentially only allegations — not proven facts.”

I

n August 2017, Pearl, a 27-year-old living in Las Vegas, called and emailed Seattle Police, asking for help. She was pointed to Guyer. For more than a year, she and at least two other women were forced into sex work in the lucrative clubs of Las Vegas, 12 hours a day, seven days a week, by Simone, she told Guyer in an email.

“We are afraid for our lives,” she wrote.

KUOW is not using the names of several women in this story because of safety and privacy concerns. Pearl asked to be referred to by her stage name.

Pearl sent Guyer emails and text messages containing photographs and videos that supported her allegations, which are also referenced in court filings. KUOW and The Seattle Times also reviewed hundreds of additional images, screen shots, emails, text messages, and medical records, obtained in public disclosure requests and from Simone’s accusers.

Attached to the emails were copies of the protective orders Pearl and another woman, then 23, had filed against Simone in Las Vegas. Their handwritten allegations asked that Seattle police provide them protection from him.

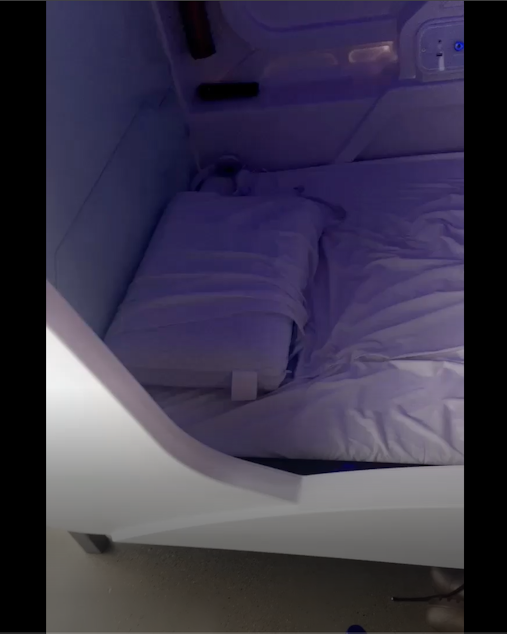

Handheld videos show Pearl’s alleged confinement in the Black Umbrella office — its Airport Way South location just two blocks from the police station where Guyer would later interview Campbell. One video pans over four white plastic sleeping pods, stacked two by two, roughly 6 by 3 feet in size. In another video, Pearl sits inside a pod, her blue-gray eyes puffy from crying, and her temple and cheek cut with self-inflicted red gashes.

Simone confined her in a pod for three days that spring after she begged him to let her stop stripping and prostituting in Las Vegas, she told Guyer and later described in interviews with reporters. While inside the container, she heard Simone and other men come and go. But he only opened the pod door to silence her screaming, she said.

The abuse she said she experienced had been ongoing for 18 months, since Simone first paid for her to come to Seattle, Pearl told Guyer in interviews and written testimony.

“He has choked me to the point of passing out. He raped me when I didn’t come home on time. He decided what I ate and drank,” Pearl wrote in protection order documents.

The demands to make money were so severe she developed a kidney infection. After surgeons placed a stent in her urethra, Simone raped her with the plastic tube still in her body, she said in interviews and told police.

“Thanks for all the info,” Guyer responded 13 hours later. “I’m out of the office for a few days but will start digging through this … Your [sic] doing a good job keep fighting!!”

Pearl offered to testify and put Guyer in touch with other alleged victims — including a teenager — but his responses became intermittent, email records show. In October, after Simone was added to the SXSW music festival in Austin, she emailed Guyer again with a link to Simone’s Facebook post:

“Looking for a girl for a video,” Simone wrote. “Doesn’t matter where in the world you are.”

After two months of silence, Guyer wrote back. He told Pearl that the case was unlikely to move forward unless the teen girl decided to go on the record.

“I am bewildered that our justice system cannot prosecute him unless you have underage testimony,” Pearl replied. “There has to be something we can do.” Guyer did not write back.

Public records obtained by KUOW and The Seattle Times show Guyer was, however, talking to Simone. In the fall of 2017, Guyer and another detective met with Simone at a Tully’s coffee shop, and Simone shared hundreds of text messages with Guyer, emails show.

Simone said in a December 2020 interview with KUOW that he showed police his communication with various women. “I talked to police officers,” Simone said, “and they just figured it was a mess.”

The case lay dormant for three more years.

For Pearl, her life contracted. In the weeks after she escaped her trafficker, security footage, obtained and reviewed by KUOW and The Seattle Times, appears to show him breaking into the garage of her apartment complex. Simone now knew she had ratted him out. And law enforcement wouldn’t help her.

Guyer’s lack of response to her allegations, she said, “put a nail in my coffin. It made me afraid to go out in the world for a long time.”

N

o trafficking case is simple. The criminal justice system favors sex trafficking prosecutions involving juvenile witnesses, experts say, in part because the burden of proof is lower. If a minor is involved in a commercial sex act, it is automatically considered trafficking because they cannot consent.

Sex trafficking is defined as an individual being recruited, purchased, harbored, or transported and then forced or coerced into sex acts for another person’s profit.

But for an adult, a prosecutor must prove there has been force, fraud, or coercion. That does not mean the adult isn’t a victim, but the evidence of harm — like signs of physical and emotional abuse that often leave little trace — must be explicit.

“Sadly, it makes a big difference as to whether something is pursued criminally or not,” said Meredith Dank, a professor at New York University and human trafficking expert. “There is a lot of evidence to show prosecutors are more likely to take a case if it is minors because it is easier.”

Guyer’s career has focused on cases involving teenage girls. His personnel file includes letters of gratitude from family members and praise for his “outstanding support” for Operation Cross Country, the FBI’s national campaign to rescue children forced into prostitution.

In 2013, he told Fox13 News: “The home run is to find a young juvenile girl who is ready to be rescued.”

He later told ABC’s “Dateline” that he aims to get victims “to the point where they can’t wait to get on the stand.”

Since 2013, Guyer has referred 10 cases to King County prosecutors. Of these, only one involved an adult trafficking victim: Angelica Campbell.

In response to questions from KUOW and The Seattle Times, Guyer wrote in an email: “These heinous crimes are taken very seriously and we work hard to investigate and seek justice for the victims. Unfortunately, in some cases the facts and evidence do not always lend themselves to successful prosecution.”

This is consistent with Seattle Police’s overall record. In the past nine years, the department referred to prosecutors just two cases that explicitly cite human trafficking, both declined for insufficient evidence. And just over 1% of all cases it opened for sex crimes have included the charge of human trafficking, the majority since 2017.

In addition, Seattle Police participated in at least six federal trafficking investigations for Washington state since 2015.

Prosecutors argue these numbers are low because the trafficking statute itself is cumbersome and, like using arrows in a quiver, it is easier to use different statutes to prosecute similar crimes, including knowingly selling another person for sex and profiting off the sex work of a minor.

Of this larger set of crimes, Seattle Police has referred a median of 10 cases a year between 2015 and 2021. The majority, just over 60% of Seattle Police’s referrals, involved crimes against children.

These numbers are striking for another reason. Washington considers itself a national leader in anti-trafficking, boasting the most stringent law in the country, and since 2002 has passed nearly 40 related laws.

Yet the state got off to such a slow start of holding criminals accountable for trafficking crimes that no charges were brought for four years. The state Attorney General’s Office intervened in 2008, finding, “the law wasn’t being used because victims of human trafficking were not being recognized as such.”

The Urban Institute estimated in 2007 that Seattle’s underground commercial sex industry economy more than doubled since the first law passed, to $112 million per year.

Most years, more than 200 cases are reported annually to the National Human Trafficking Hotline for Washington.

A state task force told the Legislature that trafficking is “rarely identified,” even by law enforcement, which often jails or charges trafficked individuals with prostitution and other crimes instead of recognizing their victimization.

By 2014, a state report found half of Washington jurisdictions had never investigated trafficking cases. Agencies didn’t understand “the problem of sex trafficking itself,” and many were unaware the laws existed, although training has since improved.

This is reflected in Seattle Police crime statistics. Since the attorney general first highlighted problems with under-identifying trafficking crimes, 3,600 cases were opened for prostitution, compared to 50 cited from human trafficking offenses.

G

uyer hadn’t spoken to Pearl in three years when she received a text in January 2021.

“I don’t know if you remember me,” Guyer wrote.

It was conspicuous timing. Over the last month, Angelica Campbell had detailed her experience to Guyer, and KUOW had published the first public account of alleged crimes committed by Simone, and included the story of yet another woman who said Simone harmed her, Amanda.

Guyer also had been made aware of at least three additional women involved with Simone, including one Simone had allegedly trafficked since she was 15, according to his own police notes.

Guyer arranged an interview with Pearl and King County prosecutor Ben Gauen, conducted over Zoom.

After that meeting, Gauen emailed Guyer and another detective with an urgent laundry list with 19 bullet points, including all prior reports, interviews with other victims and Simone, as well as Guyer’s text messages with Simone.

“Several of the items are things that can be produced ASAP,” Gauen wrote in an email obtained by KUOW and The Seattle Times. “I need everything,” Gauen added, underlining the sentence for emphasis.

This information would have strengthened the case, but the county prosecutor’s office said police never provided it. Guyer did not answer questions about why it was not part of the final case file.

In summer 2021, four years after Pearl reported her trafficking allegations against Simone, Guyer sent Campbell’s case to the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office for a second opinion.

The 228-page case file had no mention of rape, or of the allegations made by other women. Guyer recommended against charging Simone. Gauen agreed.

“Declining to bring a case should not be construed as saying that she’s not a victim,” Gauen said about Campbell. “Oftentimes, we believe people and there still, unfortunately, is insufficient evidence to make a charging decision.”

A

Seattle court declined Campbell’s domestic violence protective order, finding she and Simone were not in an eligible dating relationship. So, Campbell got an attorney and filed a civil suit.

The case, she said, is her last avenue for justice. If the women win, they could be awarded financial damages for pain and suffering, including post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as for lost wages and medical bills.

When Campbell moved to Seattle to work as an artist, she believed she would be starting a family and having kids with Simone. “I told the people I was close to that I was going to marry this really cool guy, but when I got off the plane, his whole personality had changed.”

Two years later, she still feels unsafe leaving home, and struggles to date or make friends, unsure who to trust. She has reported to police that she was followed by Simone, but they have said they can’t help her without a protective order in place.

The bite marks she told police Simone left on her shoulder during sex have disappeared. But she said she feels uncomfortable describing what happened to her, even to a therapist.

Learning about other women, though, like Pearl and Amanda, allowed her to unlock memories and helped her make sense of her own trauma. And she has started painting again.

In a recent acrylic painting she calls “The Big Bang,” she depicts a Black woman facing away from the viewer, a gun in her thong and her middle finger up.

It is based on a theory in physics, that all creation, beginning with the birth of the universe, has the capacity to regenerate.

Ashley Hiruko: 206-574-8007 or hiruko@kuow.org. Ashley Hiruko is an investigative reporter at KUOW.

Rebecca Moss: rmoss@seattletimes.com; on Twitter: @rebeccakmoss. Rebecca Moss is an investigative reporter at The Seattle Times.

Confidential support for survivors

If you have experienced sexual assault and need support, you can call the 24-hour National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline at 800-656-HOPE (800-656-4673). There is also an online chat option. Survivors in King County can call the King County Sexual Assault Resource Center’s 24-hour Resource Line at 888-99-VOICE (888-998-6423) or visit www.kcsarc.org/gethelp.