Similarities Between Boston, Seattle Priest Abuse Are ‘Striking’

When the Seattle Archdiocese released names of 77 abusive clergy last week, many Catholics heralded a new era of transparency.

But attorney Michael Pfau raised an eyebrow. He knew something that wasn’t noted in the press release – or the flurry of news stories that followed. A major trial for a notorious pedophile priest was scheduled for June, and Pfau was interviewing victims.

“Why did you release these names late on a Friday afternoon before a holiday weekend in January?” Pfau said he would ask Archbishop Peter Sartain. “Why isn’t the archbishop addressing this in person, taking questions as opposed to putting out a list?”

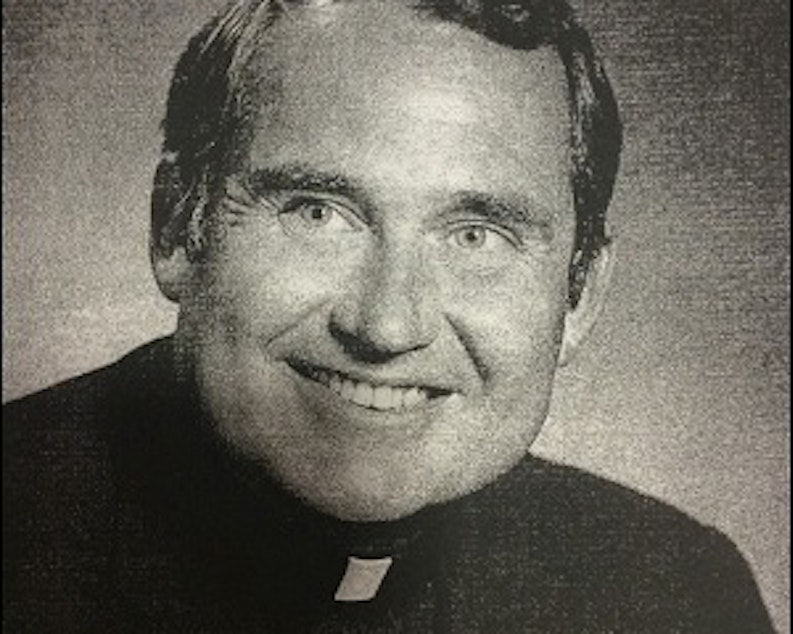

Pfau has represented hundreds of people in abused by clergy in Washington state. One of his current cases involves Fr. Michael Cody, who worked at St. Edward’s Seminary, St. Luke, Holy Family, St. James Cathedral, Sacred Heart in La Conner, St. Charles in Burlington and Assumption in Bellingham.

The church knew of accusations against Cody as early as 1962. In a March 19, 1962, letter to Archbishop Thomas Connelly, a psychiatrist said Cody had admitted to molesting eight girls age 12 or under and described him as exhibiting “sadistic tendencies toward boys.” Cody spent time in treatment, then returned to the archdiocese, where others within the church expressed concern as he moved from parish to parish, according to documents, where he continued to abuse kids.

Sponsored

In 1988, Cody admitted to abusing 20-40 girls and one boy, according to a psychological evaluation. But he remained in the clergy until he was dismissed in 2005.

He died in Nevada last year.

Seattle Archdiocese spokesman Greg Magnoni told KUOW’s Bill Radke the abuse isn’t just a Catholic problem.

“I wouldn’t call it systemic,” Magnoni said of the abuse. “It’s pretty much the same for that period of time as it was in the general population, around 4 percent” – he didn’t specify where he got this number – “but we hold ourselves to a higher standard. That’s not meant to offer an excuse for this tragedy.”

Pfau disagreed.

Sponsored

“It is very much a Catholic Church problem,” he said. “I would like to see this Archdiocese – and all the Catholic archdioceses – stop saying things like, ‘This is not a Catholic problem.’”

“Why are there thousands, if not tens of thousands, of Catholic victims?” Pfau said. “Part of the Catholic problem is they hid this, they kept it secret and they chose to avoid scandal. It is not slinging arrows as much as it is just fact.”

He said several factors make this uniquely Catholic. For example, he said, priests started at the seminary as adolescents, with limited access to women. Their sexual development was often stunted – and some may have been targets of sexual abuse as well.

Pfau noted the parallels between Boston and Seattle.

“The similarities between what happened in the Boston Archdiocese and Seattle Archdiocese are striking,” Pfau said. “They have roughly the same number of credibly accused priests, but Boston is a much larger Catholic community with a lot more priests. The same patterns of moving abusive priests from one parish to another without warning parents and parishioners.”

Sponsored

Last week’s press release included a hotline number for victims to call. Magnoni said the Archdiocese would conduct its own investigation. In some cases, the statute of limitations have run out, which means charges couldn’t be filed, or the priests involved have died.

“We don’t expect people to take our word for it,” he said. “Give us the opportunity to provide healing, to do the kind of work we’ve been doing consistently.”

But Mary Dispenza, director of Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, told Radke that victims should not call the Archdiocese.

“Victims need to go to the police, because what happened to them is a crime – not the church, because churches can’t police themselves,” Dispenza, a former nun said.

She said she wants to see priests and brothers out each other.

Sponsored

“Any clergy member who has committed a crime needs to be exposed, not protected,” she said.

“I would like the bishop to say to his priests – and I would like to see it in writing – ‘I encourage the priests under my care, should they know about the involvement of another priest, or even be concerned, I want to know.’ I’ve never seen that asked by the pope or archbishops.”

Dispenza was first abused by her parish priest when she was 7. She was watching a movie.

“I started walking up the center aisle. The priest was seated next to the projector – he beckoned me to sit on his lap. Why would I not? That is when he digitally raped me. In a way my world stopped. I can still imagine that movie fading out.”

She has tried to put the pieces back together, but she can’t remember what was playing.

Sponsored

“He walked me to the back of the parish hall,” Dispenza said. “I went into a small bathroom, and I washed my hands and in a way left half of me there. I went back to my mom and the women in the lunchroom and never told anyone. I buried that until age 52. From the second to the fourth grade that carried on in different ways.”