While spring rains help most of Washington, parts still under emergency drought

Although this spring has brought rain to parched Northwest landscapes, parts of Washington east of the Cascade Mountains will remain under an emergency drought declaration this summer.

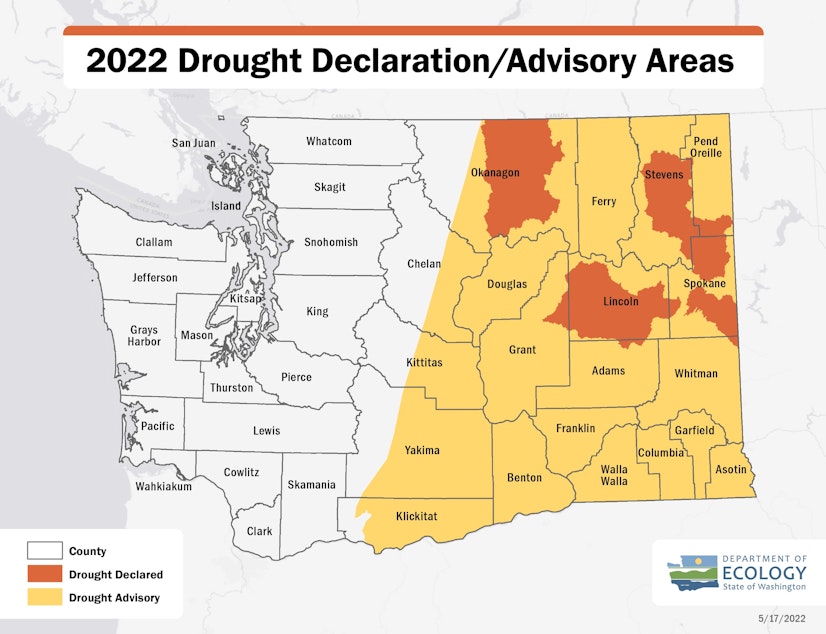

The five watersheds in parts of North Central and Eastern Washington include parts of Spokane, Lincoln, Grant, Adams, Whitman, Stevens, Okanogan, and Pend Oreille counties.

These drought-stricken areas could continue to see low soil moisture, dried out ponds, and earlier irrigation curtailments for people on the Colville River near Kettle Falls, and the Little Spokane River and Hangman Creek near Spokane.

In addition, Okanogan County in North Central Washington could see low water in storage reservoirs, including Salmon and Conconully lakes.

“This winter the reservoirs haven’t refilled like one would hope,” said Jeff Marti, drought coordinator with the Washington Department of Ecology.

Sponsored

Areas under emergency drought conditions have reported shallow groundwater levels below normal, Marti said, which can be a big concern for rural private well users who could run out of water.

“If you’ve had trouble in years past, your well has gone dry or your pump started sucking air, be really mindful this year of where your water levels are,” he said. “You might have to reduce your water use a little bit.”

Moreover, low levels of shallow groundwater could mean less water for livestock that depend on ponds and springs, such as around Upper Crab Creek in Lincoln County, where ponds remain dry after drought conditions last year, Marti said.

“You might have to haul water – bring water up to a tank or something, or move cattle to where water is, off the open range,” Marti said.

This declaration will allow the Department of Ecology to conduct emergency water rights transfers, which would allow junior water rights holders, who are typically the first to have to stop using water, to use water rights from senior water rights holders.

Sponsored

Water rights transfers can take years, Marti said. However, the streamlined emergency transfer process can happen within 15 days, he said.

“It gives some flexibility to water users,” Marti said.

The state Department of Ecology downgraded the rest of Central and Eastern Washington to a drought advisory status, which means people should be vigilant when using water, Marti said. All of the western third of the state no longer face drought conditions as of June 1.

Last spring marked the second-driest in Washington, followed by a record-breaking heatwave in June, after which 96% of the state fell under an emergency drought declaration.

The newest emergency drought declaration covers roughly 9% of Washington. With many fewer areas facing drought emergencies this year, Marti said Washington state is going in the right direction.

Sponsored

“This is nowhere near as severe as last year,” Marti said. “We just have a few areas where some of the watersheds haven’t gotten the precipitation that they need to build their way out of that deep precipitation deficit.”

So far this year, soil moisture conditions are better than last summer in southeastern Washington, Marti said. Recent spring rains have helped.

In addition, Marti said, wheat growers expect crops this year to bounce back after last year’s drought, he said.

In Oregon, Gov. Kate Brown declared a severe drought state of emergency for 15 counties in the eastern, central and southern parts of the state. Forecasts don’t predict any improvement. The U.S. Drought Monitor lists central Oregon in an exceptional drought, the highest level of risk.

Executive orders from Brown show the low snowpack and reservoir levels and low streamflow could lead to too little water for agriculture and drinking supplies. In addition, a lack of water could increase wildfire risks and shorten growing season, according to the executive orders.

Sponsored

In Idaho, the U.S. Drought Monitor shows the southern part of the state in moderate, severe or extreme drought. In April, the Idaho Department of Water Resources declared an emergency drought declaration for all 34 counties south of the Salmon River after the area saw below-normal snowpack and low water supply this spring. [Copyright 2022 Northwest News Network]