Upon Arrival: How refugees find their way in Seattle

For many refugees, the first year can feel like a race against the clock to set up a new life.

You get a little cash up front and a few months of help from a social worker.

Then, you’re mostly on your own.

We followed three refugee arrivals, from touchdown at Sea-Tac Airport to eight months into their lives here. Eight months, because that’s when refugees without families stop receiving small federal payments.

They are Osman Mohamed of Somalia.

Peiman Karimi and wife Neda Sharifi Khalafabadi of Iran.

And Tu Tu – his full name, because Burmese people don’t use last names.

Their stories are as different as the countries they come from, but they start with a similar thread – leaving despair behind and grasping for hope.

Osman's story

"I'm called Osman Mohamed. I'm just a refugee."

Osman fled Somalia to a refugee camp in Kenya, before arriving here on Dec. 8, 2015.

“I run from my country since back 1993. And I just came to Kenya for issues of security and protection.”

A scar behind Osman’s ear traces back to that time.

His mom refuses to tell him how it happened. But Osman knows it’s connected to the day his younger sister died. He says hostile men attacked their home. They raped and killed his sister and his aunt.

“While I came to U.S., I thought I stepped on the proudest step. I found peace, peace country. I love it. And absolutely I wish to get as soon as possible, to be a better life."

Somalis now make up one of the largest groups of refugee arrivals to the U.S. Seattle is home to the third largest population.

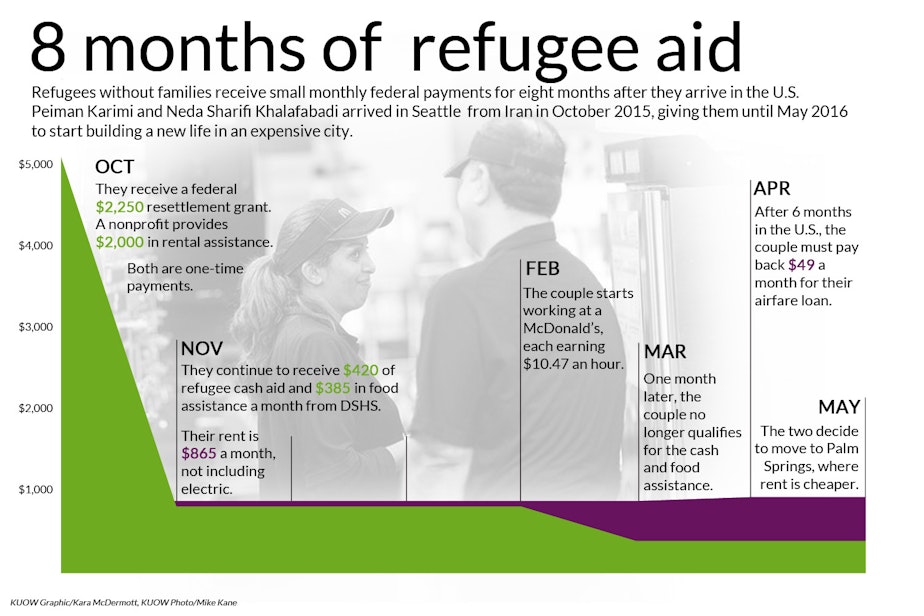

Neda and Peiman's story

Neda and Peiman left Iran four years ago

They went to Turkey first, which left them broke and broken-hearted. They arrived in Seattle Oct. 21, 2015.

They are close to 40 now. They feel young and open to new career paths. Seattle, with its robust economy and high minimum wage, is a draw for new refugees.

Since the Iranian revolution in 1979 and the subsequent shift to an Islamic government, more than 96,000 Iranian refugees have been resettled in the U.S., making it the eighth largest arrival group during that period. California is the top resettlement state; Washington ranks third.

In Iran, Neda trained as a pastry chef and worked in a bakery. She often gives a half-smile with a furrowed brow. Her family teases her that she worries a lot. Her nickname is “Neda Stress.”

Peiman has a sweep of dark hair and a playful laugh. He worked various trade jobs in Iran — electrician, tel-com technician, welding inspector.

“Everything for me is different and change,” he says. “Country change, language change, city change. Here now life is starting new.”

Tutu's story

Tu Tu lugs a bag off the carousel

He’s 20 years old – playful, smiling. With long bangs and torn jeans, he looks pretty American on his first day here, August 27, 2015.

But he barely speaks English, which terrifies him. How will he get by if he can’t communicate? It’s a fear he pushes aside. He’s not supposed to be a kid anymore.

Tu Tu’s cousin Sheltar is here to greet him after many years apart.

They cry, but they don’t hug. That’s the culture in Myanmar, formerly known as Burma.

In the past decade, Burmese refugees have topped the list of new arrivals to the U.S. It’s a relatively new community, finding its way here.

Tu Tu will live at Sheltar’s two-bedroom apartment in Kent. Her sister’s family also lives here. Tu tu brings the total to nine. He’ll sleep on a twin bed in the living room.

Tu tu fishes a picture frame from his backpack.

It’s his girlfriend from the refugee camp. The frame says, “Forever Love.”

He pulls a bible from his bag, then another, and another. There are at least four – in his native Karen and English, a language he’s eager to learn.

A social worker leaves Tu Tu a $20 bill. It’s for random expenses. He spends it in a few hours, on a phone card, to call his dad back in Thailand.

Getting by with a little help

When refugees arrive, they get small grants to help them get started. Here’s a typical budget for an individual:

Each refugee receives a one-time federal grant as welcome money, which ranges from $925-1,125. These funds are often used toward rent or household needs. Refugees without children also receive federal cash assistance for up to eight months, or until they find a job. Whichever comes first. The maximum monthly payment varies by state; in Washington it’s $332 per person.

Refugees who arrive as families with children will receive Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash grants. This benefit is available to refugees for up to five years.

They’ll also get a caseworker during their initial resettlement (for up to three months), who will help them navigate unfamiliar American systems – everything from learning to ride a bus to creating resumes.

The U.S. resettlement program steers refugees toward employment and self-sufficiency right away.

Various government programs help with job placement for up to five years. The Office of Refugee Resettlement, which tracks outcomes, provided a 2014 report to Congress that shows about half the refugees in its caseload found employment. But it’s not a complete picture, since some refugees find jobs through other avenues.The money and assistance programs help, but new realities set in quickly.

And for many, what they left behind still haunts them. It’s estimated about one in three refugees experience mental health issues due to violence, displacement and loss.

"On Friday there was killed a man here"

“Right here,” Osman says. “I saw it. I saw the man who’s been shooted. Take for the pistol up like this, pow pow.”

Osman had only been in this country four weeks when his family witnessed two separate shootings outside their apartment in Burien. The first is on a Friday; the next five days later.

“My kids they saw the blood, they saw the corpse,” he says. “They have been crying. They did not know what to be done.”

His daughters are 2, 4 and 5.

“They even told me that, ‘Dad, we are not going back to our apartment. We will be dead if we go there.’”

It’s a bitter irony.

“What I have run from in my country is because of a gun, and still I find the guns," he says.

They left Somalia because of discrimination.

“We are a people who are just a minority tribe, Barawa,” he says. “In Somalia, even some people when we are just passing them, they do like this.”

He pulls his shirt over his nose, as if to smother stench.

“They don’t like us. They make us like we are smelly.”

Osman’s childhood left him with nightmares. He hopes to spare his daughters that pain.

Neda and Peiman don't say why they left Iran

Did something bad happen to them?

"Yes," Peiman says. "Not me. To Neda.”

Neda says she doesn’t feel comfortable to talk about it because it’s going to bring everything back to her again. All she says is her case is religious. The rest is confidential.

The U.S. defines a refugee as someone with a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country. Iran is a majority Muslim country. Religious minorities face discrimination, surveillance and arrest.

Peiman and Neda are Christian.

Tu Tu spent most his life in a refugee camp

His family is Karen, an ethnic minority in Myanmar. For decades, military forces have attacked and burned ethnic villages. More than a million people have been displaced, including Tu Tu’s family.

“While we moved to camp I carried one chicken,” he says.

It is a child’s memory - he was about 5.

“It was an attack. They tried to kill all the Karen people and then my grandmother had to carry me out."

His grandmother later told him many people died on the way to Thailand. His brother and sister got sick and died young. His mother left after he was born.

In Thailand, Tu Tu settled into a routine life with his father and grandmother. But it was like living in a cage. And as he got older, his dad pushed him to leave and look for opportunity. Tu Tu wanted to stay. But he followed his dad’s wishes.

Starting a new life — that’s what they all want to do. But for each of them, that means something different. Tu Tu’s main goal is to learn English. It’s his dream to be an interpreter someday.

For Tu Tu’s first eight months here, he gets government aid of $320 a month – as long as he’s looking for work. It’s not much, but it buys him a little cushion of time. And he wants to use it to learn English.

It’s his cousin Sheltar’s advice. She and her husband never had this cushion; they had to pay the rent.

And she says it made her feel bad, that maybe her co-workers didn’t like her because she couldn’t understand English.

Tu Tu starts taking English classes right away. Six months in, he approaches it like a full-time job.

He takes the bus to class, about an hour each way, four nights a week.

He arrives early, sits in the front and confidently calls out answers. He makes his classmates laugh.

His ambition is paying off. He can have conversations in English.

But the odds are against him when it comes to English fluency.

In Census surveys, roughly one out of five Burmese people in the U.S. say they speak English well. The rest will finds their worlds limited in many ways, especially in the job market. About 30 percent live in poverty; a rate nearly double the general population.

"I still remember my parents"

For Osman, starting a new life is complicated. He can’t leave his old life behind. His parents and 10 younger siblings are still in the refugee camp in Kenya. An older brother went missing a few years back. His father had a stroke last year and is now partially paralyzed. The refugee camp may shut down. He doesn’t know what will happen to them.

“I’m not sleeping well. Too much worry. Too much thinking back with my parents, what’s going on with them, you know?

“I hoped I would forget for the past persecution what I’ve gone past in my country and the refugee camp.”

After the shootings at their Burien apartment, Osman’s family refused to stay. They crashed with refugee friends for a few weeks, then settled in to a new apartment in Federal Way.

On a relaxed Saturday at home, Osman’s mother, Asha, calls from the refugee camp. The girls erupt with joy – this grandmother helped raise them until now.

Asha tells Osman that his father is having more health issues.

“There’s no help at all. I’m here. Tell me what can I do?” Osman cries.

His daughter touches her small hand to his face, comforting him.

"I'm going to feel your tummy, OK?"

Neda is pregnant. This wasn’t the plan, but the baby lights her and Peiman with joy.

It also makes getting a job feel more urgent.

Their first months did not exactly go as planned. Rent is higher than expected. They pay $865 a month for their one-bedroom apartment in Kent.

Peiman was stressed, but tried to keep up Neda’s spirits. This journey had been hard on her. She cried a lot.

Then, a couple weeks back, they turned a major corner.

They both landed their first job at one of the most all-American places around – McDonald’s.

It’s no coincidence they found this job. Lots of Iranians work here, says their manager, Mosh Zari.

“I have about 20 of them working for me,” Zari says.

All from Iran?

“All from Iran. Yes.”

Zari is also Iranian.

These jobs are a humbling step down for Neda and Peiman. Zari sees that a lot.

“I’ve had people that were engineers back home, for instance, but for now they had to work and have an income.”

Peiman tends the fryer. Neda assembles sandwiches.

Neda and Peiman earn about $10 an hour. Data show a refugee’s income tends to steadily increase over time. But it’s gotten tougher. And today’s refugees are not making the same gains as those who arrived in the 1980s and 1990s.

A recent study from the Migration Policy Institute suggests several reasons for this lag: the recent recession, an influx of new refugee groups with low education and minimal levels of support for them upon arrival.

Where are they now?

The Seattle-area ends up being too expensive for Neda and Peiman, so they decide to try their luck in Palm Springs, where Peiman has more family and there's a much larger Iranian-American community nearby. Their new rent will save them a couple hundred dollars a month.

"I ask God to prepare everything, clear path for us, let me reach goal and dream," Peiman says. "Of course we're not there yet, but I see the path is kind of clear and I’m moving toward that."

It’s common for new refugees to relocate. Officially, this is called secondary migration. And some experts say it’s an overlooked challenge in the resettlement process. Because people move around, but their support services don’t.

Tu Tu has turned 21.

He’s not in English class anymore. His cousin helped him land a job at an electronics manufacturer in Redmond. He solders together parts for $13 an hour.

His conversations skills are expanding – “Hasta mañana and salud and gracias,” he says laughing.

Tu Tu stuck with English classes for the first eight months, as planned. But now, there’s no more time. His relatives have worked similar factory jobs for years. And perhaps he will, too.

Compared to all refugees in the U.S., Burmese are among the most likely to stay in low-wage jobs due to low levels of education. Nearly half drop out of high school. (Odds are later generations will find greater success and stability.)

Tu tu seems proud of his job. He helps pay the rent, he’s paying off the travel loan for his flight to the U.S. And he sent $500 to his father back in Thailand.

“My grandma is sick,” he says. “They need help and they need money, so I sent money.”

He says life here is good. It’s not what he expected. But he’s not really sure what he expected.

He misses family back home and familiar surroundings. And sometimes, he’ll ask a friend to drive him to a nearby park.

“In the mountains,” Tu Tu says, “so I can hear the sound of the river and birds.”

It sounds like the mountain village where he grew up, thousands of miles away. And it makes him happy.

Five months after Osman arrived, he's got a job

It's as a dishwasher at a bakery in Seattle. It’s a two hour commute each way by bus and light rail.

A nonprofit is helping with their rent for a few months. But he’s not sure how he’ll pay some other expenses, including an $800 hospital bill – a car hit him in the crosswalk and sped off.

Osman has had more than his share of obstacles and sometimes he just breaks down crying. He says it scares him, makes him feel dizzy. He’ll just be crossing the street, and it hits him. His wife says she’s never seen him cry like this.

“Sincerely, if I told you the truth, you cannot achieve or reach your aim if you don’t struggle. So now, I’m struggling.”

And he says he OK with the struggle. Because here, there’s also hope that he can heal and move forward. And that’s something he hasn’t felt in a long time.

To help refugees in your community, visit https://www.whitehouse.gov/aidrefugees