This pioneer worked the Underground Railroad — and founded Seattle's Black Central District

In the early days, they called him Big Bill the Cook.

He was William Grose, a Seattle pioneer who rented a lunch counter at Reuben Lowe’s saloon in Pioneer Square.

He was a force the moment he stepped off the mail boat in 1859 or thereabouts. He stood 6 foot 4 and had lived many lives: cook in the Navy, gold miner in California, international negotiator for the Underground Railroad. He was said to be the second Black man to arrive in Seattle.

By all accounts, he was popular and deeply respected across color lines. In time, he’d become one of the wealthiest men in Seattle. He saved money to build a three-story hotel on Yesler Wharf, and bought 12 acres in the Madison Valley, establishing a foothold for the African-American community in part of what is now the Central Area.

But Grose, unlike his pioneer peers at the time — Denny, Greenwood, Phinney, Yesler, McGilvra — has been overlooked by Seattle history. The city honors its early settlers by naming streets, neighborhoods and schools after them; Grose has a pocket park. Even the main street that cuts through the area he launched into a vibrant cultural center, Madison, bears the name of a slave-owning president who died before Seattle was established as a city.

“He is overlooked,” said Esther Mumford, a founding member of the Black Heritage Society and author of Seattle’s Black Victorians.

Sponsored

Mumford said the Groses were a light in the community. “Well known, well respected. People thought they were people you could seek advice from. And because of his gigantic size — it would have been hard to miss him.”

(By his own boasting, Grose was the largest man in Washington state. In addition to his height, he claimed to weigh 428 pounds. A Seattle Post-Intelligencer newspaper blurb noted that Grose challenged another man for the title.)

William Grose was born in 1835 in Washington City (later folded into the District of Columbia), to a free man who worked in restaurants. The nation’s capitol presented a paradox: the city had a thriving slave trade, but free people outnumbered the enslaved two to one.

Grose did not learn to read or write, which historian Esther Mumford believes may have been because white people were imprisoned, and often had to pay fines, for teaching Black to people to read and write.

Sponsored

At 15, Grose joined the Navy.

“A cook’s boy, you can’t get any lower than that, that’s his rank,” Mumford said, adding that he likely peeled potatoes across the Pacific.

Newspaper articles from the time tell of Grose jumping overboard to save a shipmate. When he later sought recompense for an injury to his right leg, the Navy denied him.

After leaving the Navy, Grose headed for the gold fields of California. He was a tall, muscular young man, Mumford said, and acted as a protector to other miners.

In California, Grose was active in the Underground Railroad. He spoke Spanish — learned during his travels with the Navy to Latin America, or in the California gold fields — and went to Panama to negotiate with the government, asking that they not send back enslaved people who had escaped. Accounts from the time indicate he was successful.

Sponsored

Grose moved to British Columbia and worked on a mail boat that stopped in Seattle — that’s when he met Gov. Isaac Stevens of Washington Territory. Stevens was 5-foot-3, more than a foot shorter than Grose, with a reputation for being brutal toward Native Americans at the time that he met Grose. Still, the men apparently hit it off.

The story goes that Stevens lost a watch, and Grose found it and returned it. Stevens liked Grose so much that he convinced Grose to move to Seattle. Grose agreed.

In the years that followed, Grose married his wife Sarah Grose, later known as Granny Grose. They had a son named George and a daughter named Rebecca.

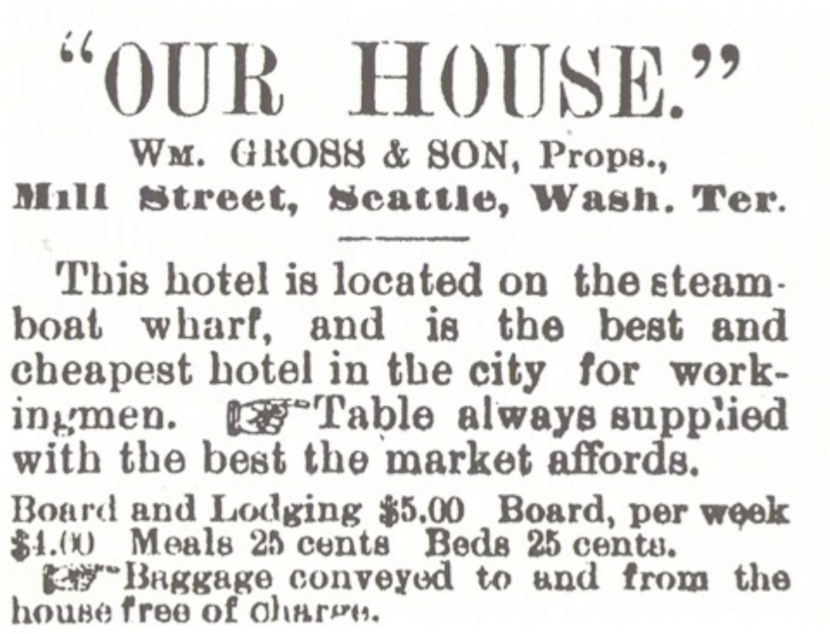

In 1876, Grose used his saving from the lunch counter to build a restaurant that would become the city’s second largest hotel, “Our House.”

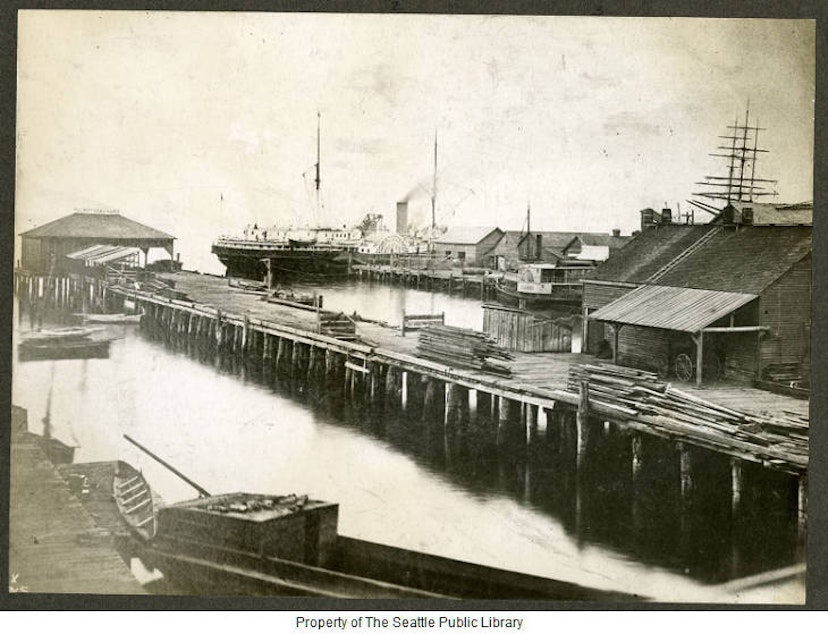

Three stories high, it was located at Yesler Way and First Avenue. Grose lived at the back of the restaurant, according to directory information at the time.

Sponsored

The hotel opened in 1883. “Boarding on the most reasonable terms,” reads an ad for Our House in the Seattle P-I. “Meals at all hours.”

Meals cost 25 cents, as did beds, but Grose provided even for the penniless. A future mayor of Seattle would later tell of showing up to Seattle without a dime in his pocket.

“He went to Bill Grose’s restaurant, and he told him that his credit was good there until he could repay him,” Mumford said.

Grose was thrifty, however. Mumford relayed a story from a pioneer businessman who said he once overheard Grose planning the next meal.

“Scrape all the dishes into one pot,” Grose reportedly said. “We’ll have hash.”

Sponsored

At Our House, people could rent safety deposit boxes. The Seattle P-I archives include stories of drunken strangers stumbling into their beds on the top floor. A few of these men died in their sleep, with Grose and his staff to clean up.

In 1882, Grose bought 12 acres in Madison Valley from Henry Yesler for $1,000 in gold coin. (A University of Washington sociologist wrote in 1944 that Grose was given the land in repayment for a debt, but Mumford, and newspaper archives, and county records, show this is inaccurate.)

This was not the Madison Valley of today, dense with houses, expensive stores and Starbucks. The area was wooded, with more bears than people.

Mumford interviewed a woodseller who moved to Madison Street in 1910 with his family.

“It would take so many teams of horses to pull wood from Lake Washington up that hill, because it wasn’t paved,” she said. “There was no electricity. There was no sewage. This was turn of the century.”

Grose built a modest farmhouse on his acreage, and raised poultry and grew fruits and vegetables for Our House. He also sold parcels of land to other Black families. But he didn’t move to his farmhouse until after the Great Fire of 1889.

The great fire wiped out Pioneer Square and the Seattle waterfront, including Our House. Grose had sold his hotel for $5,000 days before the fire. By several accounts, he found the buyers and returned the full amount to them.

“I think he was courteous, and a man of integrity,” Mumford said. “Kind, generous, but he never stopped fighting.”

The fire marks a before and after time for Grose, who appears to have entered retirement and assumed an elder statesman role in the city, and also for Seattle and Washington state.

Five months after the fire, Washington became a state — and more racist, as outsiders moved in.

“A lot of them had come from Confederate states, and that was not helpful to Black people’s existence,” Mumford said.

A new journalist in town wasn’t having any of this. Horace Cayton, born to an enslaved man and a white plantation owner’s daughter, moved to Seattle in the 1890s. He launched his own newspapers, and was also the first Black editor at the Seattle P-I.

“Cayton made Black people very nervous,” Mumford said. “He was taking on white people in an aggressive fashion, rather than more subtly meeting half-way.”

In the Long Old Road, Horace Cayton’s son, a sociologist also named Horace, explained his father’s thinking.

“Race prejudice was spreading in Seattle at that time, and many restaurants that had previously served Negroes now began to refuse them service,” he wrote. The Strand Theater on Second Avenue insisted that Black people sit in the balcony.

“Things are changing here and not for the better,” Horace Cayton recalled his father telling him in Long Old Road. “I can remember when it didn’t matter what color you were. You could go any place and work most any place. But it’s different now.”

Cayton was unapologetic in his writing, and the established Black community in Seattle worried he was going too far.

In a letter to the editor in the Seattle P-I, Grose and others threatened to remove support from the Seattle Standard, a Black newspaper.

“Unless proper apology be made by its present editor Mr. H. R. Cayton, for its uncalled for attacks lately made, we withdraw our names from the subscriptions list until the management is changed,” reads the letter.

It continued: “These resolutions are not intended to strike at Negro journalism, and we pledge our support to the Standard when the proper apology is made, or when the management is changed.”

Their plea did nothing to soften Cayton, who became sharper and wittier as the years went on. In 1901, Cayton mocked Police Chief William Meredith, and the chief had him arrested.

Cayton had written:

Chief of Police Meredith proposes to run quack doctors out of business, which perhaps is not a bad idea, but we suggest that while he is running quack doctors out of business, that he likewise run grafting policemen out of business; then perhaps the city of Seattle would be rid of Meredith himself.

After being released, Cayton republished the passage that had gotten him arrested.

In 1898, William Grose died at the age of 63. The manner of death was “dropsy,” according to his obituary in the Seattle P-I, a term that meant swelling or heart disease.

That obituary doesn’t sit well with historian Esther Mumford. The piece takes a mocking tone and begins with Grose’s size, and how his casket was too large to bring through the front doors of his home. “By the time he died, people looked at Black people very differently,” Mumford said.

Mumford said she hopes to write a children’s book about Grose someday — and to see him written about in textbooks, so that African American boys in particular may learn about him.

She would also like to see his house, which still stands, designated as a historic site. The modest farmhouse is the oldest continuously occupied building by a Black person in Washington state, she said.

“I would like for people to understand that if you’re poor, or a Black person from an average home, people make these judgments about you, but you can still succeed,” Mumford said.