Here's why rich Seattle schools can afford extra teachers and fancy gadgets

- What every school has fundraised and which schools can afford to buy teachers

- Some parent teacher groups hire staff directly, without the district's involvement

- A Seattle principal said some staff hired by PTAs are not vetted

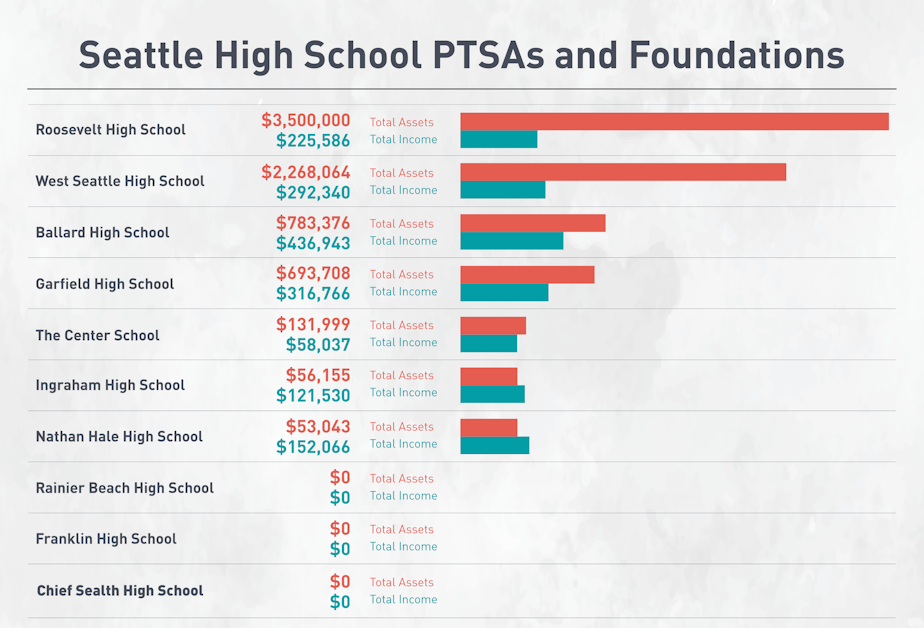

Roosevelt High School in north Seattle is a fundraising machine.

The school’s fundraising groups have $3.5 million in assets. Its foundation has paid for MacBooks, microscopes, professional cameras — and a bear costume that cost $1,250.

Half an hour south at Rainier Beach High School, the parent teacher association has $0 in savings. That’s not a typo: zero dollars.

The ethics of PTA fundraising

KUOW’s Isolde Raftery wrote a piece about vast disparities in Seattle PTA funding. Why don’t parents try to lift all boats? Tom Halverson, director of the Masters in Education Policy at the University of Washington’s College of Ed, calls this the margin of perceived competitive advantage – the schoolchild version of “all animals are equal, but some are more equal than others.”

What little they raise during the year “goes to pay for lunches for staff on teacher appreciation days," teacher Colin Pierce said.

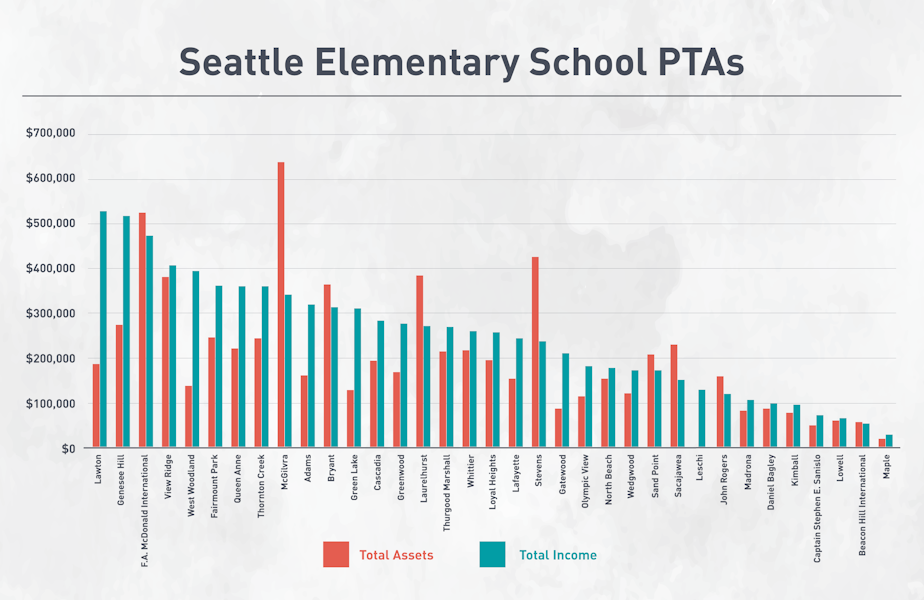

The contrast between rich and poor schools is stark in Seattle, where PTAs operate as independent nonprofits attached to individual schools. Their money is difficult to track, as is their influence, but the broad strokes are clear. The 10 elementary schools with the most PTA money have $4.5 million in assets combined; the bottom 10 have almost nothing. Some schools don't even have parent groups.

PTA money makes public schools more competitive with private schools because they pay for big ticket items, like extra teachers to keep classes small.

There are rumblings to pool PTA money district-wide so low-income students benefit. But others worry such a plan could backfire.

'Elephant in the room'

PTAs are good for schools and for students — research shows this. Involved parents lead to higher test scores and happier teachers. But reliance on PTA money means that some Seattle schools have tutors and smaller class sizes — simply because the parents there are wealthy.

Sponsored

Some parents at rich schools say they shouldn't be blamed for wanting the best for their kids.

Vivian van Gelder, whose children attend Montlake Elementary, a small school amid million-dollar homes, is part of a group called FACES (Families and Communities for Equity in Schools) which supports pooling PTA money.

"I don’t think it’s productive to demonize people for doing what society has been telling them to do — which is put ourselves and our children first," van Gelder said.

But it's tricky, she said. "How do you get people to move past that?"

"It’s not just unfair to some schools," she continued. "It’s unfair to schools with more black and brown kids. That’s the elephant in the room."

Indeed, 9 of the 10 schools with the highest percentage of black students have little to nothing in PTA money.

The exception is Leschi Elementary, a school in Seattle’s Central District, the city’s historic black neighborhood, where wealthy white families have been moving in.

At Montlake, the PTA gave 5 percent of its revenue last year to Lowell Elementary, where 20 percent of the students are homeless. Whittier, Queen Anne, North Beach and Green Lake elementary PTAs also gave money to poorer schools.

What each Seattle PTA has in assets and income

- Green: more than $250,000 in assets

- Yellow: $50,000 to $249,999 in assets

- Red: Too little to file a tax return

Knowing PTA money is available gives teachers peace of mind.

Arlene Harrington, now retired, taught at Highland Park in West Seattle, where 71 percent of the students come from low income homes, and later at Green Lake Elementary.

Harrington recalled the ease of working at a school with PTA money.

At Green Lake, “the teachers feel more supported, because they know they have more money for their classrooms, items of choice," Harrington said. “If I needed something, I could put in for a grant knowing the PTA could help me.”

Harrington said she adored her students at Highland Park, but she didn't want to ask parents for even $2. There, she said, teachers would buy materials with their own money.

But PTAs buy more than just school supplies, of course; they buy staff. This practice dates back to World War II, when moms went to work, and PTAs arranged for daycare. In the 1950s, PTAs organized kindergarten co-ops, and then pushed the state to pay for kindergarten.

Today, though, just the wealthiest schools get those extra staff.

Whittier Elementary in Ballard pays for a part-time assistant principal. McDonald Elementary in Wallingford pays for three assistants for its language immersion program. Laurelhurst Elementary throws a lavish auction (including $100 raffle tickets, Mexico getaway and a vasectomy by a physician who calls himself Dr. Snip) to cover a music teacher and teaching specialists.

Paying for teachers and staff

- Yellow: PTA pays for staff

- Gray: No extra staff

These hires usually go through the school district, but not always.

“PTAs do this to have more control over the hire, like, they can hire a mom they know,” said a Seattle principal who spoke on condition of anonymity. The principal worried about blowback from the district and parents. “But parents are not often properly trained to work with kids.”

The principal said unqualified parents have worked with students in special education, and that someone hired to work hourly in the kitchen was not paying taxes and did not belong to a union. The principal said liability was a concern.

“They’re not vetted,” the principal said. Someone brought in by the PTA, the principal continued, whether hire or a volunteer, may not have the right experience to work with certain kids, and the district doesn't know.

“That’s the biggest problem," the principal said. "You don’t know who is working with the kids.”

PTA funding

The Week in Review, hosted by KUOW's Bill Radke, discusses PTA funding in Seattle.

Chandra Hampson, president of the Seattle Council PTSA, said some of these hires fly under district radar.

“The quality of the school should not be determined by the wealth in the neighborhood,” Hampson said. “There are schools where the community has come together and put in great programs, but it’s a massive, uphill battle.”

Hampson continued: “This money is not being spent in the way we intended. That’s a crazy way for a small group of people to have impact.”

Tim Robinson, spokesperson for Seattle Public Schools, said there are no informal arrangements to pay teachers and other staff.

When asked to explain why Laurelhurst Elementary's budget for last year didn't match the district's accounting of staff, Robinson suggested an error had been made on the PTA end.

"If it is discovered that compliance is not being met, Seattle Public Schools will work with the group to bring them into compliance,” Robinson said by email.

But van Gelder and others with direct knowledge of how PTAs work said there is no doubt that "informal" staffing happens across the district, said van Gelder, whose children attend Montlake Elementary.

Van Gelder said PTAs have been asked to put money into the school’s “self-help” fund, which has more flexibility. Grant managers at the district have shuffled money into the self-help fund as well, she said.

Van Gelder said she knows of a school PTA that had a staffing budget of more than $300,000. That would have triggered the requirement for full school board approval, so the district advised the group to move some money into the self-help fund.

Robinson, the district spokesperson, said it is not unusual to pay for staff out of the self-help fund.

He shared an email thread in which a district administrator advised a treasurer at Thornton Creek Elementary on hiring tutors (pay: $15.45 an hour).

The administrator presented two hiring options: Through the school district or with the PTA and school, in which case, the tutors would need their own business license and insurance.

Schools that pool

Parents at schools with big PTAs have defended their robust coffers by pointing out that low income schools get hundreds of thousands in federal money.

That’s accurate, but "they’re funds that compensate for some kind of disability, or inequity,” van Gelder said. “They are funds to level the playing field.”

Pierce, the Rainier Beach High teacher, surmises that the district doesn’t interfere with PTAs for fear of losing families to private schools.

“So many of the structures that we see in a number of urban districts are to prevent white flight,” Pierce said. “The parents donated a lot of money to make their child’s public school on par with private schools.”

Jill Geary of the Seattle School Board told KUOW last year that she worried sharing PTA money could backfire — and that parents might not vote for a school levy. There are two levies on the November ballot.

Nearby school districts Bellevue and Lake Washington don’t allow individual PTAs to pay for teachers. A foundation solicits donations instead.

Palo Alto, which launched a foundation for its school district in 2005, still gets pushback, however.

“They want to designate to their schools,” said Linda Lyon, executive director of the Palo Alto foundation. “But there are also big donors who believe in sharing the money across the district.”

Here in Seattle, there is a sense among some PTA parents that now is the time for major change.

This month, the Seattle PTSA, led by Chandra Hampson, passed a resolution to focus on equity. How money is spent is central to that resolution, Hampson said: “You don’t expose the inequities until you pull back the PTA funding.”