The race for the coronavirus vaccine in Seattle, and the people behind it

We feature three people on the frontlines of developing a coronavirus vaccine.

I

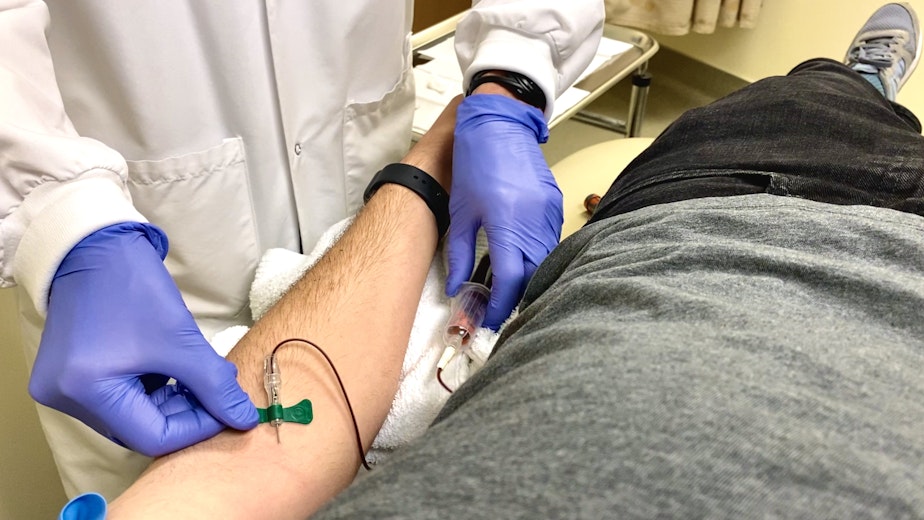

an Haydon is a science writer at the University of Washington. He’s also a vaccine volunteer. Haydon got his first shot of the first Covid-19 vaccine to be tested on humans earlier this month.

This vaccine is being developed by a Boston-based company called Moderna, using messenger RNA.

It’s different from regular vaccines you're familiar with, like the ones for the seasonal flu. Those inject you with a bit of dead virus or live virus that’s been weakened so it doesn’t hurt you. A messenger RNA vaccine instead instructs your body’s cells to make a protein – a little bit of the coronavirus – which, in turn, tricks your body into reacting and making antibodies.

Haydon is one of 45 healthy people who volunteered to make sure this new vaccine – if it works – will be safe for everyone. The only problem he’s had so far is a sore arm for about 12 hours.

Ian Haydon's vaccine audio diary

Ian Haydon describes getting his first dose of the first coronavirus vaccine to be tested on humans

Haydon said nothing more serious is likely to go wrong. In extremely rare cases, a vaccine that is being tested could cause problems.

Safety is one reason why clinical trials are needed, and why it takes so long to develop a new vaccine. But if it works, this vaccine is quick to make. So it could be the first Covid-19 vaccine available.

Sponsored

That’s why Haydon was excited to volunteer for the clinical trial, and why the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is backing it.

L

ynda Stuart directs vaccine development at the Gates Foundation, which is spending hundreds of millions of dollars on its coronavirus vaccine efforts.

She compared the urgency the world now faces to a seemingly impossible form of gardening.

“It’s a bit like having a plant that you really desperately want to grow faster than it probably naturally can,” Stuart said.

Sponsored

The Gates Foundation is backing multiple efforts to make a vaccine, because not all will succeed, Stuart said. So the foundation is several that it hopes will work.

“Although there are hundreds of efforts out there, there are probably only 10 or 20 that are going to be fast enough and scalable enough to be impactful, especially where we're sitting in this global pandemic situation,” she said.

Vaccine development is only part of the challenge. Vaccines then need to be made and that's another big effort. To make sure that happens as quickly as possible, the foundation and its partners plan to build manufacturing facilities in advance.

Covid-19 also presents an entirely new kind of global vaccine challenge.

Sponsored

“I think we will come up with a vaccine. The question is if we can come up with enough doses to protect the entire planet,” Stuart said.

The world needs billions of doses. Stuart said for that, the world also needs two or three vaccines to be successful in part because there probably won’t be enough materials to manufacture enough of any one vaccine.

The needed materials range from "the biological basics like nucleotides which are the building blocks of mRNA vaccines." to other "more mundane things" like the materials needed to make the glass vials that hold vaccines.

"The good news is I we all see this as a humanitarian crisis and everybody's very strongly motivated to work together to find a solution," Stuart said.

N

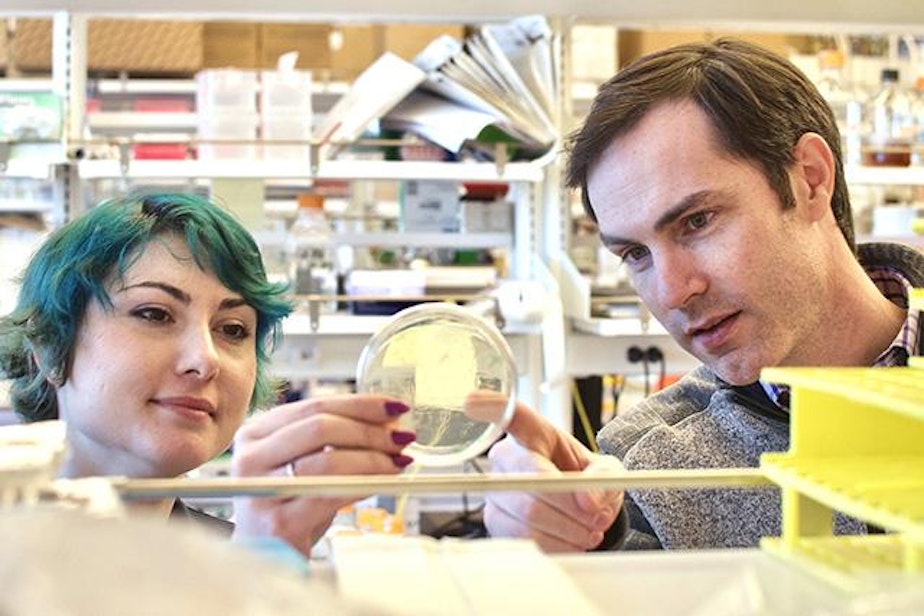

eil King is working on a cutting-edge vaccine backed by the Gates Foundation. He's a scientist at the Institute for Protein Design at the University of Washington, which has shifted all of its attention to the coronavirus, “in a way that we never had before.”

His lab is developing a “nanoparticle” vaccine. If it works, it would be possible to produce lots of it very cheaply. Lynda Stuart at the Gates Foundation said that will be especially important for people in the developing world where social distancing may not be an option.

King said this new nanoparticle vaccine is expected to trigger a strong immune response, which means a much smaller dose would protect people against the virus. That also means manufacturers can make a lot more of the vaccine using the same amount of raw materials.

“That could be a huge advantage” King said.

Will there ever be a nanoparticle coronavirus vaccine?

“I don’t know. We’re working very hard on it,” King said. “The thing to remember is vaccines have to be exceptionally, perfectly, beautifully safe, because you’re administering vaccines to lots and lots of otherwise healthy people.”

For that reason, developing a vaccine of this type by winter 2022 would be “remarkably fast.”

But like Stuart at the Gates Foundation, King said people should remain optimistic that vaccines will eventually help save the day.

“Human beings are really good at solving problems,” King said.