Seattle looks at new ‘poverty defense’ for misdemeanors

The Seattle City Council is preparing to discuss changes to its criminal code that, if enacted, would make Seattle the first city in the nation to excuse misdemeanor offenses linked to poverty or, potentially, addiction and mental health crises.

Earlier this fall, Councilmember Lisa Herbold proposed changes that could allow people to be found not liable for misdemeanors like theft, trespass and assault if their offense could be linked to poverty or a behavioral health disorder.

The Council decided to postpone the discussion until the budget was passed on November 23. A briefing is now scheduled in Herbold’s Public Safety Committee Tuesday, December 8.

Anita Khandelwal is King County’s Director of Public Defense. She helped develop model legislation in what she said is an attempt to live up to Seattle’s values.

“In a situation where you took that sandwich because you were hungry and you were trying to meet your basic need of satisfying your hunger; we as the community will know that we should not punish that. That conduct is excused,” she said.

Her proposal excluded misdemeanors related to impaired driving and domestic violence.

Sponsored

The city's proposed legislation isn’t even written yet, but it’s generated a lot of discussion. Former Seattle City Councilmember Tim Burgess has publicly opposed the effort.

“It sends this powerful signal that as city government, we don’t really care about this type of criminal behavior in our city,” he said.

Burgess argues that the new defense would come at the expense of store owners and others impacted by these crimes.

“It leans on the scales heavily in favor of certain individuals based on status, and it says to others, ‘you don’t matter,’” he said, adding that it amounts to “a defense lawyer’s dream.”

Seattle City Attorney Pete Holmes said he welcomes the upcoming discussion, but these changes aren’t necessary right now, because his office already avoids prosecuting “survival” crimes.

Sponsored

“Good prosecutors don’t take any satisfaction in prosecuting that type of offense,” he said.

Instead, Holmes said they seek to send people to diversion programs that provide needed services and avoid a criminal conviction.

Holmes said he shares the proposal's goal of moving beyond the reliance on police and prosecution. But he said there needs to be help available for the offenders and those that they’ve harmed.

“I think it’s running the risk that we excuse these crimes, we don’t couple it with the resources that are needed to make sure the behavior is addressed -- and then the community is left frustrated,” he said.

In an Oct. 30 letter, Holmes said if the City Council does move forward, they should split the proposal apart and focus initially on creating a poverty defense to nonviolent crimes like theft and trespass. That approach appears to have prevailed; the council’s initial briefing is focused on a defense for crimes committed to meet “an immediate basic need.”

Sponsored

Holmes said violent crimes -- even as a result of a behavioral health crisis – should be considered separately, with more supervision from judges to direct people to treatment and other support services.

“Random attacks on strangers are simply unacceptable,” he said. “We have to address that.”

Anita Khandelwal said the “poverty defense” isn’t meant to ignore the needs of businesses and others harmed by these offenses. She said the current system doesn’t provide them redress either, and it does more harm to offenders.

“It’s meeting nobody’s needs,” she said. “This is not that we don’t care about the business community or about people who have experienced harm. It is that we know that this process – this processing of human beings through the system – is harmful to our clients and again very racially disproportionate, and also not getting business owners what they need either.”

Khandelwal said Seattle should follow King County’s example in creating a public fund for restitution, so victims of theft can be compensated even if the offender can’t pay them.

Sponsored

At a teach-in recently, law professor Angélica Cházaro with Decriminalize Seattle called the poverty defense “the unfinished business of the 'defund SPD' movement,” and pledged to support the changes.

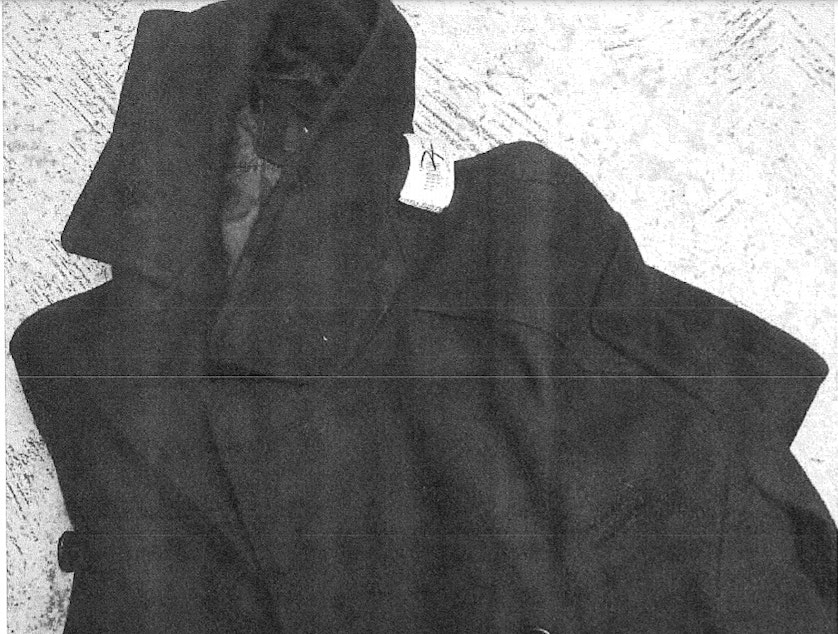

“Was a person in Goodwill stealing a coat because they don’t have a winter coat because they’re poor? Well, that seems very relevant, they probably shouldn’t face prosecution for that,” Cházaro said.

Khandelwal notes that a theft case against a man who stole a coat from Goodwill did go to trial this year in Seattle.

Councilmember Herbold chairs the Public Safety Committee which has scheduled a briefing Tuesday on “the concept of amending the Seattle Municipal Code to add a defense against prosecution of misdemeanors on the basis that an individual committed a crime to meet an immediate basic need.” Briefing documents say the Council would need to define whether the new affirmative defense applies only to someone meeting immediate basic needs, like stealing a sandwich in order to eat, or to items that are stolen for resale “so the defendant can pay rent.” Herbold says her committee will continue its work on the proposal in January.